[Photo story] Wang Lengzhai and the Lugou Bridge incident

Photo collector Zou Dehuai shares his collection of photos from the Marco Polo Bridge or Lugou Bridge incident, remembering the countless innocent lives that were lost under the hands of the Japanese army.

(All photographs courtesy of Zou Dehuai.)

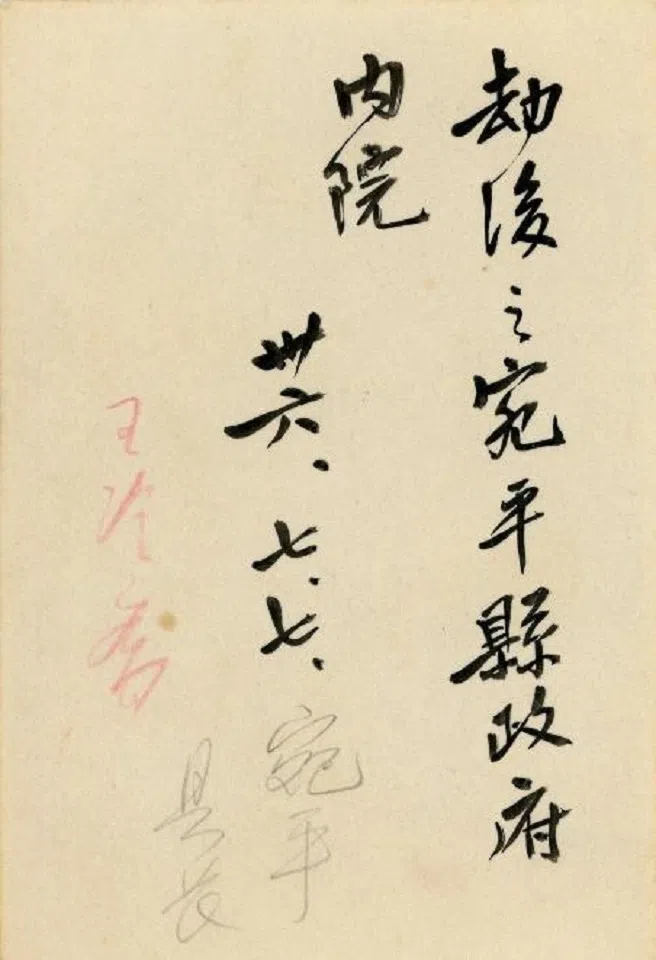

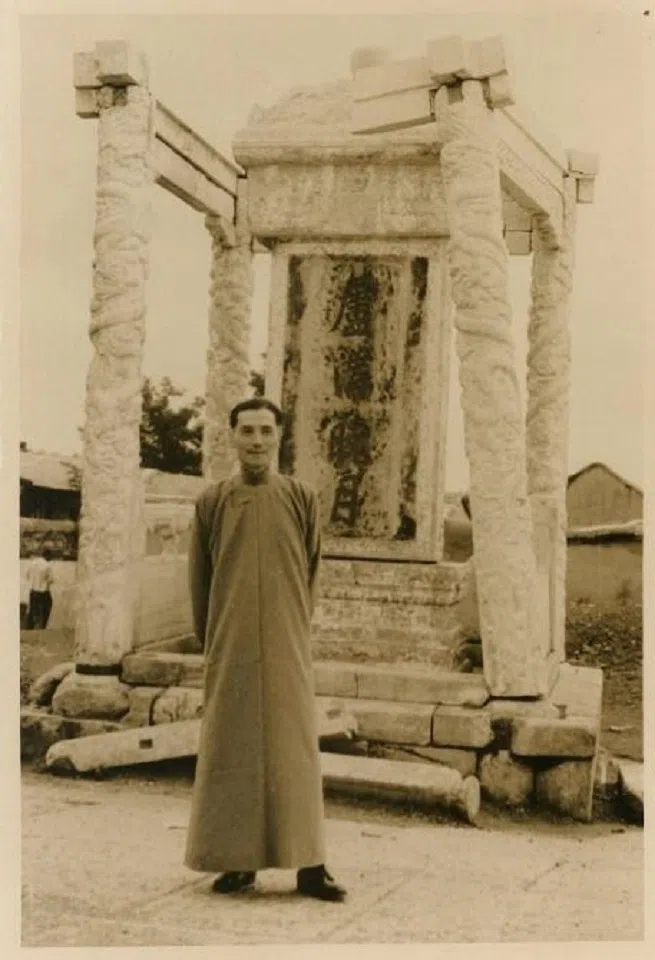

On 7 July 1947, the tenth anniversary of the Marco Polo Bridge or Lugou Bridge (卢沟桥) incident, Wang Lengzhai (王冷斋), the mayor of Wanping — a walled town southwest of Beijing — returned to his hometown and had some photographs of himself taken, each with a note written on the back.

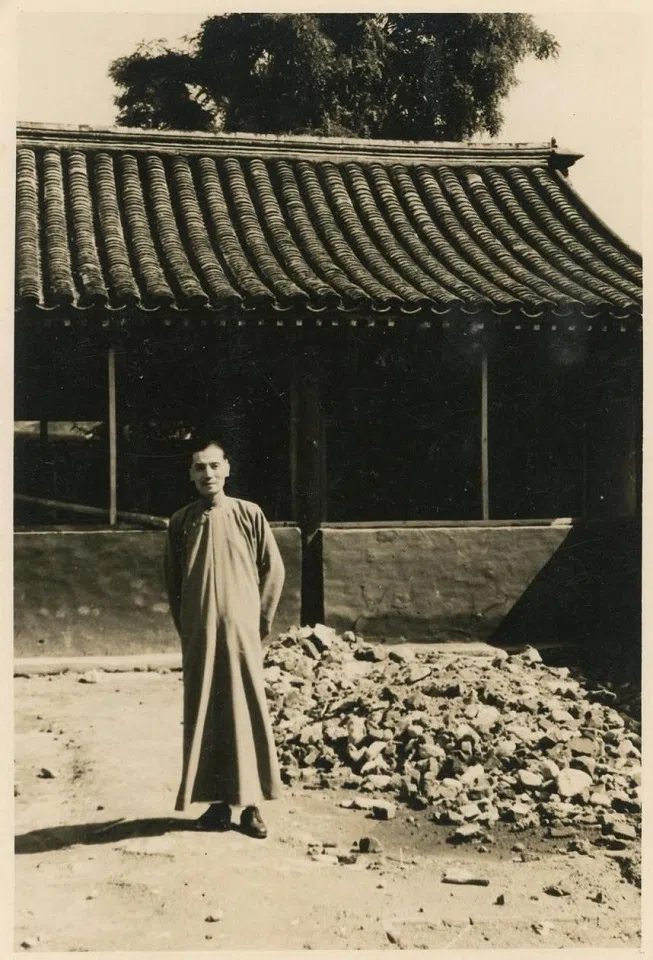

One read: “Courtyard of the Wanping county government after the disaster.”

Who knows how many heroes were sacrificed in this “disaster”?

Impending war

Japan had long planned to capture Lugou Bridge, and Wanping city protected the bridge which led directly into Beijing.

In 1936, after occupying Fengtai, the Japanese began to covet Wanping, attempting to isolate Beijing from the outside world. At that time, there were frequent negotiations between China and Japan in the area around Lugou Bridge and Wanping city.

On 1 January 1937, the Wanping county government established a commissioner’s office under the Beiping government. At the time, Wang Lengzhai was the adviser to the Beiping municipal government and head of the propaganda department, and was abruptly appointed as the commissioner and mayor of Wanping.

Before attacking Wanping, the Japanese had considered other methods to blockade Beijing. Over ten negotiation sessions were held, but China had firmly rejected each one.

The Japanese claimed to be building an airport in Dajing village, but Wang saw through their plot and declared: “The rivers, bridges, roads and fields on the map are where Chinese people have lived for generations. Ceding land is impossible, and I have not received instructions from my superiors.”

Despite Japanese pressure, Wang asserted, “I am not one of your Japanese officials. I will not sign!”

After four months, the Japanese’ plan to capture Dajing village was foiled, so they decided to attack Wanping city instead.

On 7 July 1937, gunshots of unknown origin pierced through the summer night from outside Wanping city. Wang Lengzhai received a phone call from his old classmate and Beiping mayor, General Qin Dechun. They did not expect that a war that would change the layout and history of East Asia was about to break out.

A missing Japanese soldier

Earlier that night, Japanese troops had conducted military exercises around Lugou Bridge and Wanping. When Private Shimura Kikujiro did not return to his post, the Japanese army launched a search and investigation exercise. (In the event, said soldier later returned to his unit, claiming to have lost his way in the dark after needing to relieve himself.)

Upon learning about the Japanese demand to search Wanping city for the missing soldier, Wang urgently telegraphed Jin Zhenzhong, the commander of the Wanping garrison. Jin Zhenzhong denied that the gunshots had come from the Chinese forces or there were any lost soldiers in Wanping.

Wang then drove to the Japanese Special Services Agency in Beiping for negotiation. His voice rang through the hall as he spoke:

“The gunshots came from outside the east gate of Wanping city. We have no troops stationed there, so it definitely wasn’t us who fired. Even if it had been the sentries within the city, we’ve confirmed that no shots were fired and all their ammunition is accounted for. As for the so-called missing Japanese soldier, we have sent police to search, and have not found any trace of him.

“The gates of Wanping city were closed at night, and the Japanese soldiers were holding exercises outside the city. How could anyone go missing inside the city? Even if someone did disappear, it would have nothing to do with us. Or are you employing the same tactic as the Japanese consul in Nanjing — faking a kidnapping to create a pretext for extortion?”

The Japanese side denied this outright.

China’s 29th Army headquarters issued a command: “Lugou Bridge will be your tomb. You should stand and fall with it, do not retreat.” The two armies faced off, and a battle broke out.

Flames of resistance

After the negotiations failed, China and Japan decided to jointly investigate the situation in Wanping city. However, before they even reached the city gate, Japanese troops occupied the Shagang area, with guns and artillery lined up and soldiers at the ready, just waiting for the order to attack.

The unarmed Wang showed no fear as he confronted the Japanese soldiers, insisting that they were there to negotiate as agreed at the Special Services Agency. He accused them of contradicting their commitment and warned that if the situation escalated, they would be fully responsible.

With the negotiations coming up empty, Japanese battalion commander Kiyonao Ichiki ordered the shelling of Wanping city.

China’s 29th Army headquarters issued a command: “Lugou Bridge will be your tomb. You should stand and fall with it, do not retreat.” The two armies faced off, and a battle broke out.

The Wanping government office was reduced to ruins under the Japanese artillery fire, but Wang Lengzhai moved his desk among the rubble and continued working amid the devastation.

The isolated city stood tall, and morale remained high. The flames of resistance were ignited, and the 29th Army’s roar of “Rather die in war than be a slave in a dead nation” (宁为战死鬼,不做亡国奴) echoed across the country.

For 24 days from 7 July, Wang, along with the officers and soldiers of the 29th Army, as well as the people, staunchly resisted the enemy. The isolated city stood tall, and morale remained high. The flames of resistance were ignited, and the 29th Army’s roar of “Rather die in war than be a slave in a dead nation” (宁为战死鬼,不做亡国奴) echoed across the country.

As a witness to the incident, Wang wrote a narrative poem, criticising the Japanese imperialists who started the incident and claiming that they dared not advance under the intimidation of the 29th Army. The poem reads:

A long rainbow spans Lugou/A victorious place passed down for 700 autumns/The sleeping lion on the bridge slowly awakens/As if knowing that the dagger is already at its throat/A solitary city is alerted by a single drumbeat/Signalling that its powerful neighbour is mustering troops at night

The moon is dark, stars are dim, smoke rises/Midnight approaches on the seventh night of the seventh month/In the dark shadows, the battle rages in the night/Among the troops carrying large swords, mighty men emerge/The Japanese are chilled by the frosty blade/The nomadic children dare not go south

I make the first move in this game of chess/(Toru) Morita is not confident, (Renya) Mutaguchi takes over/Reinforcements are sent to the riverbank/But they still dare not move forward

Among the rubble

About 20 days after the incident, deputy commander of the 29th Army, Tong Linge, and commander of the 132nd Division, Zhao Dengyu, were killed in action, as Beiping and Tianjin fell.

Wang Lengzhai retreated with the 29th Army, fighting in places including Jinan, Kaifeng and Xi’an. In the spring of 1939, he sought medical treatment in Hong Kong for fatigue. After the Pacific War broke out in late 1941, Hong Kong fell, and Wang went to Guilin, Guangxi province, to continue participating in the resistance.

After Japan’s surrender in August 1945, Wang was invited to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in 1946, to testify on the crimes of the Japanese military in planning and provoking the Lugou Bridge incident.

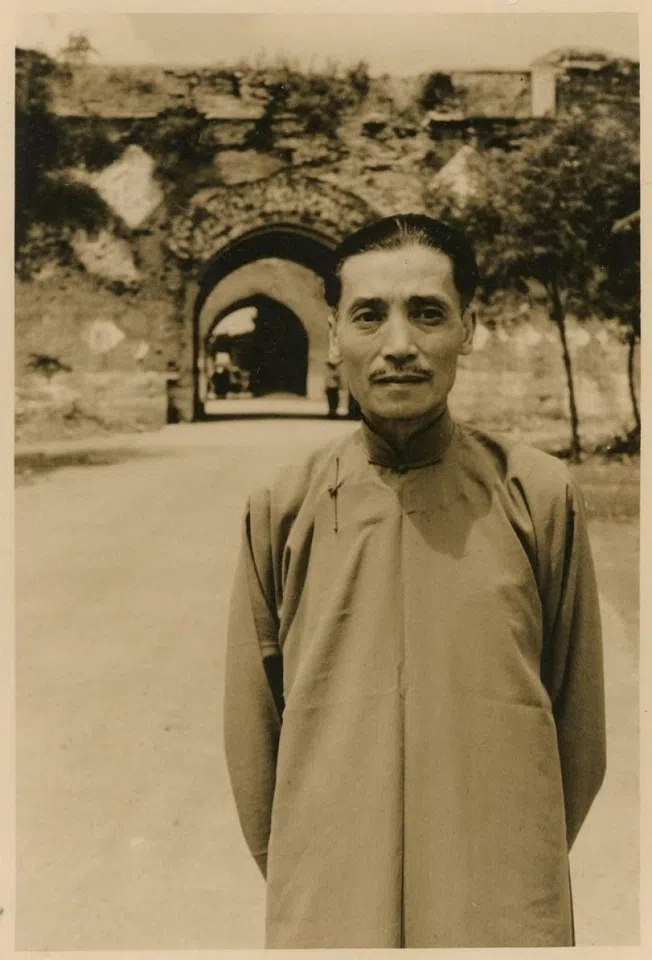

... in a photo taken at the city gate, Wang’s eyes were filled with sorrow and heaviness. Who knows whether he was remembering the comrades who had passed away during the war, or worrying about the impending civil war that was about to break out.

On 7 July 1947, after finishing his testimony at the international tribunal, Wang returned to his hometown and visited Lugou Bridge, Wanping city and the county government office. The dense bullet holes on the city gate and the rubble in the courtyard were still there, as though he had gone back in time to ten years ago.

The war was over, and from Wang’s relaxed demeanour, one could see his emotions as he returned to his hometown. However, in a photo taken at the city gate, Wang’s eyes were filled with sorrow and heaviness. Who knows whether he was remembering the comrades who had passed away during the war, or worrying about the impending civil war that was about to break out.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)