[Photos] The Catholic church in China: A story of conflict and compassion

Whether in ideology or in political reality, the Catholic church and the Chinese Communist government have remained adversaries. Nevertheless, after the end of the Cold War and the decline of communist ideology, the Chinese government began to take a more positive view of the Catholic church’s historical contributions to China. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao shares the history of Catholicism in China.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao, unless otherwise stated.)

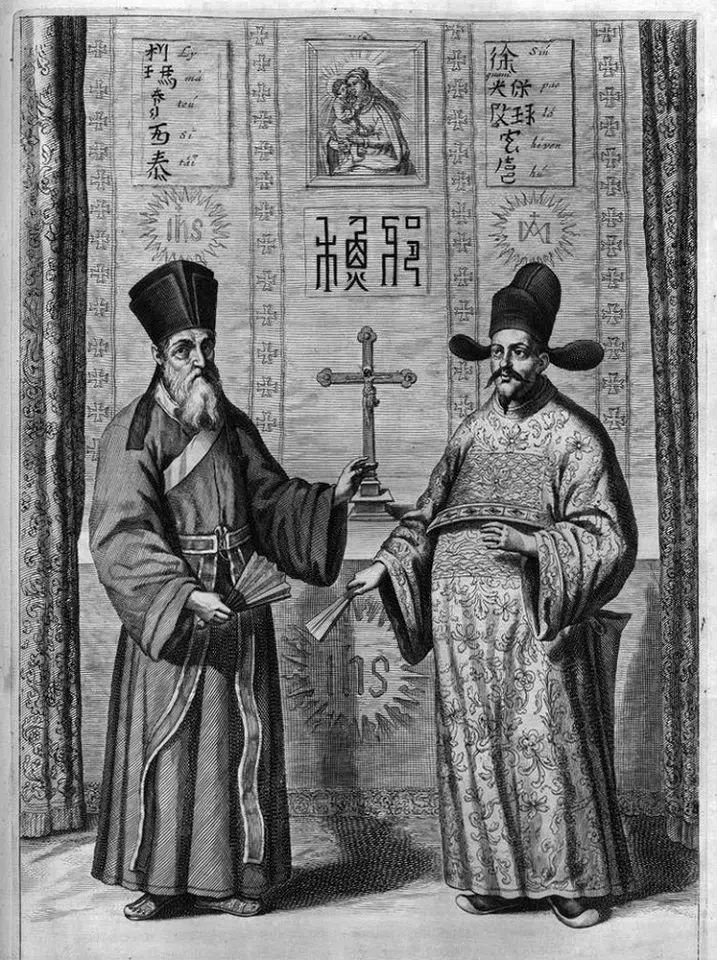

According to historical records, Catholicism first entered China during the Yuan dynasty, when missionaries were sent and succeeded in converting tens of thousands of people. In the late Ming dynasty, Italian Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci entered Zhaoqing in Guangdong province from Macau; he became one of the best-known early Catholic missionaries in China, and was highly regarded by the Chinese people.

Ricci was more than just a missionary — he was also a distinguished scholar who translated many Confucian classics and introduced them widely to the West, helping to establish China’s image in Western intellectual circles as an ancient and sophisticated Eastern civilisation. He sought to integrate the tenets of Western Catholicism with Chinese ancestral rites, which from the perspective of Christian history was remarkably forward-thinking and visionary.

Respect for Chinese cultural tradition

The Chinese people have various religious beliefs, including worshipping Buddha and honouring ancestors. Ricci reported to the Vatican that Chinese ancestral and Confucian rites were expressions of respect for one’s origins and reverence for teachers — a cultural tradition that did not conflict with Christian beliefs. His perspective was accepted by the Holy See.

Ricci’s respectful attitude towards other cultures greatly facilitated his missionary work in China, and he earned a lasting reputation in Chinese history. Several high-ranking Ming officials, including prominent writer Xu Guangqi (Paul Siu), were baptised as Catholics.

Once Catholicism accepted the positive meaning behind Chinese ancestral rites, related cultural festivals such as the Lantern Festival, Mid-Autumn Festival and Dragon Boat Festival were no longer considered incompatible; ritual objects and symbols such as altars, ancestral tablets and dragon sculptures were also not considered taboo. This grassroots approach to evangelism led to a rapid increase in Catholic followers in China.

Nevertheless, debate persisted within the Catholic church regarding the nature of Chinese ancestral and Confucian rituals, and no definitive resolution was reached. During the reign of Emperor Chongzhen of the Ming dynasty, Dominican missionary Father Juan Bautista Morales objected to Catholic acceptance of Chinese ancestral and Confucian rites, and submitted a document to the Pope recommending their prohibition. In 1645 (the second year of the Shunzhi reign in the Qing dynasty), Pope Innocent X approved Father Morales’ proposal, which sparked the centuries-long Chinese Rites Controversy.

Later, in 1650, Jesuit Father Martino Martini submitted a document to the Vatican, arguing that Chinese filial piety toward parents and elders — both during their lifetimes and after death — did not contradict Catholic doctrine. As a result, in 1656, Pope Alexander VII approved Father Martini’s petition, and permitted Chinese converts to perform ancestral and Confucian rites.

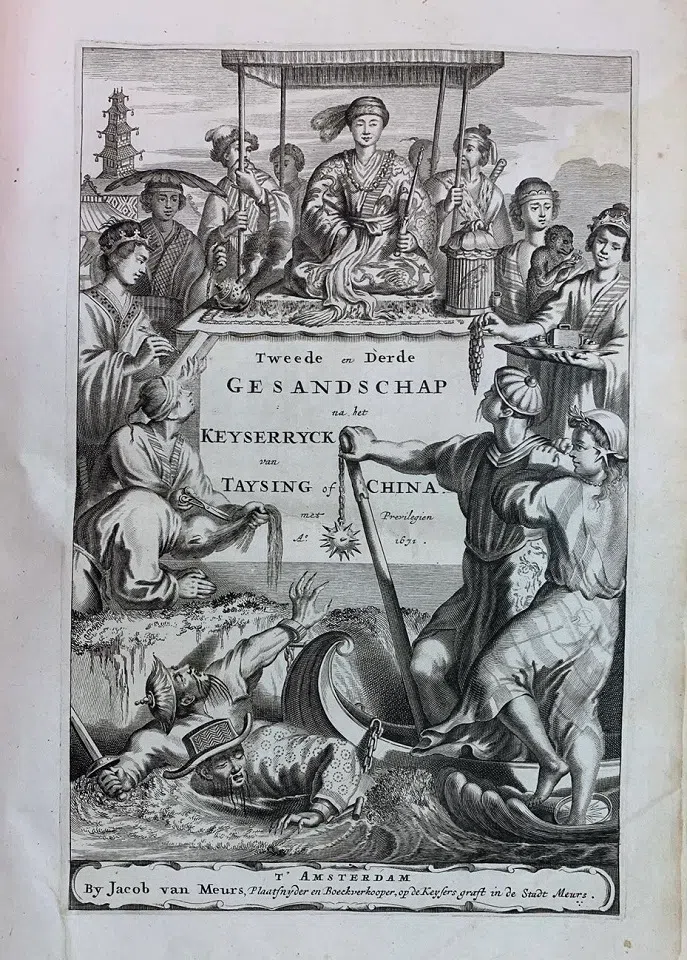

Martini was born in Trento, Italy, and was active in China during the transitional period between the Ming and Qing dynasties. He arrived in Macau in the summer of 1643 and reached Beijing in the spring of 1650, where he had an audience with the Shunzhi Emperor. That same year, he was commissioned by the Jesuit mission in China to travel to the Vatican to present the Jesuit position on the Chinese Rites Controversy, and brought with him records of the ongoing Ming-Qing war to Europe.

After intense and repeated debates, the Vatican ultimately concluded that ancestral and Confucian rites constituted idolatrous acts and were thus incompatible with Catholic doctrine. This became the fundamental reason behind the Qing dynasty’s early restrictions on Catholicism.

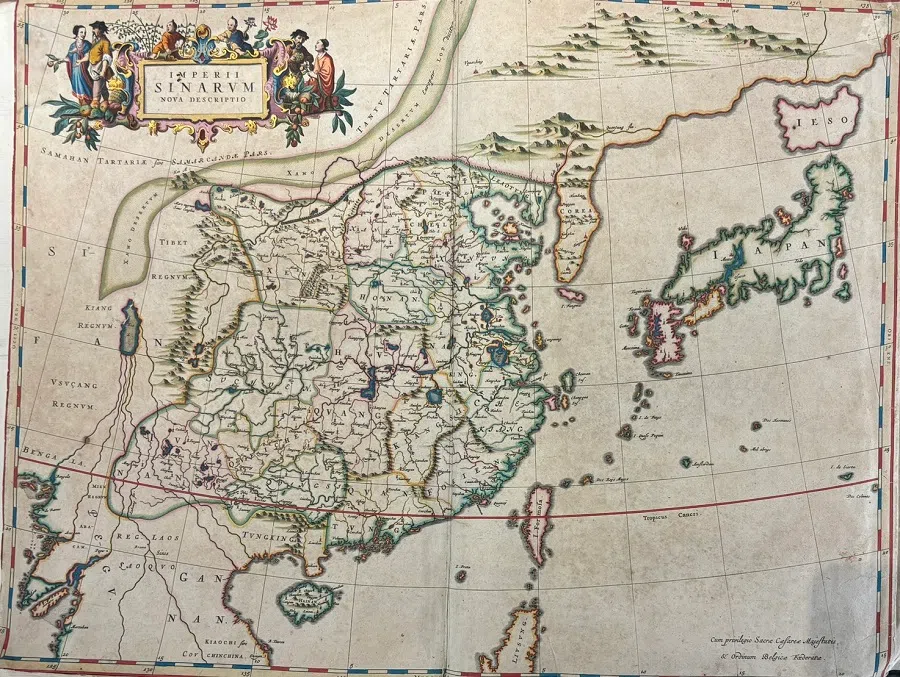

He later left for China in April 1657, accompanied by 16 other Jesuit missionaries, including Ferdinand Verbiest. Martini arrived in Hangzhou in June of 1659, and died of cholera there on 6 June 1661. During his six years in China, Martini travelled through various provinces and compiled the Novus Atlas Sinensis (New Atlas of China), the first detailed map of China’s provinces to appear in the West. Today, his tomb is in Hangzhou, and he remains respected by both the Chinese government and the public.

Continued debate on Chinese rites

Although during this period Catholicism accepted Chinese ancestral rites, in 1674 — the 13th year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign — another Dominican missionary, Father Domingo Fernández Navarrete, submitted another document on the Chinese Rites Controversy. In 1676, Navarrete published Tratados históricos, políticos, éticos y religiosos de la monarquia de China (A General Treatise on the History, Politics, and Religion of China) in Europe, reigniting fierce debate in Europe over the legitimacy of Chinese ancestral and Confucian rites.

In 1704, Pope Clement XI issued a new edict once again prohibiting such rites. The following year, he dispatched papal legate Charles-Thomas Maillard de Tournon to China to formally announce the ban.

Initially, Emperor Kangxi received Bishop Tournon with great honour. However, upon learning that the bishop’s mission was to prohibit ancestral and Confucian rites, Kangxi became enraged and ordered Tournon to leave the capital immediately.

After intense and repeated debates, the Vatican ultimately concluded that ancestral and Confucian rites constituted idolatrous acts and were thus incompatible with Catholic doctrine. This became the fundamental reason behind the Qing dynasty’s early restrictions on Catholicism.

Objectively speaking, China’s response was not particularly severe. Chinese emperors held grand ceremonies each year to honor their ancestors and Heaven and Earth, embodying the Confucian values of loyalty, filial piety, benevolence and love. Now, Western missionaries were telling the emperor that these rites were criminal acts — an attitude that reflected extraordinary cultural arrogance and a desire for dominance.

Compared with the bloody religious wars between Islam and Christianity, or the beheading of missionaries in Japan and Korea, the Chinese emperor’s response — to expel the missionaries and declare them persona non grata — was relatively mild, and far more civilised than the Catholic church’s own actions at the time, which included burning heretics alive at the stake.

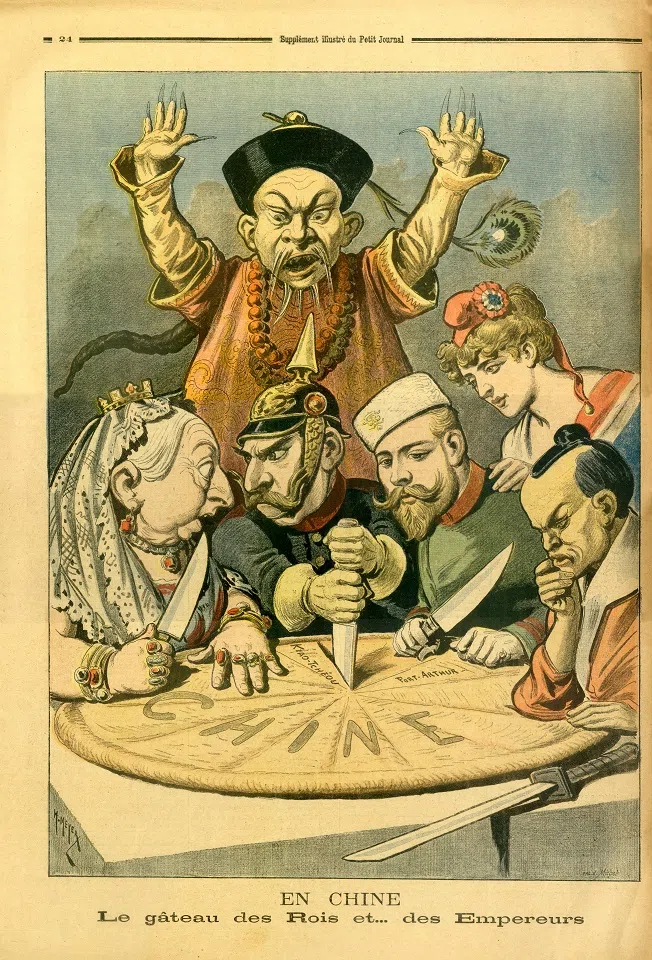

It was not until 1939 that the Vatican officially lifted the ban on Chinese Catholics participating in Confucian and ancestral rites. However, Catholicism had already reentered China after the Opium War of 1842, breaking through the Qing government’s ban on the religion. This time, it arrived alongside the imperialist aggression of Western powers armed with advanced warships and cannons, who forced opium consumption on the Chinese people.

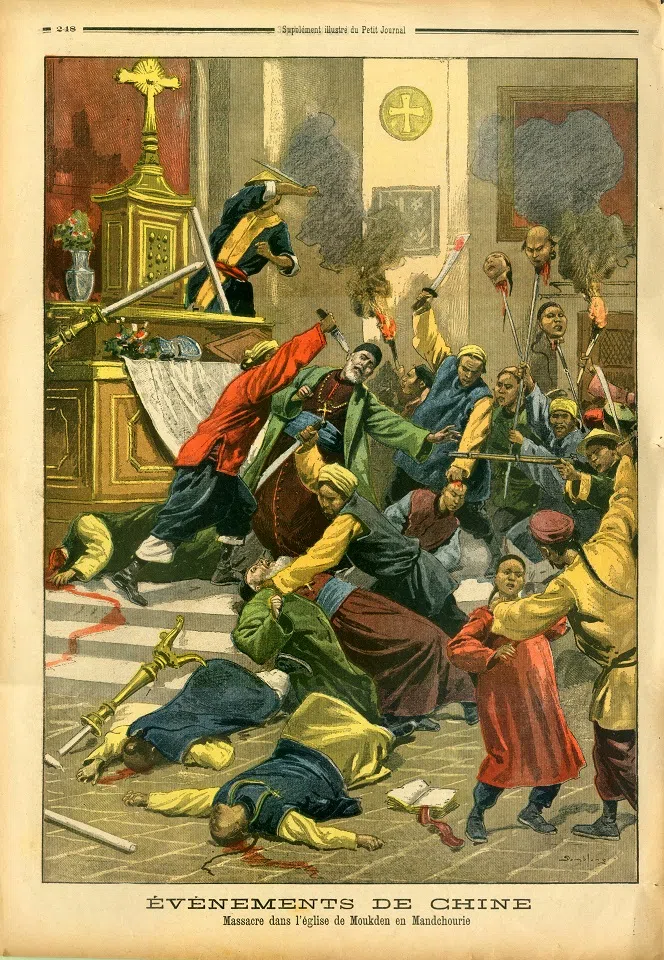

In 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion, the militant Boxers saw the imperialist forces and the church as one and the same, and launched violent attacks that resulted in the killing of many priests and converts.

Growing tension and resentment

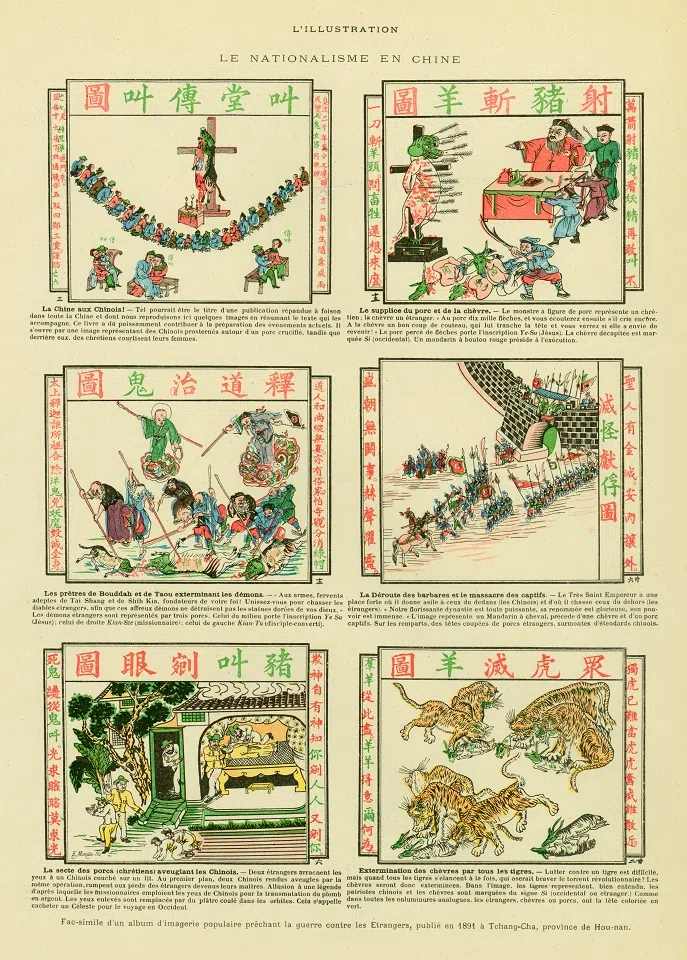

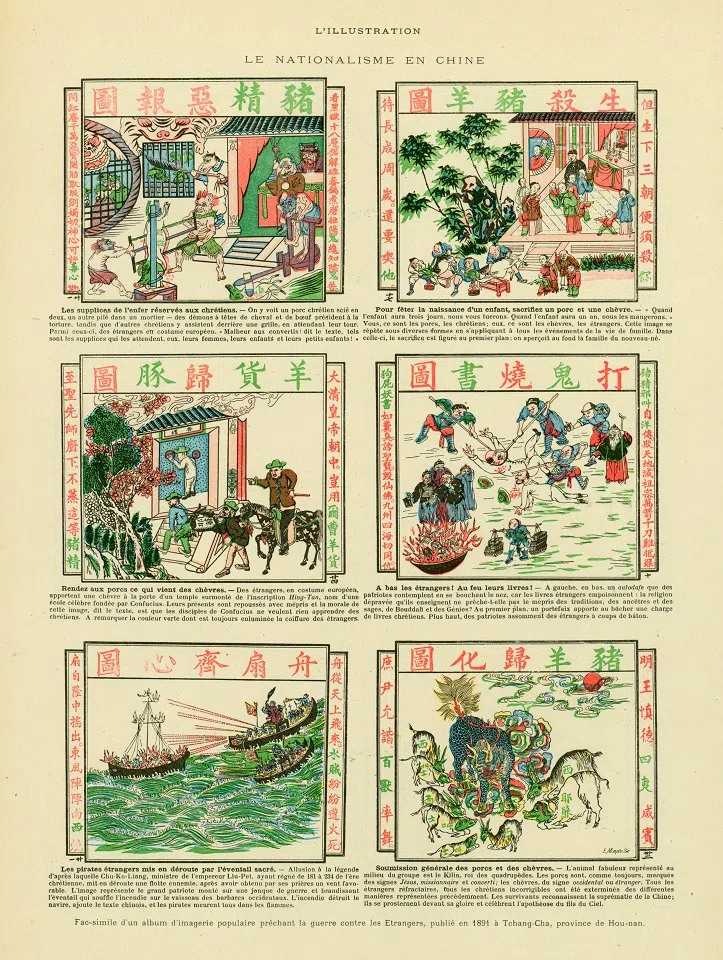

After 1860, the Catholic church expanded further into both coastal and inland regions of China. Backed by the military might of Western nations, the Qing government could no longer intervene, and the resulting friction between the church and local communities stemmed primarily from conflicts in beliefs and customs.

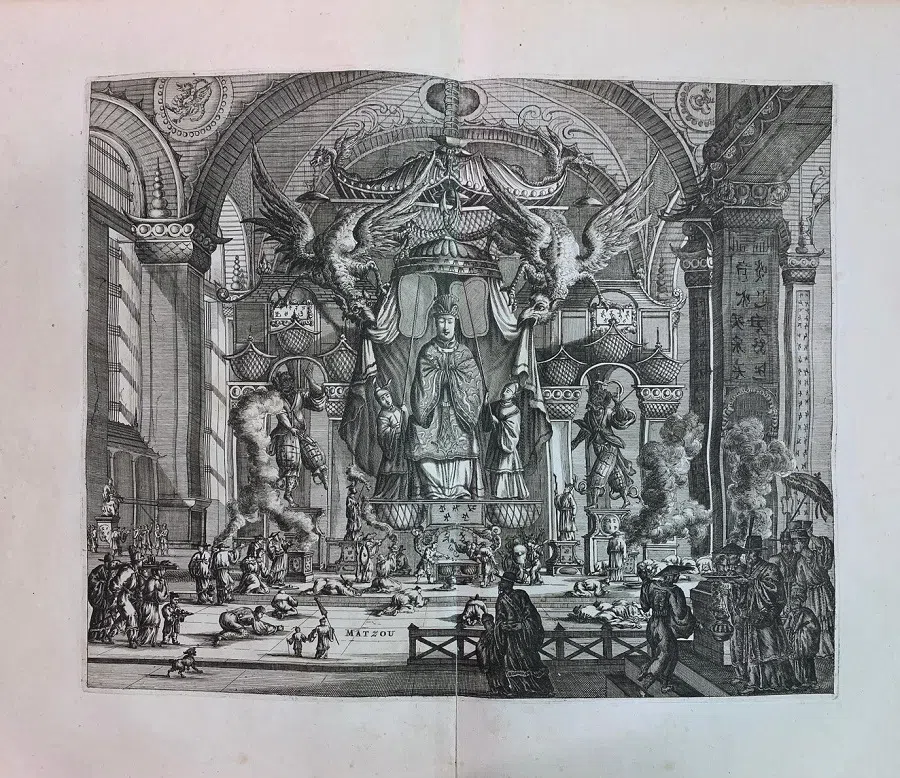

The church continued to teach Chinese people that Confucian and ancestral rites were acts of idolatry and evil. Furthermore, the Chinese translation of the Catholic Bible rendered the word “dragon” — a symbol of hell in the Western tradition — as the Chinese word “龙” (long), which traditionally represents an auspicious and divine creature in Chinese culture. As a result, the revered Chinese dragon became a satanic monster in the eyes of the Christian faith.

Moreover, when the church became involved in land and property disputes with local people, it often relied on the backing of Western governments to gain the upper hand. Although the church also carried out many charitable acts in healthcare and education, the underlying tensions and resentment continued to grow, eventually reaching a boiling point.

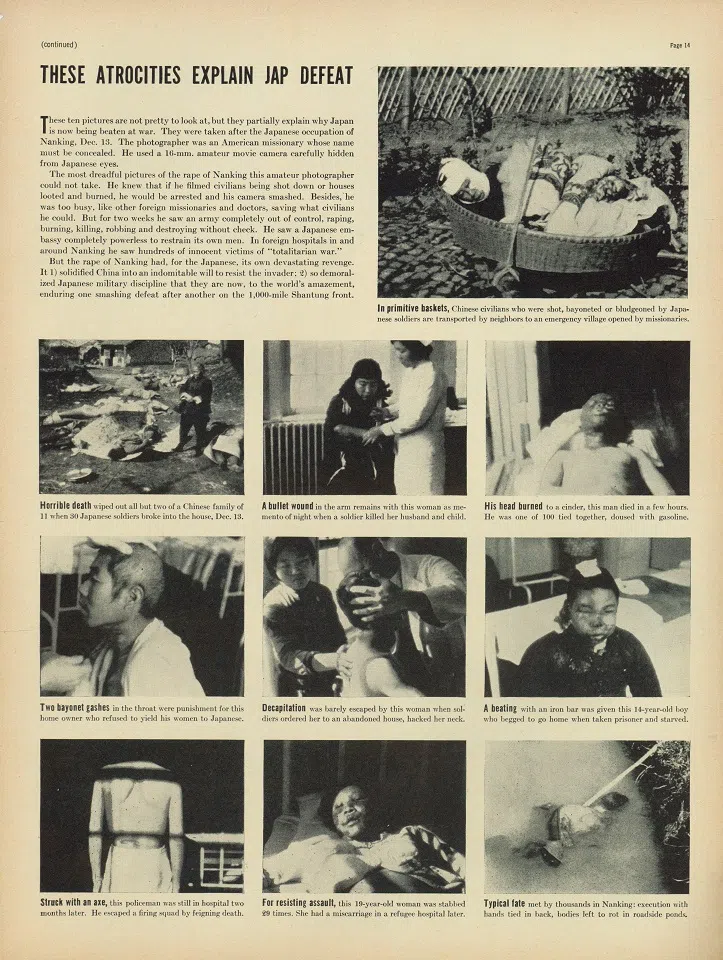

In 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion, the militant Boxers saw the imperialist forces and the church as one and the same, and launched violent attacks that resulted in the killing of many priests and converts. While these xenophobic and superstitious riots can certainly be condemned as ignorant and barbaric, they cannot be fully understood by looking at isolated snapshots. Like assessing a traffic accident, one must view the entire sequence of events in order to grasp why violence against the church erupted.

After the establishment of the Republic of China, the relationship between the church, the government and the public gradually improved, especially as the church undertook large-scale social service efforts, including building schools and hospitals, offering free medical care, and providing disaster relief. The Catholic-founded Fu Jen Catholic University became a prestigious institution, offering high-quality education with foreign faculty and excellent facilities.

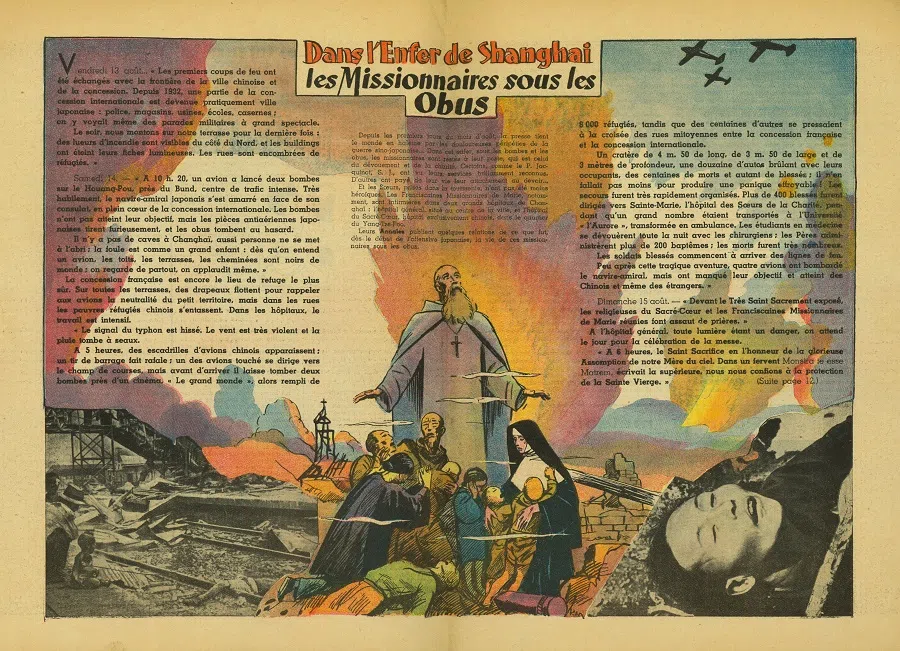

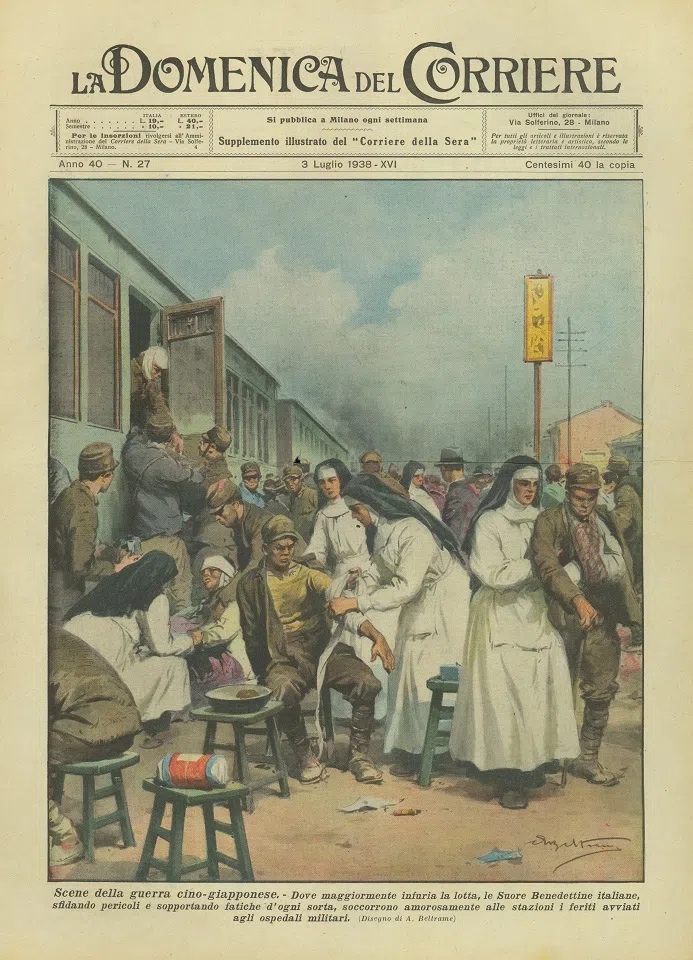

During China’s internal conflicts and wars of resistance against foreign invasion, the country faced a massive refugee crisis. The church provided shelters, food, medical aid and temporary housing. In particular, during the full-scale invasion of China by Japan in 1937, which resulted in immense casualties and destruction, the Catholic church stood firmly on the side of the Chinese people and offered extensive humanitarian support, earning widespread respect.

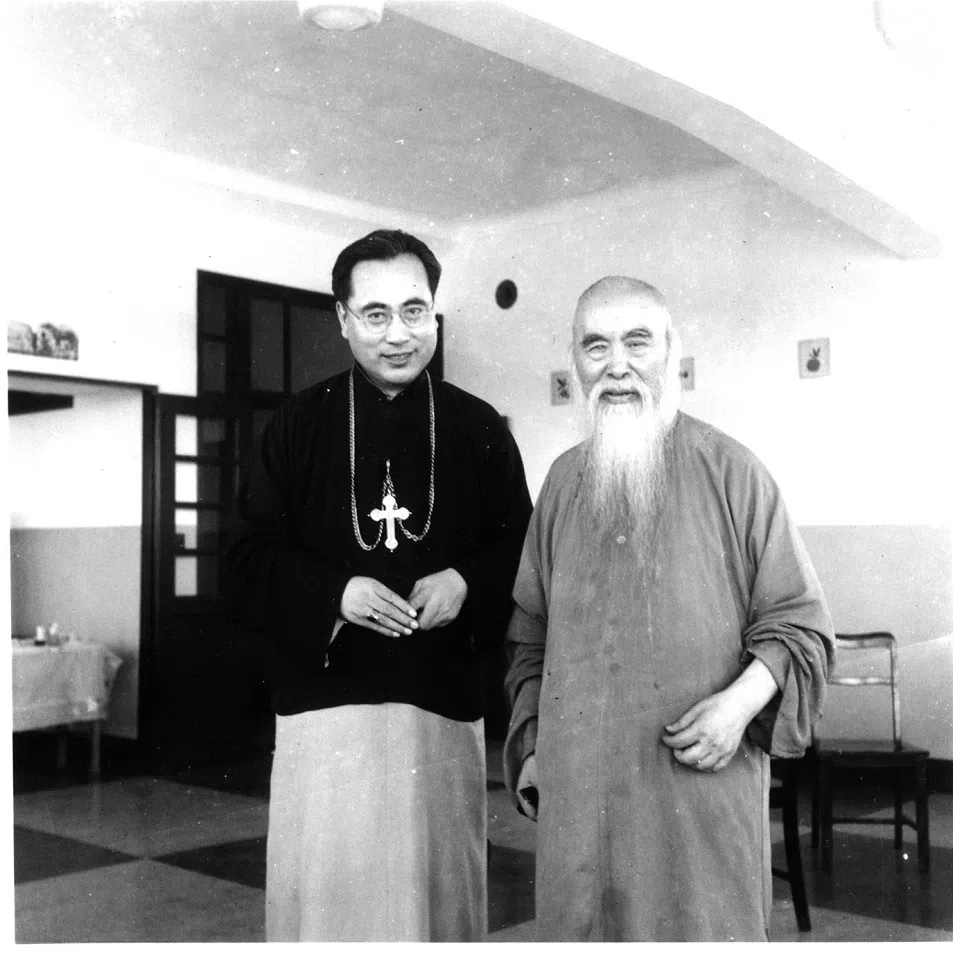

Cardinal Paul Yu Pin, the Archbishop of Nanjing, was himself a member of the Kuomintang and maintained strong ties with the Nationalist government. Under these circumstances, Catholicism flourished and achieved significant development in China.

China’s Catholic institutions relocated to Taiwan, and Fu Jen Catholic University was reestablished there.

Catholicism after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China

In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party won a comprehensive victory in the civil war and established the People’s Republic of China. From both ideological and policy standpoints, the Communist government adopted a hostile attitude towards Catholicism. Marxism regarded religion as “the opium of the people”, and the Chinese Communist Party viewed Western churches as tools of imperialist aggression.

There was also a deeper issue: communism itself, in many ways, resembled a monotheistic religion — it treated its doctrine as the sole truth of the human world and saw all other ideologies as heresy. Hence, communism and Catholicism were fundamentally at odds both ideologically and structurally.

Catholicism is centrally governed by the Roman Curia, with the Vatican recognised as a sovereign state. Churches around the world adhere to Vatican doctrines rather than obeying the laws of local governments. Therefore, all communist regimes have been incompatible with the Catholic church. After the founding of communist China, the government gradually took over church properties and expelled Western missionaries, cutting off all ties between China and the Vatican.

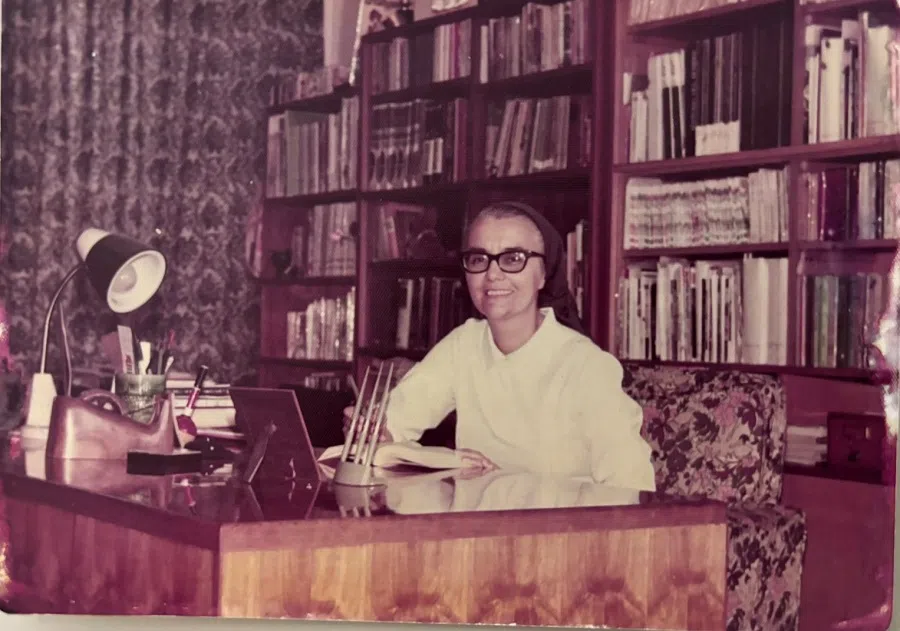

China’s Catholic institutions relocated to Taiwan, and Fu Jen Catholic University was reestablished there. In 1976, I enrolled in Fu Jen’s Spanish Department, where all instructors were Spanish priests and nuns sent by the Vatican — a tradition that has continued for decades. Cardinal Paul Yu Pin, formerly Archbishop of Nanjing, also moved to Taipei and, upon his death, was buried on the Fu Jen University campus.

As for Chinese bishops and priests who remained on the mainland, their circumstances varied depending on their political stance. The communist government established the “patriotic Catholic church”, requiring clergy to denounce imperialism.

Bishop Ignatius Kung Pin-mei of Shanghai and others refused to comply with these demands and launched resistance efforts; he was later arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment. After spending 30 years in prison, he was granted parole in 1985 and officially released in 1988, after which he sought medical treatment in the US.

... as more Chinese citizens travel abroad, Chinese Catholics have begun to visit St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, and many still attend Mass and participate in church life overseas. Both sides continue to explore ways to improve ties and hope for better cooperation in the future.

Whether in ideology or in political reality, the Catholic church and the Chinese Communist government have remained adversaries. Although the church has worked to improve relations with the Chinese government, the issue of bishop appointments has remained a major point of contention.

Nevertheless, after the end of the Cold War and the decline of communist ideology, religious life in China saw a revival, and the number of Christian believers increased significantly. The Chinese government also began to take a more positive view of the Catholic church’s historical contributions to China, in contrast to its past stance of outright rejection.

Although the Vatican and the Chinese government have yet to establish formal diplomatic relations, in recent years, as more Chinese citizens travel abroad, Chinese Catholics have begun to visit St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, and many still attend Mass and participate in church life overseas. Both sides continue to explore ways to improve ties and hope for better cooperation in the future.