[Photos] The Shandong ‘model’: A trailblazer in China’s history [Eye on Shandong series]

Shandong often played the role of a trailblazer, in more ways than one. The province was a central part of major turning points in Chinese history, and for historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao, the place holds fond memories of his first books published in mainland China.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao unless otherwise stated)

Around 1998, I began a series of publishing collaborations with Shandong Pictorial Publishing House, mainly focused on books featuring old photographs of modern China. At that time, they had launched a small-format quarterly magazine called Old Photos (《老照片》), which told stories through photographs. These stories wove together personal, family and historical narratives, written with moving prose that carried both individual emotion and social critique. The magazine created a sensation and became a bestseller.

I bought the first three issues at Beijing Sanlian Bookstore and was deeply touched as I flipped through them. By then, I had already published historical photo albums in Taiwan for many years and had collected a large number of Republican-era photographs. So, I called the office of Shandong Pictorial Publishing House. By chance, the editor-in-chief of Old Photos, Feng Keli, answered the phone. I introduced myself as being from Taiwan and offered to contribute to the magazine. He warmly welcomed the idea.

After returning to Taiwan, I organised a photo story and sent it over. My first article, “The Story of Chiang Ching-kuo”, was published in the fourth issue of Old Photos. Such a topic and set of photographs were extremely rare in mainland China, and it immediately attracted attention. Thus began more than a decade of collaboration with Feng and a lifelong friendship.

China’s civilisation began in the Yellow River basin, with Shaanxi and Henan as the core regions. But by the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, Shandong’s prominence was already clear.

Birthplace of Confucius

Before I delve into my publishing experiences with Old Photos in mainland China, let me first introduce Shandong. Although the first time I set foot in Shandong was a work-related trip to Jinan where I visited Feng, the province itself was never unfamiliar to me in terms of knowledge and historical sentiment. In our student days, Shandong was part and parcel of every Chinese history lesson.

China’s civilisation began in the Yellow River basin, with Shaanxi and Henan as the core regions. But by the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, Shandong’s prominence was already clear. The state of Qi was located there, and under the guidance of the brilliant and influential chancellor Guan Zhong, Duke Huan of Qi established a hegemonic power, becoming one of the strongest feudal states of the Zhou dynasty.

Yet Shandong’s greatest importance lay not in its regional power, but in the birth of a great thinker — Confucius. The ethical ideas he proposed became the foundation of the Chinese people’s philosophy of life and living — even today.

Born in 551 BCE in the state of Lu (today’s Qufu, Shandong), Confucius looked over court ritual and decorum. He proposed the ethical framework of benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom and trustworthiness as moral standards for the individual, the family and the state. His recorded teachings to his disciples, compiled in The Analects, became the classic foundation of Confucian thought.

Confucius travelled through various states, trying to persuade rulers to adopt his system of ideas as the basis for governing their realms. His political achievements during his lifetime were limited, and his ideas were only one among many schools of thought at the time. But during the Han dynasty, Emperor Wu of Han rejected other doctrines and elevated Confucianism as the sole orthodoxy. From then on, Confucianism became the highest moral code guiding Chinese conduct.

... the most profound aspect of Confucian thought is the principle of education for all. This idea that everyone regardless of status or class has the right to education is essentially a concept of educational human rights.

This philosophy emphasises harmony and order between heaven and earth, and the virtue of contentment in simplicity. Born of an agricultural society, the teachings were later seen as overly conservative in modern times, and were often criticised as a cause of China’s backwardness. Yet because it also stresses diligence and adherence to order, it has been seen as an essential work ethic for capital accumulation, and even as a reason for the strong productivity of overseas Chinese communities. Some even interpret it as a factor behind the rapid economic growth of mainland China over the past three decades.

From a broader perspective, the most profound aspect of Confucian thought is the principle of education for all. This idea that everyone regardless of status or class has the right to education is essentially a concept of educational human rights. To articulate this more than 2,500 years ago was truly ahead of its time; the West only came to recognise universal educational rights much later.

Chinese people have long valued their children’s education. No matter how poor they may be, parents will always find a way to give their children better schooling. This emphasis on education is the fundamental reason why, when Chinese emigrants settle overseas, they often transform their family’s destiny within three generations, rising from poverty to prosperity.

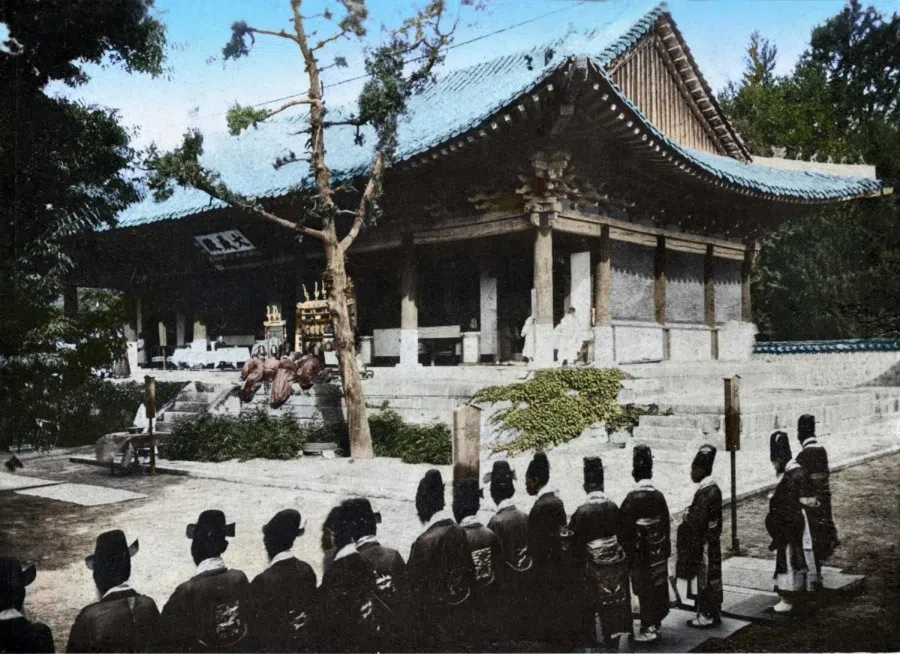

In addition to being the mainstream philosophy of the Chinese people, Confucianism also spread to neighbouring regions such as Vietnam, Korea and Japan. In Korea, Confucianism was even elevated to the level of religion and became the state creed. In 1993, Harvard professor Samuel P. Huntington published an article in Foreign Affairs magazine titled “The Clash of Civilizations?”, which made waves in the international academic community. He broadly divided world civilisations into Christian, Islamic and Confucian civilisations, arguing that the future of the world would be shaped by the coordination and conflicts among these three and their offshoots.

After the war ended, at the Paris Peace Conference, the great powers agreed to transfer Germany’s special rights in Shandong to Japan. This decision ignited large-scale student protests in China, known as the May Fourth Movement.

Rebellion, protests and civil war

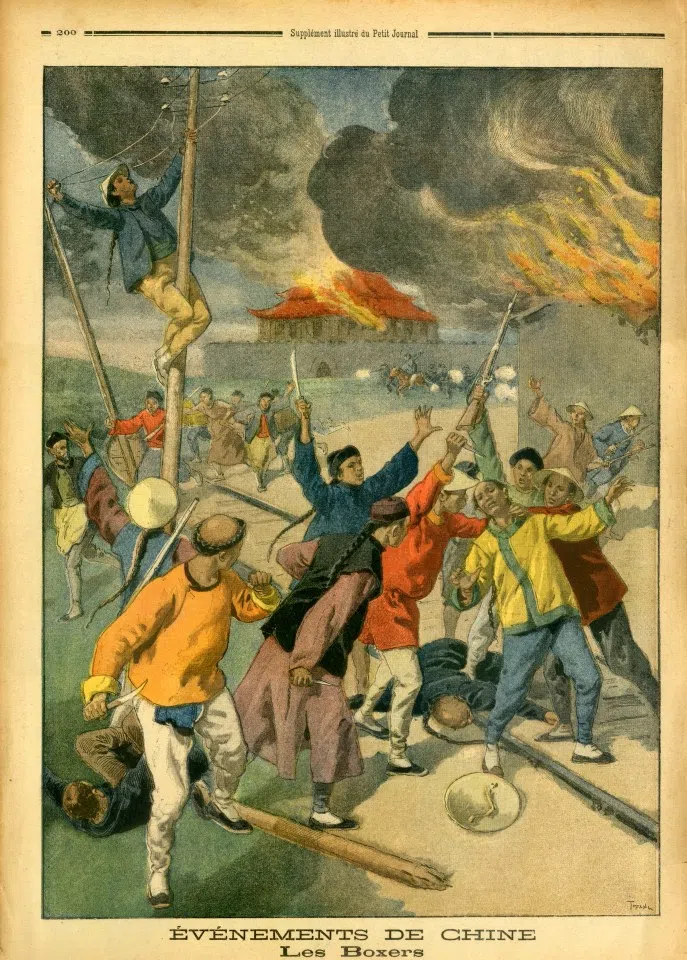

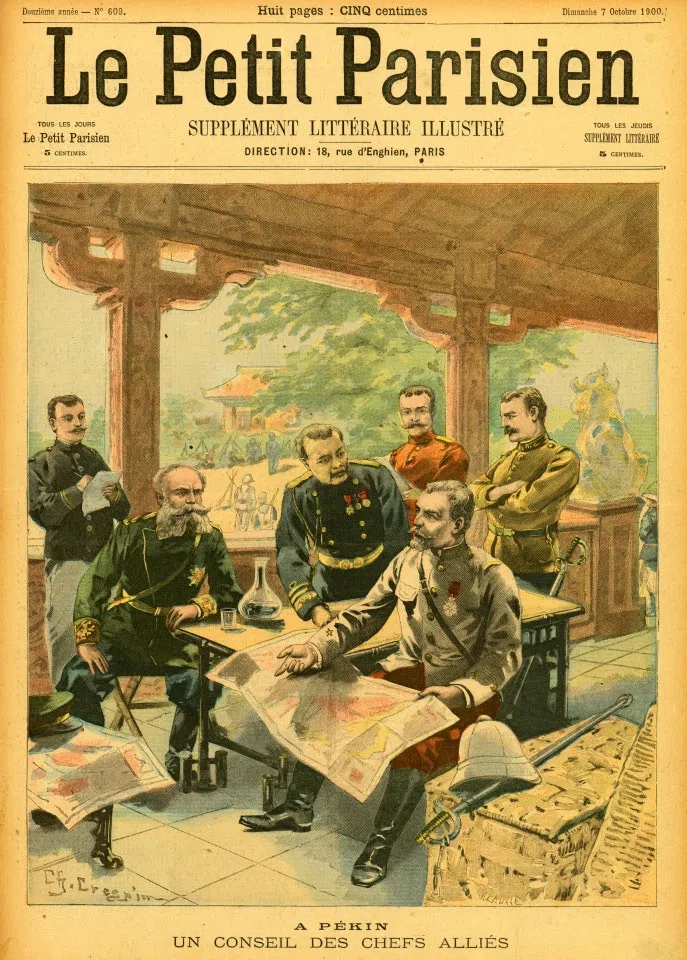

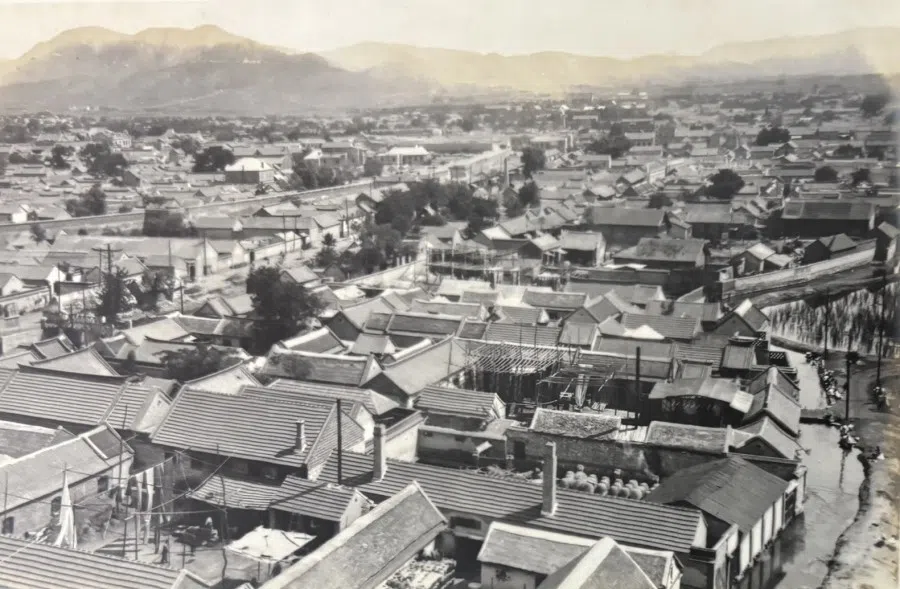

Shandong continued to play an important role in modern history. Because the land was barren and the people were generally poor, conservative thinking was deeply rooted. The Boxer Rebellion of 1900 was led mainly by Shandong peasants, who rallied under the slogan “Support the Qing, destroy the foreigners” (扶清灭洋). They stirred up superstitious beliefs that swords and bullets could not harm them, destroyed railways, and killed missionaries. The result, however, was not the expulsion of imperialism, but the deepening of China’s crisis of being carved up.

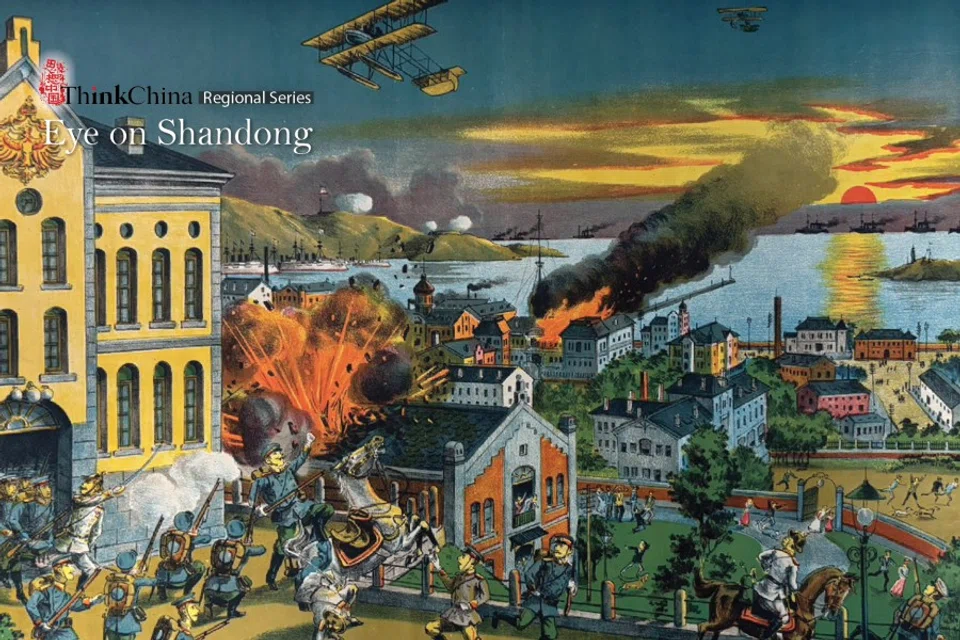

After the Boxer Rebellion, German troops from the Eight-Nation Alliance moved south to occupy Qingdao, forcing it to become a German concession. This left behind German-style streets and villas in Qingdao, and even the legacy of Tsingtao Beer, as Shandong became part of Germany’s sphere of influence.

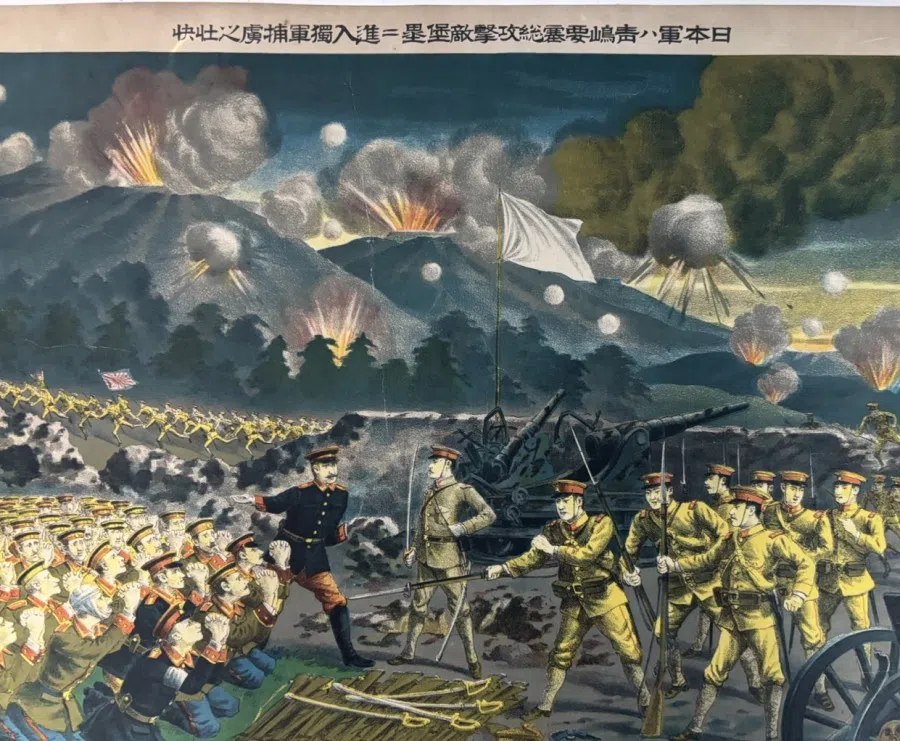

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Japanese forces entered and seized Qingdao. After the war ended, at the Paris Peace Conference, the great powers agreed to transfer Germany’s special rights in Shandong to Japan. This decision ignited large-scale student protests in China, known as the May Fourth Movement. The movement gave rise to a new generation of Chinese political and military leaders — one of them being Mao Zedong.

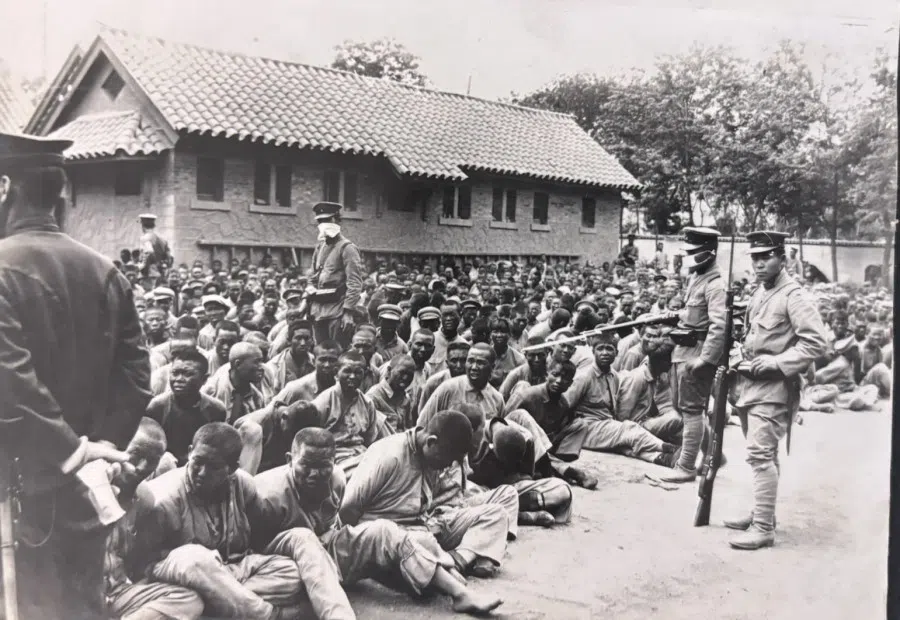

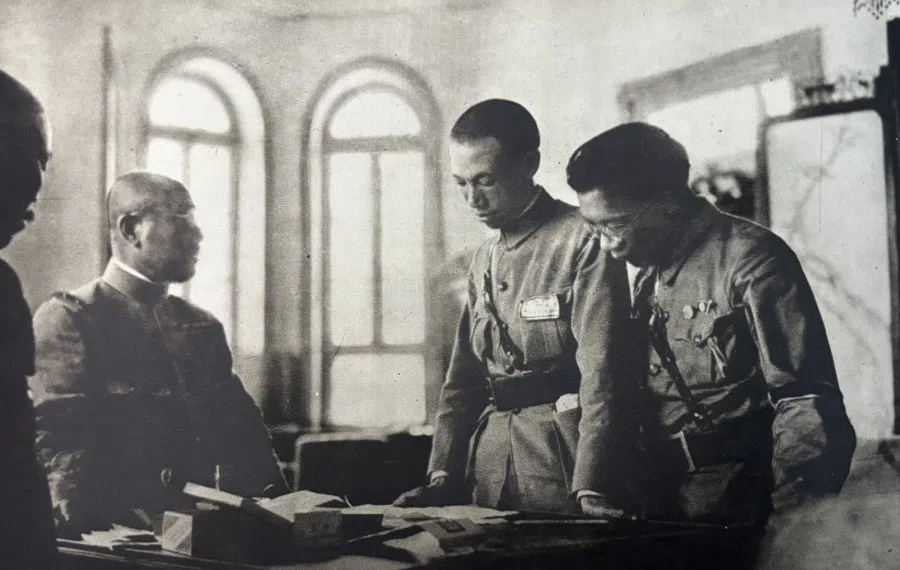

In May 1928, during the Northern Expedition of the National Revolutionary Army led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, expeditionary forces entered Shandong. To safeguard its special interests in the region, Japan dispatched troops to attack them, killing nationalist government diplomats and Revolutionary Army prisoners of war. This became known as the Jinan incident. It was a highly significant event in modern Chinese history, symbolising the attempt of China’s unifying revolutionary forces being obstructed by Japanese imperialism.

Because of this historical background, both the nationalist and communist armies had a significant proportion of soldiers from Shandong.

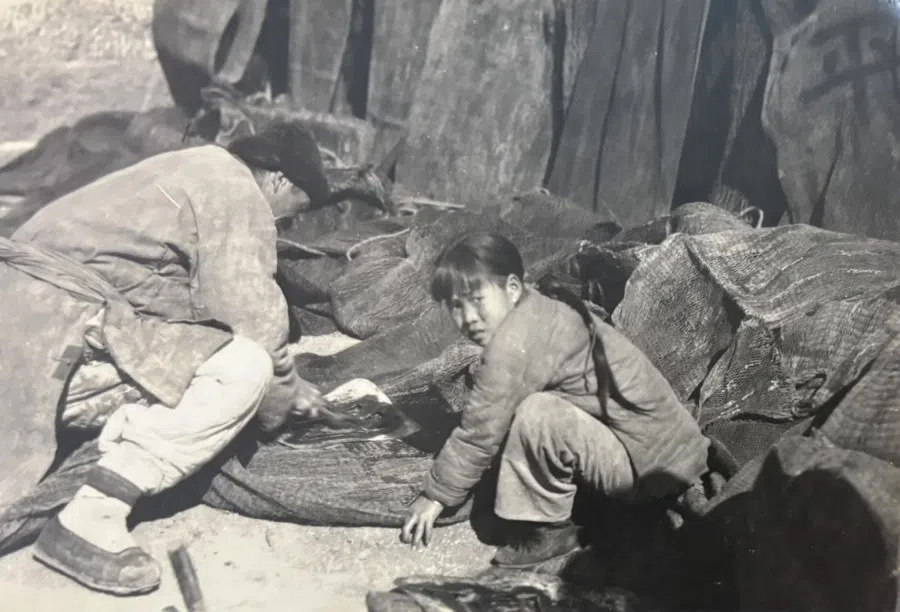

After the outbreak of the War of Resistance Against Japan in 1937, communist forces under the leadership of Mao Zedong moved into North China, establishing guerrilla bases while penetrating deep into the countryside. They trained local cadres and expanded their units. Since Shandong had a large population of impoverished peasants, many joined the ranks of the communists. The year after Japan’s defeat, the Chinese civil war broke out, and Shandong became a major battleground in North China, where the nationalist and communist armies waged a prolonged war of attrition.

In September 1948, the communists launched the Jinan Campaign and captured Jinan, the provincial capital of Shandong. It was the first major city seized by the communists and carried great strategic significance. In short, the nearly two-year war of attrition between the nationalists and communists in Shandong determined the final outcome of the civil war. Because of this historical background, both the nationalist and communist armies had a significant proportion of soldiers from Shandong.

Model province for central policies

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Shandong was long regarded as a model province for its adherence to central policies. During the Great Leap Forward of 1958, Shandong became a focal point of political propaganda, with widely publicised “miracles” such as producing 10,000 catties of grain per mu, large-scale backyard steel production, and grassroots cadres being portrayed as “good cadres loyal to Chairman Mao”.

Together with agricultural model workers, they became important symbols of state propaganda. Local Shandong media, as well as central outlets such as People’s Daily, frequently cited Shandong’s “experience”. Yet under these disastrous policies and propaganda, Shandong also became one of the provinces hardest hit by the Great Famine.

During the Cultural Revolution, the Gang of Four launched a political campaign to criticise Confucius, during which the Confucius family cemetery suffered devastating destruction — an act of profound cultural catastrophe.

During the Cultural Revolution, the Gang of Four launched a political campaign to criticise Confucius, during which the Confucius family cemetery suffered devastating destruction — an act of profound cultural catastrophe. By contrast, in Taiwan, the nationalist government launched the “Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement”, which exalted Confucian thought. That was the era of my secondary school years, when we were required to study the main Confucian classics such as The Analects and Mencius, memorising famous sayings such as: “Is it not a joy to have friends come from afar?”; “Reviewing the old and learning the new makes one a teacher”; and “What you do not wish for yourself, do not impose on others.”

... in 1964, the Republic of China President Chiang Kai-shek sent a “Shandong Peninsula Guerrilla Unit” on a mission.

New image to the world

There is also one more story worth mentioning. To underscore its determination to “counterattack the mainland”, in 1964, the Republic of China President Chiang Kai-shek sent a “Shandong Peninsula Guerrilla Unit” on a mission. The team first flew to South Korea, then travelled by ship to the waters off Shandong, before switching to small boats to carry out a surprise military raid. One man was lost, but the rest safely returned to Taiwan, where they were commended by Chiang. All the members were natives of Shandong.

Years later, after China’s reform and opening up, the commander of this unit returned to his home village in Shandong, where he was warmly welcomed by local officials and fellow villagers, in a symbolic gesture of reconciliation across the Taiwan Strait.

Following China’s reform and opening up, the traditional discipline and work ethic of the people of Shandong began to yield positive results under the new policies. The province’s economy grew rapidly, with coastal cities such as Qingdao and Yantai developing into popular tourist destinations. Qufu, the birthplace of Confucianism, was restored, and annual ceremonies honouring Confucius once again attracted participants from both China and abroad. One could say that Shandong experienced comprehensive progress across industry, agriculture, marine development and culture, presenting an entirely new image to the world.

This marked my very first set of bestsellers in mainland China, made possible through collaboration with a Shandong publisher. In this sense, Shandong often played the role of a trailblazer...

My unforgettable China breakthrough in Shandong

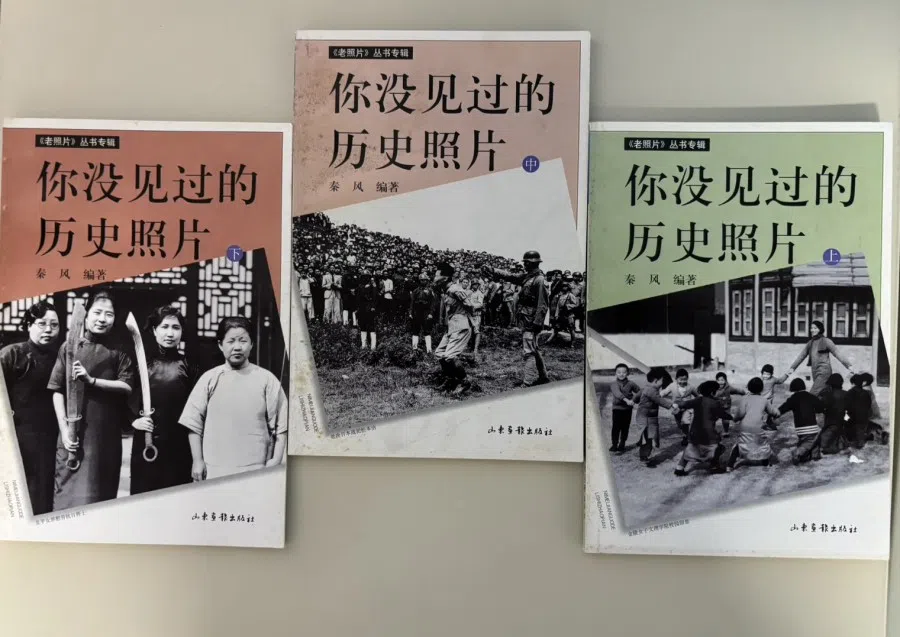

Finally, returning to what I mentioned at the beginning. After establishing my connection with Old Photos magazine, I published my first books on the mainland through Shandong Pictorial Publishing House, a three-volume set called Historical Photographs You’ve Never Seen (《你没见过的历史照片》). The content drew heavily on Republican-era photographs, breaking through the rigid stereotypes of the nationalist government that had dominated official propaganda in the past.

The books caused a sensation, becoming instant bestsellers. At Beijing Sanlian Bookstore, they held the top spot on the bestseller list for three months. This marked my very first set of bestsellers in mainland China, made possible through collaboration with a Shandong publisher. In this sense, Shandong often played the role of a trailblazer, and it remains one of the fondest memories of my life.