Survey: China the most influential and distrusted power in Southeast Asia

The State of Southeast Asia 2021 survey published by the ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute indicates that Southeast Asians' trust in China continues to trend downward. China's success in containing the pandemic domestically, and its "pandemic diplomacy" in the region have had little effect on Southeast Asians' trust deficit towards Beijing, as they are anxious over China's ability to constrain their countries' sovereignty and foreign policy choices. ISEAS academic Hoang Thi Ha notes that this trust deficit undermines China's "discourse power", and Beijing would do well to consider recalibrating its approach to the region.

The past year has perhaps been the most turbulent and disruptive one since the end of the Cold War, with the Covid-19 pandemic sweeping across the world, claiming millions of lives, ravaging economies and accentuating geopolitical tensions between major powers, especially US-China rivalry.

Early in and early out of the pandemic, China has further consolidated its position as the most influential economic and political-strategic power in Southeast Asia. Beijing also actively extended "mask and vaccine diplomacy" towards ASEAN and its member states to promote China's image as a responsible major power and shake off the stigma of the "Chinese origins" of the coronavirus.

Has China's successful pandemic containment and its charm offensives towards Southeast Asia helped to increase the region's trust towards Beijing? Has the pandemic induced any major positive shift in the region's confidence in Beijing to "do the right thing" to contribute to global peace, governance and prosperity? How does China's trust rating in the region compare to that of the US, given the Trump administration's abject failure to rein in the pandemic, economic depression, and racial and political violence?

...two juxtaposing trendlines with regard to Southeast Asian perceptions towards China, as simultaneously the most influential and the most distrusted power in the region.

Responses from 1,032 respondents to the State of Southeast Asia (SSEA) 2021 survey, which tracks the trust and distrust ratings of major powers in the region since 2019, confirms two juxtaposing trendlines with regard to Southeast Asian perceptions towards China, as simultaneously the most influential and the most distrusted power in the region.

Even though the survey report authors correctly indicate that this survey is not meant to present "the definitive Southeast Asian view" - there is no single Southeast Asian view anyway given the diversity of regional countries' outlooks - the survey findings are worth pondering as the majority of its respondents are targeted audience from the policy, research, business, civil society and media sectors in the ten ASEAN countries. They are considered as having access to the making of foreign policy and/or having influence in shaping public opinions in the region. This article examines the survey findings on the region's persistent trust deficit towards China, which should behove Beijing to introspect and recalibrate its foreign policy towards the region.

China's charm offensives towards Southeast Asia

One of the most profound geopolitical impacts of Covid-19 is that it has accelerated the power shift in Asia further towards China. The Lowy Institute's Asia Power Index 2020 reported that the US registered the largest fall in relative power of any Indo-Pacific country and that Beijing's power differential with Washington has narrowed accordingly.

Raw power aside, China's biggest gain from the pandemic is arguably political. With its successful containment of the pandemic and sustained economic growth at 2.3%, Beijing has become even more assertive domestically and vindicated internationally in the control of its one-party, authoritarian state. Buoyed by this momentum, China has aggressively engaged in "wolf warrior diplomacy" in mostly Western countries while undertaking charm offensives across the world, including in Southeast Asia.

Despite the global FDI collapse in 2020, China's FDI inflows to ASEAN in the first three quarters of 2020 reached USD10.72 billion, a 76.6% year-on-year increase...

In both economics and optics, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought Southeast Asia and China closer together. China remains ASEAN's largest trading partner for the past decade while ASEAN has overtaken the EU to become China's largest trading partner in 2020 with bilateral trade increasing by 7% in 2020. Despite the global FDI collapse in 2020, China's FDI inflows to ASEAN in the first three quarters of 2020 reached US$10.72 billion, a 76.6% year-on-year increase, whereas investment from ASEAN to China increased by 6.6%. The conclusion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement in 2020 is expected to "reinforce the economic interdependence of Asia" and "bring the region closer into China's economic orbit".

On the diplomatic front, Chinese leaders have not only engaged in "cloud diplomacy" with their ASEAN counterparts but also made efforts to visit ASEAN countries for "ground diplomacy" despite Covid-19 travel restrictions (Table 1). All these visits were aimed at amplifying the narrative of "a closely-knit China-ASEAN community with a shared future" and pacifying the South China Sea issue at a time when all key Southeast Asian claimant states, as well as the US and other Western powers, have put up a robust legal defence at the UN against China's maritime claims in the South China Sea. These direct diplomatic engagements also seek to solidify Beijing's geopolitical gains from the pandemic, projecting China as a successful and responsible major power in contrast with the US still in the grip of a deadly pandemic and withdrawn from global leadership under the Trump administration.

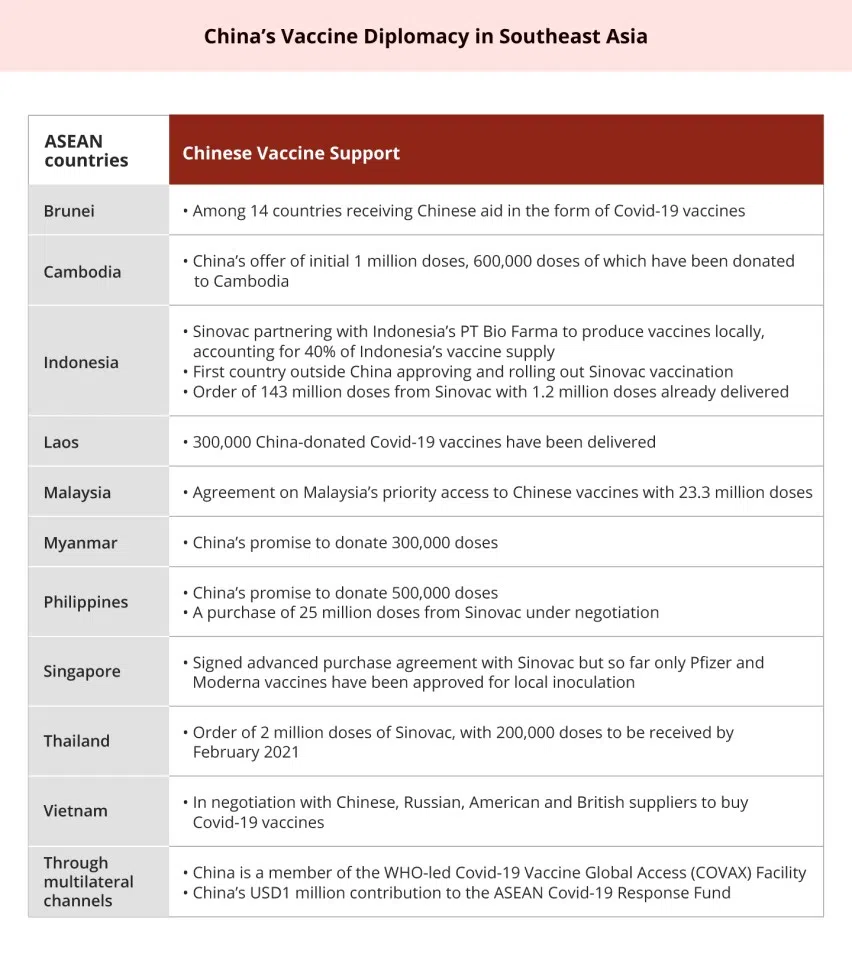

Most notably, China has turned the Covid-19 crisis into a strategic opportunity by stepping up cooperation with ASEAN countries on pandemic response. ASEAN and Chinese foreign ministers convened a special meeting on Covid-19 in February 2020, pledging to enhance cooperation in pandemic response through sharing information, mitigating supply chain disruptions of medical goods and promoting research and development of medicines and vaccines. At the virtual ASEAN-China foreign ministers' meeting in September 2020, Wang Yi proposed a "China-ASEAN vaccine friends" initiative which will put "ASEAN countries as a priority after the vaccine is put into use" and "enhance information exchange and cooperation in production, development and usage of vaccines". Southeast Asia has become a prime destination of Chinese "mask diplomacy" and "vaccine diplomacy" (Table 2). Chinese media has rallied in full swing for Chinese "vaccine diplomacy", saying that "promoting vaccine cooperation not only paves the way for a faster economic rebound, but also enhances mutual trust among China and all ASEAN countries".

China's dismal trust ratings in Southeast Asia

Have China's charm offensives over the past year paid off in terms of raised trust in the region towards Beijing? The SSEA Survey 2021 findings do not suggest so. On the contrary, the survey demonstrates a continuing deterioration of trust in China among Southeast Asian respondents, which should be disquieting to Beijing, especially in the following aspects.

The percentage of respondents who distrust China increased from 51.5% in 2019 to 60.4% in 2020 and 63% this year.

Growing trust deficit in China despite recognition of its Covid-19 support

Most Southeast Asians are currently preoccupied with the Covid-19 pandemic, viewing it the top challenge facing the region, and duly recognise China's Covid-19 support in this respect. 44.2% of respondents chose China as the dialogue partner that has provided the most help to the region on Covid-19, well above second-place Japan (18.2%). China was the top choice in eight ASEAN countries, except Vietnam which chose the US as providing the most help and Myanmar whose top choice is Japan.

Recognition of China's Covid-19 support, however, has done little to improve China's trust ratings among Southeast Asians which have been trending downward every year since this survey started. The percentage of respondents who distrust China increased from 51.5% in 2019 to 60.4% in 2020 and 63% this year. In all ASEAN countries, the levels of distrust towards China are higher than the trust levels. Additionally, the share of respondents who think that "China is a revisionist power and intends to draw Southeast Asia into its sphere of influence" also increased from 38.2% in 2020 to 46.3% this year. Meanwhile, despite Chinese "mask and vaccine diplomacy", only 1.5% in both last year and this year' surveys view China as "a benign and benevolent power".

To the surprise of many, the survey results show a clear contrast between China's deteriorating distrust ratings and the US' improving trust ratings which increased from 30.3% in 2020 to 48.4% in 2021.

Trust in the US on the rise, against all odds

To the surprise of many, the survey results show a clear contrast between China's deteriorating distrust ratings and the US' improving trust ratings which increased from 30.3% in 2020 to 48.4% in 2021. Likewise, the share of respondents having confidence in the US as a strategic partner and provider of regional security increased from 34.9% to 55.4%.

Washington also joins the EU as the two major powers in which Southeast Asians have the strongest confidence to provide leadership in maintaining the rules-based order and upholding international law and championing the global free trade agenda. This is despite the fact that China actively pushed through the RCEP agreement and recently expressed intention to join the CPTPP which Washington had chosen to stay out of. As regards the forced "binary choice", 61.5% of the respondents chose the US, up from 53.6% last year whereas 38.5% chose China, down from 46.4%. At the country level, seven ASEAN countries chose China last year, which has reversed to seven siding with the US this year.

The survey report attributes this positive view of the US to the prospects of the new Biden administration with its "Build Back Better" promise, including revitalising American global leadership and engagement with the region. In the 2020 survey, 60.3% of the respondents said that their confidence in the US would increase if there was a change in American leadership. This year's survey results verify just that. Even if many analysts have argued that the world and the region have changed and there is no way back to a pre-Trump time, this survey shows that the Biden administration will nonetheless enjoy a big reservoir of goodwill and welcome among Southeast Asians.

When asked about what China can do to improve relations with regional countries, 68.9% of the respondents suggested that "China should respect my country's sovereignty and not constrain my country's foreign policy choices".

Between economic interdependence and strategic dependency

The survey carries forward two juxtaposing trendlines from its previous editions with regard to Southeast Asian perceptions of China's influence. On the one hand, Southeast Asians overwhelmingly view China as the most influential economic power in the region (76.3%). Yet, 72.3% of respondents in this cohort are concerned about China's growing regional economic clout. The same anxiety with even a higher degree (88.6%) applies to China's political-strategic clout, and it is pronounced in both the mainland and maritime parts of Southeast Asia. Underlying this perception is the worry shared by 51.5% of respondents that China's economic and military power could be used to threaten Southeast Asian countries' interest and sovereignty, including the use of economic tools and tourism to punish their foreign policy choices.

When asked about what China can do to improve relations with regional countries, 68.9% of the respondents suggested that "China should respect my country's sovereignty and not constrain my country's foreign policy choices". This is the top choice for respondents from five ASEAN countries - Cambodia (100%), Malaysia (87.5%), Myanmar (76.5%), Singapore (68.4%) and Thailand (70%). The top choice for the Philippines (90%) and Vietnam (84.4%) was that "China should resolve all territorial and maritime disputes peacefully in accordance with international law", which essentially boils down to sovereignty concerns as well.

It is clear that Southeast Asians are acutely aware of the growing strategic vulnerabilities facing their countries as they increasingly bend towards China's economic orbit. This interdependence-dependence conundrum explains their persistent ambivalence towards Chinese growing influence in the region.

Policy implications for China

The above survey results are worth pondering, but they are not surprising. Power asymmetry and geographic proximity between China and Southeast Asia naturally entail awe and anxiety in the region over China's power. This reality is well captured by Bilahari Kausikan: "As a contiguous big country, China is always going to be influential in Southeast Asia. For the same reason, because it is a contiguous big country, China is always going to evoke concerns in Southeast Asia. In this apparent contradiction lies the essence of the relationship. [...] China is undoubtedly influential but distrusted."

Recognising these structural factors, however, does not mean denying the importance of agency in China-Southeast Asia relations. Beijing needs to reflect upon its neighbourhood strategy and take proactive steps to address its trust deficiency among Southeast Asians because "a shortage of empathy towards its neighbours has further hampered China's welcome in the region."

Southeast Asians' persistent and growing trust deficit towards China is both a drag and a blow to Beijing's ongoing efforts to develop its own "discourse power".

The survey results expose the limitations of economic determinism embedded in Beijing's neighbourhood strategy which relies on the structural factors of geography, history and Chinese economic gravity as its anchors. Although perceptions do not equate to policies, the underlying cognitive bias against Beijing among the respondents continues to inform and influence the process of foreign policy-making in Southeast Asian countries. Consequently, while strengthening economic relations with China, these countries also seek to maximise the space for the exercise of their strategic autonomy and diversify their foreign policy options, be it about securing multiple channels of access to Covid-19 vaccines or pursuing open regionalism through ASEAN-led mechanisms to keep the regional order open and inclusive.

Southeast Asians' persistent and growing trust deficit towards China is both a drag and a blow to Beijing's ongoing efforts to develop its own "discourse power". Thomas Joscelyn views it as the power to control and set the narrative so as to influence how people should think about the world. In the same vein, Nadège Rolland defines it as "the ability to exert influence over the formulations and ideas that underpin the international order". Promoting this discourse power requires more than finetuning China's communication tools or trying to come up with some more persuasive formulations than the "community of common destiny/shared future". Rather, it must start with a fundamental recognition that Southeast Asian countries have a mind of their own in defining and pursuing their national interests. Therefore, their defiance to or disagreement with China on certain issues must first of all be attributed to their indigenous concerns over their national interest as they define it, and not because they are acting as lackeys of foreign powers. As pointed out by Donald Emmerson in his edited book The Deer and the Dragon: "Structure matters. But agency is not a property of the strong alone."

The South China Sea issue is a case in point. Chinese leaders and diplomats often dismiss the South China Sea tensions as externally induced, blaming foreign forces for "stirring up trouble and creating tensions in the South China Sea" and "driving a wedge between China and ASEAN [which] goes against the will of the people in our region". The survey findings, however, defy this narrative. When asked about their top two concerns about the situation in the South China Sea, the majority of respondents (62.4%) chose "China's militarisation and assertive actions", followed by "Chinese encroachments in the exclusive economic zones and continental shelves of other littoral states" (59.1%). Beijing's maritime encroachments is the top concern for the directly affected littoral states (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam) while its militarisation and assertive actions create the biggest worry among respondents from Myanmar, Singapore and Thailand.

Meanwhile, only 12.5% express worry over the US' increased military presence in the area. Whether Beijing truly believes in its own propaganda or not, it is obvious that its narrative of blaming the South China Sea tensions on external involvements does not work in changing the region's perceptions towards China's actions or alleviating their legitimate concerns over the South China Sea situation. Continuing to engage in this narrative will not only deny the agency of Southeast Asian states but also deny China a chance for introspection and recalibration of its foreign policy, including in the South China Sea.

Many surveys, similar findings

Southeast Asia's scepticism towards China did not emerge in a vacuum. The SSEA Survey 2021 findings share some key trendlines with other international surveys concerning China. The Lowy Institute Asia Power Index 2020 recorded China's slight gain in economic relations (+1.4) but a bigger loss in diplomatic influence (-5.1). The Pew Research Centre's report in October 2020 pointed to historic highs in unfavourable views of China in the developed countries. A survey conducted by the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) in September-October 2020 in 13 European countries also indicated that European public opinion on China in the age of Covid-19 has gone more negatively with the exceptions of Russia, Serbia and Latvia. In Australia, the most prominent target of China's "punish diplomacy" and "wolf warrior diplomacy" over the past year, trust in China has reached its lowest point: Only 23% of Australians said they trust China to act responsibly in the world, and 9 out of 10 wanted Australia to find other markets to reduce economic dependence on China.

In its drive to strengthen its discourse power, China should reckon that its behaviour in other parts of the world is keenly observed by Southeast Asian countries. This may discourage them from going out of the way to provoke China, and at the same time continue to motivate their ongoing effort to diversify their foreign policy options as part of the hedging strategy in dealing with China.

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2021/15 "Southeast Asians' Declining Trust in China" by Hoang Thi Ha.

The State of Southeast Asia: 2021 Survey Report is published by the ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

Related: Wang Yi's Southeast Asia tour: How China woos Southeast Asia in view of US-China competition | Overzealous attempts by China and the US to sway Southeast Asia countries counterproductive | Unfavourable views: Southeast Asia's perceptions of China and the US worsen amid Covid-19 | China's Southeast Asian charm offensive: Is it working? | Vaccine diplomacy: China and India push ahead to supply vaccines to developing countries

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)