Why Chinese hawks cheer Takaichi's win

Takaichi’s landslide win and Japan’s hardline turn are not just Tokyo’s story. In Beijing, it gives hardliners moral cover, reframes tension as destiny and turns miscalculation into a dangerous new logic for East Asia. Commentator Deng Yuwen analyses the situation.

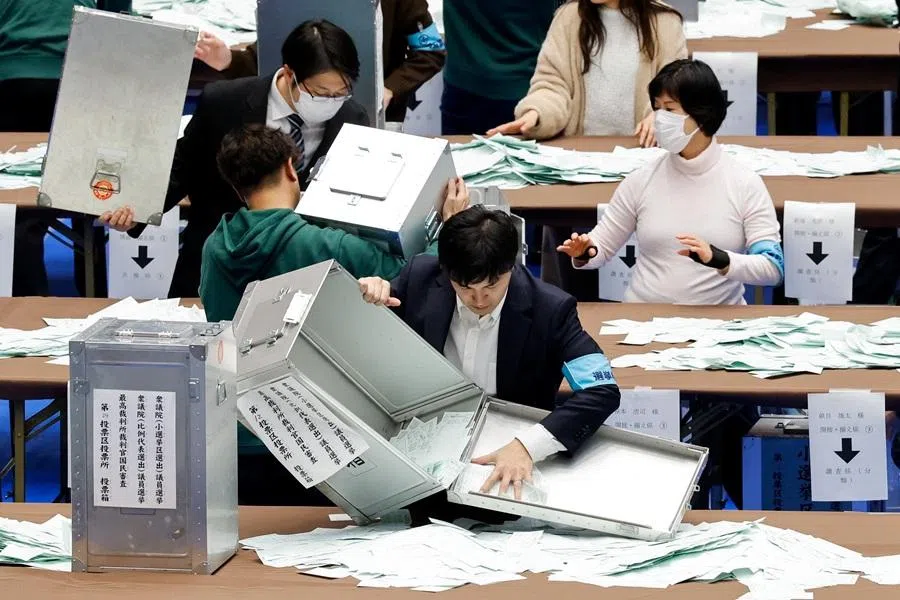

Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has secured more than two-thirds of the seats in the House of Representatives, achieving its strongest electoral result since World War II. The outcome has instantly elevated Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi — previously lacking a solid power base within her own party — into the most powerful political figure in Japan today, while granting her government the widest possible policy mandate from the electorate.

Domestic reaction in Japan has been predictably jubilant. Yet the impact of this election extends far beyond Japan’s borders. Mainstream opinion in the US has largely welcomed the result. More striking still, hardline nationalist voices in China have also expressed a form of approval. That a single election outcome could satisfy actors with such divergent positions, values and strategic goals is not a sign of emerging consensus. On the contrary, it is a warning that systemic risk is rapidly accumulating — one that could push East Asia toward its most dangerous security environment since the end of the Cold War.

Japan’s choice: turning security anxiety into political authorisation

For Japan, the significance of this election far exceeds that of an ordinary transfer of power.

The political manoeuvre led by Takaichi — dissolving parliament and calling an early election — was, in essence, a nationwide referendum on whether the postwar order should continue to define Japan’s strategic identity. Over the past seven or eight years, Japan’s security policy has operated within an elastic zone of interpretation: the pacifist constitution formally remains in place, yet policy boundaries have been repeatedly stretched; “exclusive defence” is still invoked rhetorically, even as Japan moves steadily closer to becoming a normal military power in substance.

A politically stable Japan with a rightward-shifting public mood and a clear, hardline position toward China is precisely the forward anchor the US seeks in the Indo-Pacific.

This election signals that Japanese society is now prepared to supply political and institutional legitimacy to that reality. Voters were not merely endorsing a particular leader. They were granting approval to the hardline national security trajectory represented by Takaichi and the radical right within the LDP. As a result, a tougher stance toward China is no longer a personal style or factional preference — it has acquired the imprimatur of mainstream public opinion.

America’s satisfaction: a frontline state finally takes shape

The positive reaction in the US follows a clear strategic logic.

From Washington’s perspective, Japan has long faced a structural dilemma: it depends heavily on the US for security, yet remains politically constrained by its postwar framework, limiting its ability to function as a true frontline actor. As US-China rivalry has become the defining feature of the era, the LDP’s landslide victory appears to resolve this contradiction, at least for now.

A politically stable Japan with a rightward-shifting public mood and a clear, hardline position toward China is precisely the forward anchor the US seeks in the Indo-Pacific. The more Japan completes its process of military “normalisation”, the more the burden along the first island chain can be shared. Whether a fully normalised Japanese state might, over the long term, generate strategic frictions with US interests is not Washington’s immediate concern.

Once Japan is positioned as a key node in the effort to contain China, constitutional revision and military expansion are treated in the US strategic calculus as costs — not red lines. As long as Japan does not drag the US prematurely into an uncontrolled war with China, Washington has little incentive to apply the brakes.

Chinese hardliners’ ‘approval’: the confrontation narrative is confirmed

More alarming than the American response, however, is the reaction among China’s hardline nationalists.

Within this framework, any future Sino-Japanese friction ceases to be a policy dispute and is instead framed as historical continuation. Any forceful Chinese response can be justified as a “legitimate reckoning”.

From their perspective, the LDP’s victory and Takaichi’s successful gamble are not bad news but welcome confirmation. The result is not interpreted as an expression of democratic vitality in Japan, but as definitive proof that Japan as a whole is shifting rightward and that militarism is resurfacing. It completes the final missing link in a longstanding narrative: Japan’s alignment with US efforts to contain China is not the product of coercion, but a deliberate choice.

Within this framework, any future Sino-Japanese friction ceases to be a policy dispute and is instead framed as historical continuation. Any forceful Chinese response can be justified as a “legitimate reckoning”. This helps explain why all three sides — Japan, the US and Chinese hardliners — can simultaneously welcome the same outcome. Japan sees political authorisation, the US sees a frontline anchor and Chinese hardliners see moral justification for confrontation.

Takaichi’s likely miscalculation: expecting China to accept reality

Takaichi is hardly unaware of the risks. When she declared last November during a parliamentary session that “a Taiwan contingency is a Japan contingency”, she understood that the statement would have a structural impact on Sino-Japanese relations. Yet instead of responding to Beijing’s demand that she retract the remark, she dissolved parliament and called an early election.

Her calculation was clear: if this hardline posture received overwhelming and durable democratic endorsement, China would ultimately have no choice but to accept it as a political reality and resume a tense yet functional working relationship with her government.

In this sense, the snap election was a calculated gamble — intended to demonstrate to Beijing that confrontation was not a personal provocation but an irreversible national choice. That calculation, however, is likely based on a profound misreading of how China interprets political legitimacy.

Under such domestic pressure, China’s leadership will find its room for manoeuvre sharply constrained. Any attempt at de-escalation risks being portrayed as capitulation on historical and sovereignty issues.

China’s interpretation: this is not just Takaichi’s problem

From Beijing’s standpoint, the LDP’s landslide victory will not be read simply as evidence of Takaichi’s personal strength. It will be interpreted as a signal that Japanese society as a whole has chosen confrontation.

If inflammatory rhetoric came from a single politician, China might still distinguish between the individual and the state. But once the same policy line is ratified through the dissolution of parliament and an early election, that distinction collapses. The consequence is a further intensification of nationalist sentiment inside China. Chinese online discourse already reflects this shift, with many voices arguing that the situation now presents an ideal opportunity to “punish” Japan militarily.

Under such domestic pressure, China’s leadership will find its room for manoeuvre sharply constrained. Any attempt at de-escalation risks being portrayed as capitulation on historical and sovereignty issues. Takaichi hoped that irreversibility would compel pragmatic engagement; the more likely outcome is the opposite: the stronger her mandate, the less Beijing can afford to retreat.

The most dangerous psychological combination: hatred coupled with contempt

What truly amplifies the danger is not hostility alone, but the psychological structure underpinning it.

Within China, prevailing perceptions of Japan combine two volatile elements. On the one hand, memories of Japanese aggression 80 years ago remain a powerful source of moral mobilisation. On the other, Japan is widely seen as no longer a peer competitor — militarily, economically or strategically. Japan is portrayed simultaneously as morally culpable and materially weak.

History shows that hatred paired with contempt is far more likely to produce war than hatred paired with fear. It diminishes respect for consequences and reinforces the illusion that force can be applied decisively and controllably — that the opponent can be “taught a lesson” without unacceptable costs.

Institutional and symbolic escalation

Within Japan, electoral authorisation is likely to translate rapidly into institutional action. Takaichi will probably push for constitutional revision; even if formal amendment proves difficult, the pacifist framework will be hollowed out in practice. The Self-Defense Forces may be renamed a National Defense Force, the non-nuclear principles abandoned, and offensive capabilities expanded. These are questions of timing, not direction.

At the same time, Takaichi may choose to visit Yasukuni Shrine as prime minister, revise history textbooks and further strengthen diplomatic and military postures aimed at China. Even one or two such moves would be sufficient to lock Sino-Japanese relations into a hardened adversarial state — rather than forcing China to “adapt to reality”.

Towards an irreversible military confrontation

Once Japan inevitably intervenes in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea — and once the US chooses acquiescence over restraint — China will interpret Japanese involvement as a dual violation of historical memory and core sovereignty. At that point, Sino-Japanese relations will no longer resemble strategic competition, but direct security confrontation within shared operational space.

In such a structure, a military standoff will not be the product of any single actor’s intention. It will be the outcome of mutually reinforcing miscalculations.

In such a structure, a military standoff will not be the product of any single actor’s intention. It will be the outcome of mutually reinforcing miscalculations. The remaining uncertainty lies only in where the first clash occurs — and whether anyone will still possess the authority or credibility to step on the brakes.

If Cold War rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union was defined by restraint, East Asia today appears to be entering an era in which all sides are busy preparing moral and political justifications for conflict. That is why the region may now be approaching its most dangerous moment since the Cold War ended.