Russia 'looks East': Surging logistics and trade flows across China-Russia border

With China-Russia trade leaping many-fold since Russia's invasion of Ukraine, both sides have forged stronger cross-border transport and freight links, says US academic Chen Xiangming. However, this comes with challenges, due to Russia's historical orientation toward Europe and severely underdeveloped Far Eastern regional and local economies.

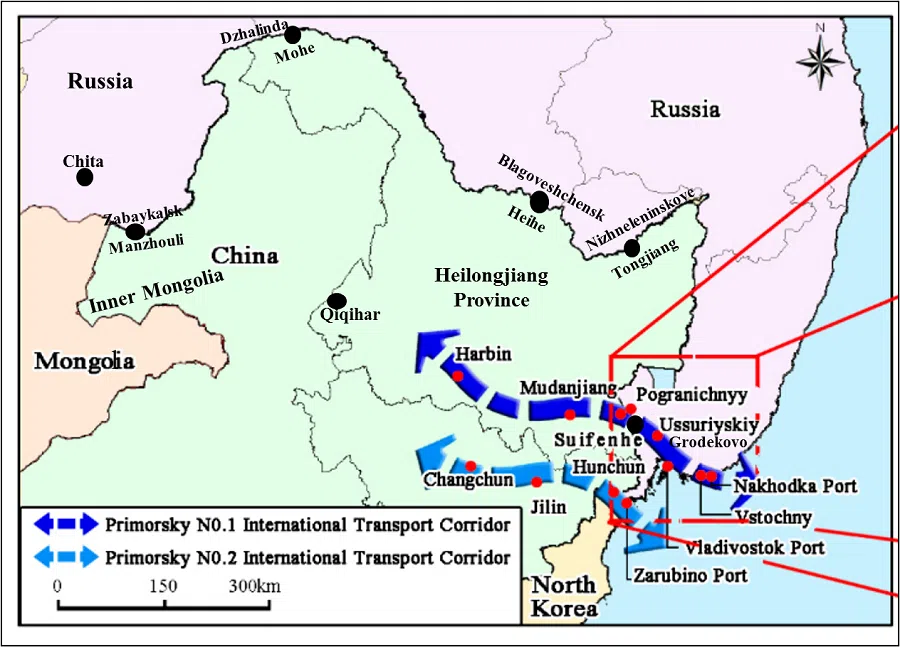

In June 2022, four months after Russian military trucks carrying soldiers rolled across the border to invade Ukraine, the first freight truck carrying cargo crossed a new bridge between the Chinese border city of Heihe and its Russian counterpart of Blagoveshchensk on the Amur River (see map).

Later in 2022, the first freight train crossed the new Tongjiang-Nizhneleninskoye bridge, followed by the launch of container trains in July 2023. These new transport links across the eastern China-Russia border contrast sharply with the battle-ruined borderlands between western Russia and eastern Ukraine.

If the war in Ukraine represents the new (and older) geopolitical reality facing European Russia and the eastern Europe, the new cross-border shipping links between China and Russia reflect a new geoeconomic landscape at the eastern end of Eurasia where the "no-limits" partnership forged by Presidents Xi and Putin has removed some of the historical tension and geographic barriers across the long, remote, and largely rural and underdeveloped borderland spanning the two countries.

This enhanced cross-border regional cooperation reveals the rapidly growing China-Russia trade, especially since the Ukraine war and US-led sanctions on Russia.

The scale and speed at which China-Russia trade has grown masks its unbalanced composition.

Surging Sino-Russia trade

In 2021, China-Russia trade reached US$147 billion. It jumped to US$190 billion in 2022, 29.3% over the previous year. In the first five months of 2023, China-Russia trade reached US$93.8 billion, a 41% increase over the same period in 2022 and an 85% rise over the first five months of 2021.

To put this in perspective, China-US trade amounted to US$690 billion and China-EU trade US$850 billion in 2022, respectively. While China-Russia trade is less than one-third of China's trade with the US and a quarter of its trade with the EU, it has soared since 2021 relative to the declines in both China-US and China-EU trade through 2023.

China's economic relations with Russia vs the US and EU are trending in opposite directions along the trajectories of geopolitical alliance and geoeconomic cooperation versus great-power competition and partial decoupling.

The scale and speed at which China-Russia trade has grown masks its unbalanced composition. The bulk of Russia's exports to China is discounted gas and oil, which hit a record in May 2023. In the opposite direction, machinery and mechanical appliances account for 38% of Chinese exports to Russia. In the first four months of 2023, this category grew by 43% and 59% over the same periods of 2022 and 2021, respectively.

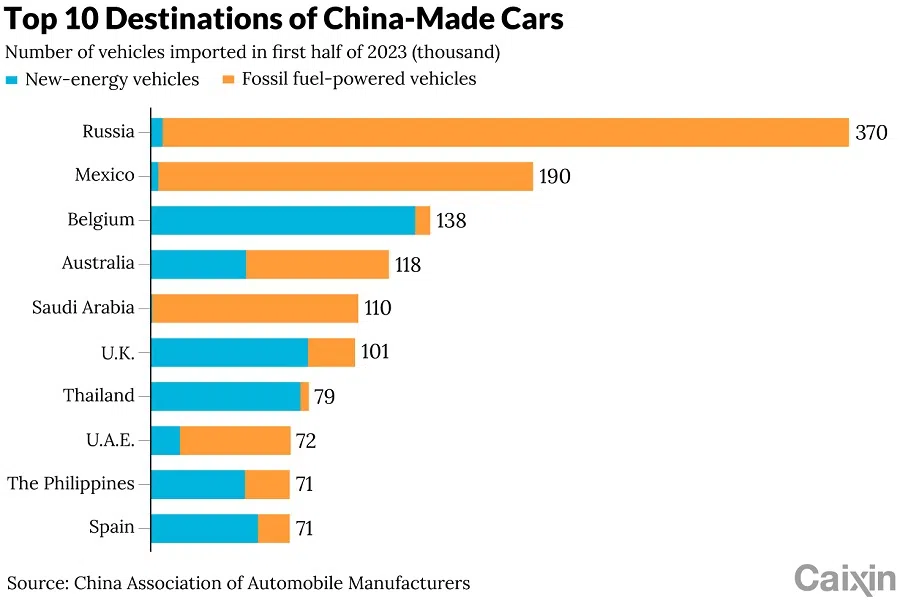

More noticeably, Western sanctions forced European, Japanese and Korean automakers to leave Russia and led China's automotive exports to fill the vacuum. In the first half of 2023, China sold around 370,000 vehicles including electric cars to Russia (chart) worth US$4.6 billion, up five times over 2022. China accounted for almost 70% of Russia's vehicle imports relative to only 10% in 2021.

... more of China's Russia-bound cargo on freight trains has flowed east to enter Russia from Manzhouli in the Inner Mongolia Region and Suifenhe in Heilongjiang province...

While the bulk of China's growing exports to Russia go by sea, an increasing amount has moved overland on the China-Europe freight train through Kazakhstan before joining the Trans-Siberian Railway inside Russia to terminate in and near Moscow. And almost 80% of the west-bound freight trains cross the two small border logistics hubs of Alashankou (Alatau Pass) and Horgos on the China-Kazakhstan border, with around 40,000 and 100,000 people, respectively.

More recently, however, more of China's Russia-bound cargo on freight trains has flowed east to enter Russia from Manzhouli in the Inner Mongolia Region and Suifenhe in Heilongjiang province, with the newly opened Tongjiang land port beginning to clear a small number of freight trains while a limited number of freight trucks cross the Heihe-Blagoveshchensk bridge (map).

As more of China's exports to Russia flow toward and through newly built and improved border logistics openings, it has altered Russia's perception and handling of its Euro-centric relationship...

Shifting border and bilateral dynamics

This eastward turn has also been joined by the existing sea-rail inter-modal shipping links to the largest commercial port of Vladivostok in the Russian Far East.

On 19 August 2023, the Russian Far East Shipping Co (FESCO) moved 300 tons of containerised sea fish (pollock) from Vladivostok through the railway station at Grodekovo (Pogranichny) into the Chinese border city of Suifenhe where the containers were carried on to Harbin, the capital city of Heilongjiang and the region's largest city with 6.7 million people (map), on a freight train with cold-chain wagons. This trip across a cross-border shipping corridor took just 2.5 days.

During the first half of 2023, the Suifenhe land port handled 416 freight trains and 41,000 containers, with a year-on-year growth of 11.5% and 18.4%. Earlier on 1 August, a freight train loaded with vehicles on 55 container wagons for Russia departed the city of Changsha, Hunan province and passed the Tongjiang border crossing on its way to Moscow along the Trans-Siberian Way.

As more of China's exports to Russia flow toward and through newly built and improved border logistics openings, it has altered Russia's perception and handling of its Euro-centric relationship with its far-flung border regions and cities in the Far East.

As Franck Billé and Caroline Humphrey documented in their recent book On the Edge, Russia has kept a historical hypercentralised hierarchy - "an administrative-territorial monster"- that radiated security-oriented controls from Moscow out toward its small Siberian and Far Eastern cities and towns bordering China. This persistent policy accounted for the lagged construction and severe lack of transport infrastructure leading Russia's Amur Highway and Trans-Siberian Railway to run some 35 to 50 km away from the border, with no extended roads to such small border towns as Dzhalinda and Nizhneleninkoye.

Despite and because of Russia's "pivot to the East" policy in 2008, Moscow has only slowly upgraded its logistics facilities bordering Northeast China. For example, Russia is starting to rebuild a dilapidated and idle freight railway of 68 km to connect to the planned Dzhalinda-Mohe rail bridge (map), which would become another freight rail crossing after the new Tongjiang- Nizhneleninskoye bridge.

... Russia is disadvantaged in linking and trading with China across their border due to its historical orientation toward Europe and severely underdeveloped Far Eastern regional and local economies.

Russia has strengthened cross-border economic cooperation with China in response to two pressures. Mired in the war with Ukraine may accelerate Russia in "Looking East" toward Pacific Asia for untapped opportunities linked with China's Belt and Road Initiative over the past decade. Western sanctions also push Russia to fall more deeply into China's embrace via their "no limits" partnership, which easily encompasses more cross-border trade.

Yet given its less favourable economic position in partnering with China, Russia is disadvantaged in linking and trading with China across their border due to its historical orientation toward Europe and severely underdeveloped Far Eastern regional and local economies. This will stick around as the key asymmetry in China-Russia cross-border economic cooperation.

*The author, who studies the relationship between the BRI and cities and has travelled through a number of Silk Road cities across Eurasia, is using this essay to reconnect with his earlier work on the borderlands spanning China, North Korea, and the Russian Far East in the 1990s and update it to recent developments.

Related: Back to the future: Trade routes from the Silk Road(s) to the BRI corridors | China's auto exports belie roadblocks to conquering Europe and US | India, Russia and the Northern Sea Route: Navigating a shifting strategic environment | Wagner's failed mutiny and China-Russia relations: Not weakness but strength | China strengthens its influence in Central Asia as Russia looks on