Can youths transform struggling northeast China? [Eye on Dongbei series]

In China’s northeast, the “transition generation” (those born between 1950 and the 1960s) faced major challenges in the shift from a planned to a market economy, which disrupted their careers and fostered feelings of powerlessness and fatalism. As demographics shift and the needs of young people grow, how will the region adapt? Wen Xie, an academic and Dongbei native, explores this question.

(Photos and graphics provided by the author unless otherwise stated.)

Northeast China, Dongbei (东北) in Chinese and historically referred to as Manchuria, was among the first in China to undergo industrialisation and urbanisation before World War II, particularly during the Japanese occupation.

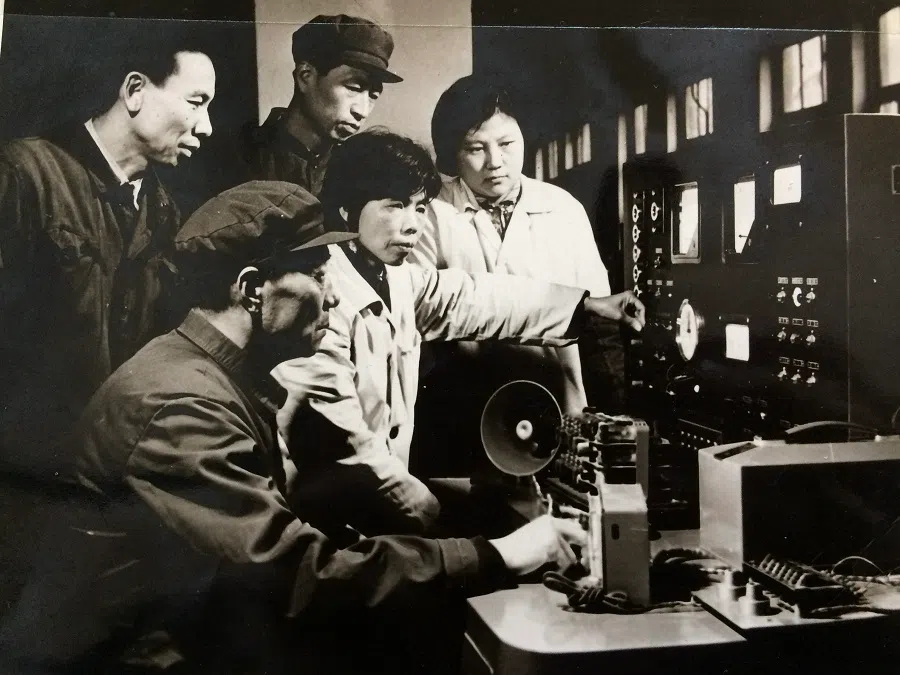

Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Dongbei maintained its status as a crucial industrial hub for the nation. Due to its significant contributions to the country’s industrial development, Dongbei has been affectionately termed the “eldest son of the People’s Republic of China”, underscoring its pivotal role in China’s economic history.

The GDP share of the three northeastern provinces (Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang) has fallen from 13.34% in 1978 to 4.8% in 2023.

The region’s economic performance has been underwhelming since the onset of market reforms. The GDP share of the three northeastern provinces (Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang) has fallen from 13.34% in 1978 to 4.8% in 2023. Over the past decade, the GDP growth rates for these provinces have experienced instances of decline, further underscoring the economic challenges they confront.

The Chinese rust belt

Around the turn of the 21st century, Dongbei experienced massive layoffs during a new wave of state sector reforms known as “grasping the big and letting go of the small” (zhua da fang xiao 抓大放小). The widespread closure of factories in Dongbei has drawn comparisons to the American rust belt.

Historically a hub for manufacturing, steel making and coal production, the rust belt in the US suffered a sharp industrial decline, resulting in widespread unemployment, increased poverty, urban decay and notable population loss. These similarities have earned Dongbei the nickname “the Chinese rust belt”.

Government efforts to revitalise Dongbei have been unwavering. Since the issuance of an official revitalisation plan in October 2003, the central government has prioritised rejuvenating this old industrial base. Over the past 20 years, it has released four major policy documents and hundreds of supportive measures, alongside frequent visits by central leaders to the northeast to provide guidance and encouragement, underscoring their commitment to the region’s development.

Dongbei is often portrayed unfavourably in the media, with locals stereotyped as “lazy”, “conservative”, “dependent” and “not modern”.

Despite extensive revitalisation efforts, Dongbei’s economic performance has remained sluggish, especially compared to the dramatic growth seen elsewhere during the “China miracle”. In 2003, the combined GDP of the three northeastern provinces was 73% of Guangdong’s and 168% of Henan’s. By 2023, however, Dongbei’s total GDP had dropped to just 44% of Guangdong’s and was merely comparable to Henan’s. This decline underscores the region’s struggle to keep pace with the rapid economic advancements transforming other parts of the country.

Dongbei is often portrayed unfavourably in the media, with locals stereotyped as “lazy”, “conservative”, “dependent” and “not modern”. Many commentators view market transformation as a natural process and, given Dongbei’s underperformance compared to other regions, particularly the southeast, suggest that the local population lacks the inherent “genes” for market-driven growth.

Labelling a region as culturally unfit for a new era is not only counterproductive but also overlooks the need for a thorough reassessment of the complex socioeconomic dynamics at play. A superficial understanding of society might well explain the shortcomings of revitalisation efforts. To truly grasp the current state of Dongbei and to devise effective strategies for its future development, a detailed exploration of the social dynamics within the region is essential.

The ‘transition generation’

Market transition did not occur in a vacuum or on a blank canvas but transpired within a local population rooted in the past. Understanding Dongbei’s social transformation requires exploring the life experiences of individuals during the shift from a planned economy to a market-oriented era, which saw the dissolution of the danwei (单位 work unit) society.

... the radical state sector reforms of the 1990s left many laid off in their forties and fifties.

Individuals most affected were members of the “transition generation”, born between 1950 and the 1960s and commonly known as the “baby boomers”. This cohort faced a significant employment crisis in Dongbei in the late 1970s and early 1980s. State-owned enterprises played a crucial role in mitigating these challenges, effectively absorbing a large portion of this generation into their workforce.

Upon entering socialist factories, members of this generation expected a comprehensive welfare system that promised job security and benefits from cradle to grave. They anticipated devoting their entire working lives to these jobs. However, the radical state sector reforms of the 1990s left many laid off in their forties and fifties.

National propaganda promoted a new market-based ideology, encouraging former “iron rice bowl” workers to embrace the market economy and become entrepreneurs. Reality, however, was harsh for the transition generation.

Middle-aged workers found themselves outcompeted by younger migrant workers from the countryside and recent college graduates. Consequently, many had to resort to informal and precarious employment, such as street vending, domestic labour and being security guards, to make ends meet.

Disruptions in their career paths hindered their ability to build self-efficacy, diminishing their capacity to control their life trajectories. Consequently, many felt powerless and resorted to fatalism.

Most of the laid-off workers struggled significantly with the challenges of becoming “self-made” and “successful” market actors. Disruptions in their career paths hindered their ability to build self-efficacy, diminishing their capacity to control their life trajectories. Consequently, many felt powerless and resorted to fatalism.

To preserve their dignity, individuals often relied on familiar social relationships and fragmented welfare arrangements. In Dongbei, the emphasis on guanxi (关系 relationships) and prioritising jobs at public institutions were not just remnants of the old “danwei culture”. Instead, these were desperate responses from people navigating an environment where local economic pillars had collapsed and opportunities for economic expansion were scarce.

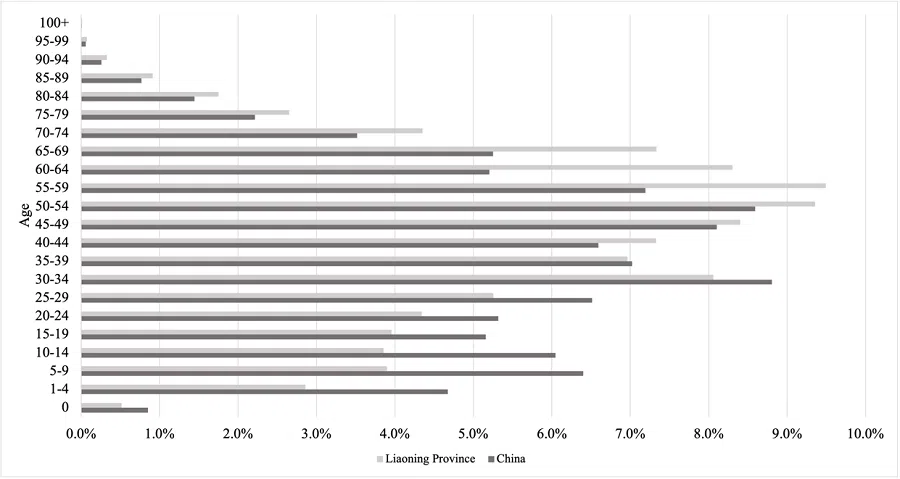

Demographically, the generation remains a pivotal segment in local society. However, it is essential to recognise that the social composition is not static but is continually evolving. Individuals adapt to external changes and redefine their roles within society.

As older generations pass away and younger ones mature, the demographic makeup naturally shifts. This dynamic demographic landscape underscores the urgent need for adaptable economic and social policies that respond effectively to these changes.

Dongbei’s future

Based on the generational makeup of society, we can identify diverse solutions to the challenges confronting Dongbei. Beyond the prevalent top-down, industry-centric revitalisation strategies, it is crucial to improve the region’s appeal to younger demographics. Enhancing opportunities for the youth can help alleviate pension deficits, potentially reverse the trend of an ageing labour force, and infuse the local economy with vitality and innovation.

Recent years have seen some intriguing developments unfold. The exceptionally low housing prices in areas like Hegang have drawn a surge of young people from beyond the region. The energy and activities of these newcomers and local youth have injected fresh vitality into the local community. This burgeoning youth movement is actively establishing new artistic spaces, producing films, writing novels, and preserving industrial legacies, significantly enriching the cultural and artistic landscape of Dongbei.

If industrial revival efforts falter, why not place our trust in the young?