Surveillance, pressure, silence: Why China’s youth are falling apart

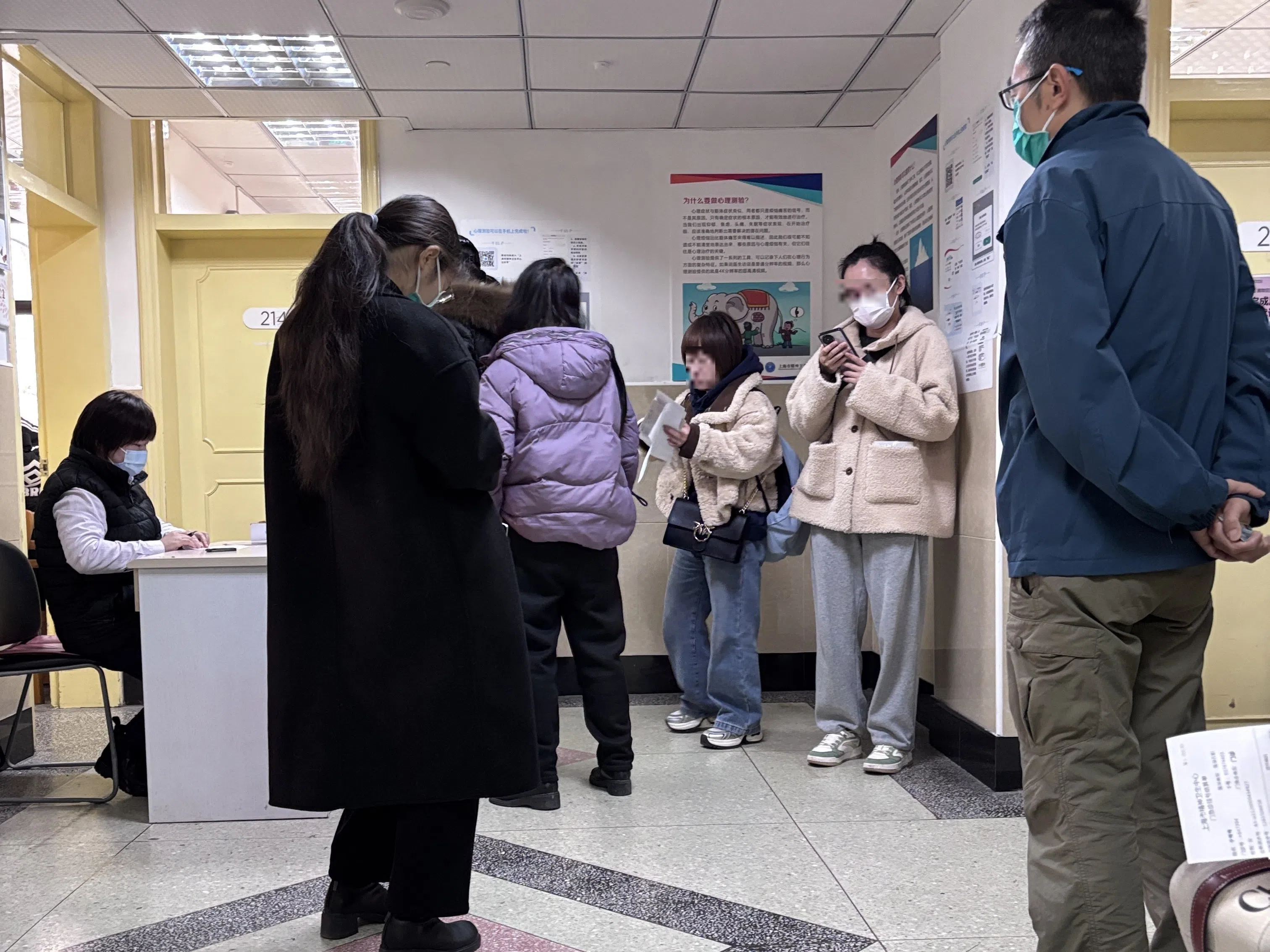

Spending at least the first two decades of their life in academics and all sorts of enrichment classes to get ahead, Chinese youths live in a high-pressure environment that is jeopardising their mental health. Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Li Kang uncovers the dark underbelly of Chinese youths’ lives.

“A classmate just stopped coming one day. Then, after a while, another disappeared. In my middle school class of over 30 students, this happened to around ten people.”

Sitting across from me, Xiaoyue recounted the story calmly, as if such disappearances were entirely normal. What she was referring to were the three most common mental health conditions affecting Chinese youth: depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder — or, in many cases, a mix of both.

Absurdity and breaking point

Before meeting Xiaoyue, my understanding of mental health among Chinese youth came mostly from reports. According to the National Depression Blue Book released in 2023, 95 million people in China suffer from depression — nearly one-third of them minors under 18.

But Xiaoyue’s story revealed the silent, often hidden struggles facing China’s post-2000 generation.

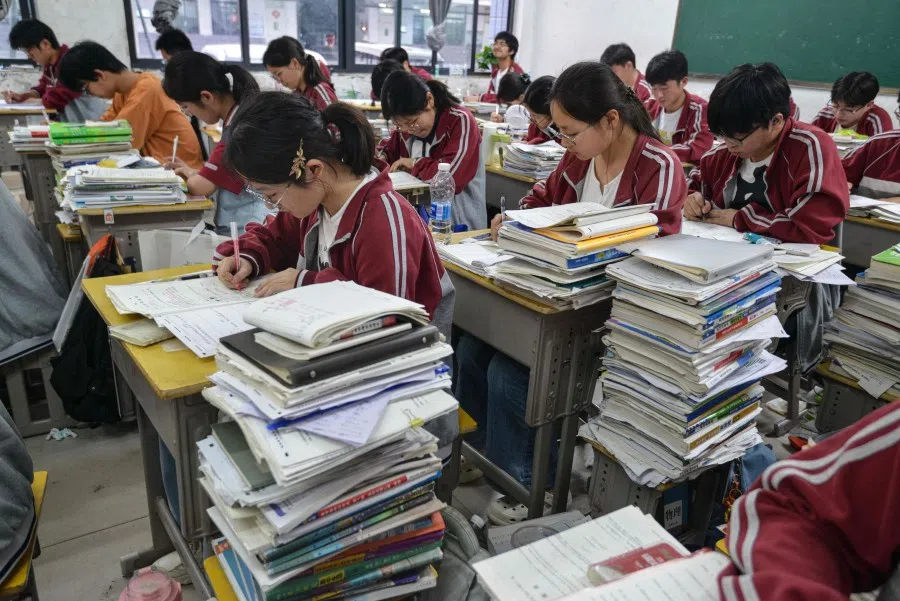

Xiaoyue was born in a wealthy province in eastern China. Now in her junior year of university, she is preparing to apply for graduate school. For the past 20 years, her life has revolved almost entirely around academics. Like many Chinese students, she spent every school break before the college entrance exam (gaokao) at cram schools.

What Xiaoyue found even harder to accept were some of the school’s absurd regulations. For example, in high school there was the “passionate morning reading”, which required students to read aloud with an almost frenzied enthusiasm.

From kindergarten onwards, she joined classes that taught idioms, classical poetry and mental arithmetic. After moving up to primary school, in addition to Olympiad math and English conversation with foreign teachers, she also had to pick up a few showcase talents. By the time she reached middle and high school, her weekends were packed with tutoring for various subjects.

Academic pressure was one thing. What Xiaoyue found even harder to accept were some of the school’s absurd regulations. For example, in high school there was the “passionate morning reading”, which required students to read aloud with an almost frenzied enthusiasm. To monitor the volume, the classrooms were even equipped with decibel meters, and only readings above 90 decibels were considered a “pass”. Classes that failed to meet the standard were punished by having to make up the reading session during meal times.

In Xiaoyue’s view, this morning reading where the loudest won was utterly meaningless. “All I got was a sore throat, aching ears and a muddled head. I couldn’t hear or remember any of what was read,” she said.

After long hours in the classroom, Xiaoyue often felt breathless. Some classmates, unable to cope with the pressure, even resorted to self-harm. She shared, “Once, a classmate hurt himself in the classroom. The student sitting next to him was so triggered that it caused their depression to flare up. A week later, the boy came back to class with bandages wrapped around his wrists and went on studying.”

Each classroom is equipped with three surveillance cameras. An artificial intelligence system automatically detects who is absent and who is using their phone during class.

Another time, a high-achieving girl broke down completely because she didn’t earn the highest score for an exam. Xiaoyue said, “I heard her piercing screams in the hallway — it went on for two hours. She must have really reached her breaking point.”

No relief in sight

Would things get better in university? Xiaoyue shook her head. She said that today’s universities are no longer ivory towers of freedom, but more like an “extended version of high school”.

Not only do students have to attend morning and evening self-study sessions, but if they have no classes on weekdays, they have to request permission to leave campus. If they stay out overnight, they have to call their counsellor to explain why. The dormitory monitor also conducts nightly roll calls, and if the names don’t tally, the students involved face anything from a “talk” to disciplinary punishment.

Each classroom is equipped with three surveillance cameras. An artificial intelligence system automatically detects who is absent and who is using their phone during class. The lectures are also automatically recorded and uploaded to the school website, placing teachers under constant monitoring — “what they can say in class is becoming increasingly limited”.

The library is no longer a sanctuary for the pursuit of knowledge; it is almost impossible to find anyone genuinely absorbed in reading. Ninety-eight percent of students are preparing either for graduate school entrance exams, civil service exams, or overseas tests like IELTS and TOEFL. Xiaoyue said, “It feels as if there are only a few life paths, and once you pick one, you have no choice but to charge forward.”

“I’ve worked so hard since I was a kid. It’s really exhausting, but I can’t stop. It feels like all the effort of the first half of my life has been for the sake of securing a place in graduate school. How could I give that up easily?” — Xiaoyue, a university student

Xiaoyue chose what seemed to be the safer option — guaranteed admission to graduate school — but in reality, the level of competition is no less fierce than in other paths. Beyond evaluating academic performance, she is expected to file patents, publish papers in core journals, and maintain an impossibly high GPA.

She said, “You can’t afford to slip up in a single course, or your ranking will drop immediately. If you fall out of the top three, you’re no longer considered a promising candidate for guaranteed admission.”

Thinking about the future fills Xiaoyue with a deep sense of helplessness. “I’ve worked so hard since I was a kid. It’s really exhausting, but I can’t stop. It feels like all the effort of the first half of my life has been for the sake of securing a place in graduate school. How could I give that up easily? Everyone is being pushed forward, and no one dares to stop, so we can only keep running.”

Government intervention

Xiaoyue’s experience reflects what many Chinese youths go through today. They grow up under intense academic pressure and within tightly controlled school environments, driven by meritocracy to keep running forward on a one-way track.

Closed-off study and social circles — ostensibly to keep students safe — have in fact quietly deprived young people of the space to explore within themselves and regulate their emotions. With no outlet for their feelings, psychological issues accumulate like an undercurrent, eventually becoming a collective hidden pain of an entire generation.

Yet in practice, many schools still treat mental health problems as isolated incidents, attributing them to an individual’s “inability to handle pressure” or “not having enough time outdoors”, rather than examining the systemic pressures and strains.

In a government work report released in March this year, mental health issues were given more prominence. In terms of young people’s mental health, the authorities said, “We will vigorously carry out physical education activities in schools, ensure access to mental health education, and show concern for the physical and mental wellbeing of students and teachers.”

Yet in practice, many schools still treat mental health problems as isolated incidents, attributing them to an individual’s “inability to handle pressure” or “not having enough time outdoors”, rather than examining the systemic pressures and strains. Mechanisms for effective psychological intervention remain absent, and having the full weekend off that students have long been calling for has yet to be fully implemented.

When discussing issues such as youth employment or academic anxiety, society must also look at these unseen corners. Mental health has never been just an “emotional issue”; it is about whether a generation can grow up sound and whole, and whether a society is truly willing to take its future to heart.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “中国青年隐秘角落的痛”.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)