AUKUS: A reflection of ASEAN's inability to cope with China's rising assertiveness?

Southeast Asian responses to the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) technology-sharing agreement, which aims to provide Australia with nuclear-powered submarines, have varied considerably, from warnings that the agreement could trigger an arms race or undermine regional stability to implicit support. While concerns over arms racing and nuclear proliferation are seen by some as being overblown, AUKUS is a response to China's rapid military modernisation and assertive behaviour in the maritime domain. Thus, AUKUS can be seen as a wake-up call to ASEAN that it needs to be more proactive on security issues and cannot take its centrality for granted.

On 15 September 2021, Australia, the UK and the US announced a three-way technology-sharing agreement called AUKUS. The primary purpose of AUKUS is to provide Australia with nuclear-powered submarines, but it also includes a commitment to jointly develop other technologies such as quantum computing, artificial intelligence and other undersea capabilities. According to a joint statement, the deal underscores the three countries' commitment to deepen diplomatic, security and defence cooperation in the Indo-Pacific so as to meet the "challenges of the twenty-first century".

China warned that AUKUS would "undermine regional peace and stability, aggravate arms race(s) and impair international nuclear non-proliferation efforts". Southeast Asian responses varied. Malaysia and Indonesia expressed concerns about the risks of arms racing, while Singapore, Vietnam and the Philippines were generally more accepting of the arrangement.

AUKUS should be seen as an attempt to address the perceived imbalance in the regional balance of power stemming from China's military build-up and assertiveness. More pertinently, the advent of AUKUS and other US-led initiatives such as the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad, linking the US, Australia, India and Japan), underscores the fact that extra-regional powers are seeking minilateral options outside the multilateral framework led by ASEAN.

Southeast Asian responses

Malaysia

Malaysia's reaction to AUKUS has been predictable and in accordance with its long-standing shibboleths on regional security. In a phone call with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, and reiterated in a statement released the next day, Malaysian Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob expressed concern that the new security arrangements could be a catalyst for a nuclear arms race in the region and might provoke some countries to act aggressively, especially in the South China Sea.

In raising these concerns, he stressed Malaysia's commitment to Southeast Asia as a Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality (ZOPFAN) and the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapons Free Zone (SEANFWZ), as well as Malaysia's stance on not allowing nuclear-powered vessels to enter its territorial waters.

Subsequently, Defence Minister Hishammuddin Hussein and Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah issued statements of their own, echoing the prime minister's disquiet. In an extraordinary move, Hishammuddin announced he would pay a working visit to China for consultations. Former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad also weighed into the debate, warning that AUKUS increased the risk of great power conflict in Southeast Asia.

Malaysia's concerns are not without merit but are overblown. AUKUS is designed to provide Australia with nuclear-powered submarines - not nuclear-armed submarines.

Australia has stated categorically that it does not intend to acquire nuclear weapons and remains committed to nuclear non-proliferation. However, Australia's acquisition of nuclear-propelled submarines may set a precedent for Japan and South Korea if one day they decide to go on the same path.

In recent years, successive Malaysian governments have warned that the increased presence of foreign warships in the South China Sea is destabilizing and risks triggering a military confrontation. Malaysia has stood its ground on its territorial claims and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) rights, rejected China's nine-dash line claims and retained close defence links with the US, Australia and, through the Five Powers Defence Arrangements (FPDA), the UK.

Given China's assertive behaviour in Malaysia's EEZ, it is doubtful the country's national security establishment is as concerned about AUKUS as Malaysian politicians appear to be.

Hishammuddin's announcement that he would visit China to discuss AUKUS came under criticism from the opposition Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition which, although sharing the Prime Minister's concerns, felt that through this act, Malaysia could be perceived as taking sides.

With regard to ZOPFAN and SEANFWZ, the former is a dead letter while the latter is not open for Australia to sign.

A Malaysian initiative endorsed by ASEAN in 1971, ZOPFAN was meant to eliminate major power rivalry in Southeast Asia during the Cold War. Although the concept remained in the ASEAN lexicon post-Cold War, in practice, member states have established forums to engage external powers on regional security issues including the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in 1994, the East Asia Summit (EAS) in 2005 and the ASEAN Defence Ministers' Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus) in 2010.

SEANFWZ, adopted by ASEAN in 1995, prohibits member states from possessing nuclear weapons. It includes a protocol that is open to accession by the five recognised nuclear-armed states (US, Russia, UK, France and China) but none of them have signed it.

Hishammuddin's announcement that he would visit China to discuss AUKUS came under criticism from the opposition Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition which, although sharing the prime minister's concerns, felt that through this act, Malaysia could be perceived as taking sides. He may have taken these criticisms on board, instead holding a video call with Chinese Defence Minister General Wei Fenghe. In a tweet, Hishammuddin did not mention whether AUKUS had been discussed.

Indonesia

In a statement on 17 September 2021, Indonesia's foreign ministry said it "cautiously" took note of AUKUS, and stressed that Jakarta was "deeply concerned" over the "continuing arms race and power projection in the region".

Indonesia called on Australia to continue meeting its nuclear non-proliferation obligations, and called on Canberra to maintain its commitment towards regional peace and security in accordance with the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC) to which Australia is also a "High Contracting Party".

A fuller assessment of AUKUS came from senior Indonesian diplomat Abdul Kadir Jailani. Writing in the Jakarta Post, he echoed his government's assessment, but noted that no international norm appeared to have been violated. He added that "deeper conversations" about AUKUS would help build mutual trust, confidence and diplomacy.

On deeper examination, Indonesia's response is less negative than originally perceived.

Concerns about arms racing and power projection need to be set in proper perspective. It should be noted that Indonesia's fears about such developments - worded as "the continuing arms race and power projection" (italics added) - refers not only to the three AUKUS partners, but all regional states, including China.

In addition, to argue that AUKUS would precipitate an arms race is an inversion of cause-effect logic. It is clear that AUKUS is a direct result of China's "increasingly provocative actions". Australia's Defence Strategic Update in 2020 noted that Canberra's strategic environment had deteriorated more quickly than anticipated since its 2016 defence white paper. While there were few explicit references to China, it was clear that Beijing's military build-up was the main focus of Canberra's concerns.

The 6.4% increase in China's defence spending in 2020 (US$9 billion in real terms) is more than the combined real increase in Indo-Pacific regional states in that year. China's economic coercion of Australia - including the imposition of high tariffs on Australian products - after Canberra called for an inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus also played a part in Australia's decision to strengthen its power projection capabilities.

On deeper examination, Indonesia's response is less negative than originally perceived. One Indonesian analyst noted that Indonesia's "tepid response" is "noticeable". He added that past US-backed initiatives to deter China - for instance, the Obama administration's pivot to Asia - incited negative reactions from several ASEAN countries. Yet Indonesia's reception to AUKUS has been more nuanced.

The Philippines

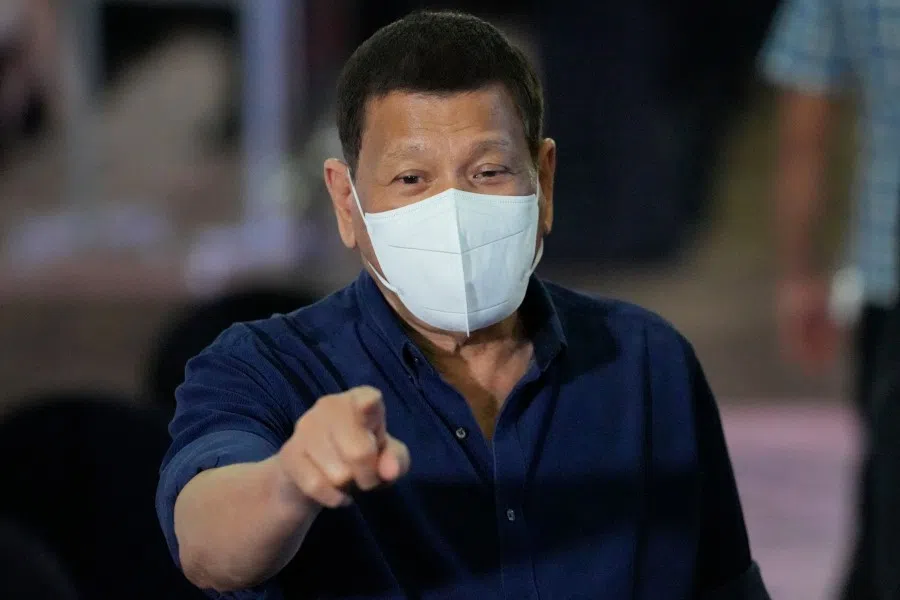

The responses from the Philippines brought into sharp relief serious divisions within the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte over national security issues.

Since Duterte took office in 2016, US-Philippines relations have been under strain due to his pledge to "divorce" America and seek closer relations with China and Russia. This has resulted in the scaling back of some bilateral defence engagements (compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic) and Duterte's threat to terminate the 1999 Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) - a threat that was only withdrawn in July during a visit to Manila by US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin.

It was no surprise, therefore, that following the AUKUS announcement, presidential spokesman Harry Roque said that Duterte was worried the pact could trigger a "nuclear arms race".

The two ministers' support for AUKUS reflects the Philippine national-security establishment's support for the US alliance system and growing concerns about China's assertive policy in the South China Sea.

Prior to Roque's statement, however, two key members of Duterte's cabinet had already come out in full support of AUKUS. Defence Secretary Delfin Lorenzana stated it was Australia's right to improve its defence capabilities as the Philippines was also doing to protect its territories.

Foreign Minister Teddy Locsin Jr. released an erudite statement which welcomed the establishment of AUKUS and made three key points. First, ASEAN members, singly and collectively, lack the military capabilities to ensure peace and security in Southeast Asia. Second, with the region's main balancer, the US, geographically distant, the strengthening of Australia's power projection capabilities would help maintain the regional balance of power and enable Canberra to better respond to threats facing the region. Third, as Australia is not seeking to acquire nuclear weapons, AUKUS does not violate SEANFWZ nor Canberra's commitments to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) or ASEAN centrality.

The two ministers' support for AUKUS reflects the Philippine national-security establishment's support for the US alliance system and growing concerns about China's assertive policy in the South China Sea.

Singapore

Singapore's reaction to AUKUS has been relatively measured, and reflects the country's support for the deployment of US military forces in the region. After being briefed on AUKUS by his Australian counterpart Scott Morrison, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong noted the longstanding relations between Singapore and Australia. He expressed hope that AUKUS would contribute constructively to the peace and stability of the region as well as complement the regional architecture.

From a wider perspective, AUKUS was not really the "centrepiece of concern", and the bigger question was the management of US-China relations.

Speaking to reporters subsequently, Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan expressed the same sentiments. He noted that Singapore had longstanding relationships with all three AUKUS members, and that such "large reservoirs of trust and alignment" were "very helpful". This meant that Singapore was not "unduly anxious" about the new developments.

The key point, the minister said, was that AUKUS was "part of a larger geostrategic realignment"; Singapore had to take it in its stride and make sure it did not end up in an "unviable or dangerous" position. From a wider perspective, AUKUS was not really the "centrepiece of concern", and the bigger question was the management of US-China relations.

Singapore's position is not unexpected. The island republic has always sought to facilitate a balance of power where no major power dominates; it also seeks to involve major powers, in particular the US, in its security. In this context, AUKUS, in the face of growing Chinese military power and assertiveness, would serve as another plank in maintaining and restoring the regional balance of power.

Vietnam

Vietnam's approach to AUKUS largely mirrors Singapore's, underscoring the two countries' big-picture approach in appraising regional realities. A Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson noted that all countries should work towards the same goals of peace, stability, cooperation and development in the region. The spokesperson stressed that the nuclear energy used for Australia's new submarine fleet must be used for peaceful purposes, serve socio-economic development, and ensure safety for humans and the environment.

Vietnam's reaction is not unexpected. Hanoi's long-running dispute with China in the South China Sea has led it to pursue stronger relations with the US, as well as other Quad countries. While Hanoi has not expressed open and public support for the FOIP strategy that is shared by the Quad countries, it has expressed support for FOIP principles, such as the importance of maintaining freedom of navigation and resolving disputes peacefully and in accordance with international law. In essence, Vietnam indirectly supports the Quad and FOIP as they provide Hanoi with a carapace against growing Chinese assertiveness.

Vietnam has also sought to improve relations and defence cooperation with individual Quad members. In September, Hanoi signed an agreement with Japan for the transfer of defence equipment and technology. As a former Vietnamese ambassador put it, US-led groupings such as the Quad are playing an "important role" in countering China's assertiveness. AUKUS, he added, should bring "new confidence" to countries contesting China's excessive maritime claims.

Thailand

As a treaty ally of the US, but also a close partner of China, Thailand responded to AUKUS with characteristic circumspection. Thailand wants to preserve cordial ties with both parties and does not wish to take a position on the trilateral arrangement and risk offending either Washington or Beijing. In any case, the Thai government is preoccupied with domestic political issues and has little bandwidth for regional security issues

Accordingly, there has been no official response from the prime minister's office or the ministries of foreign affairs or defence. Ten days after AUKUS was announced, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-Cha delivered a pre-recorded speech at the United Nations in which he pledged Thailand's support for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (of which Australia is not a signatory) and the NPT. His references to these two treaties could be a sign that Thailand has reservations about AUKUS.

In the absence of a response from the government, the void has been filled by prominent Thai observers who offered contrasting views on this matter. Hyperbolically, journalist Kavi Chongkittavorn has accused the three countries of fuelling an arms race in the Indo-Pacific, provoking tensions with China and forcing regional states to choose sides in the escalating US-China competition. Former Thai Foreign Minister Kasit Piromya stated that no country wanted to be dominated by China and that therefore the US military presence is necessary, and presumably by extension, those of its allies and partners.

The plan would be for the RAN to receive its first nuclear-propelled submarine in the late 2030s or early 2040s.

Developing nuclear weapons 'by the back door'?

Kasit's point is apposite as it applies to Southeast Asia and ASEAN, and underscores the Singaporean and Vietnamese underlying approach to AUKUS: in the face of growing Chinese power, any line of effort that can lead to regional stability is a net positive. Some Chinese commentators recognise that Australia plays a "critical role" in the region; they also view the three-way deal as a sign that countries are willing to come together to push back against Beijing.

With regard to non-proliferation, there are clearly concerns about what AUKUS portends for nuclear non-proliferation in terms of setting a precedent for future proliferation by utilising naval reactor programmes to develop nuclear weapons "by the back door". These concerns are largely misplaced. Although a final decision has yet to be made, the most likely outcome after the 18-month consultation process among the AUKUS members is that Australia will join a UK-led project to design a successor to the Royal Navy's Astute-class nuclear-powered attack submarines.

The British-designed submarines for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) would be constructed in Adelaide, but the nuclear reactors would be built in the UK and installed in Australia as a "black box". British reactors have a lifespan of around 30 years which means Australia would not have to enrich uranium nor refuel the submarines, thus eliminating the risk of nuclear proliferation. The submarines will be armed with US-made Tomahawk cruise missiles and, probably, US-made torpedoes.

Given the limited numbers of both US and UK nuclear-powered submarines, it is unlikely that Australia will lease any from either country, though US nuclear attack submarines could be forward deployed to Australia. Australian submariners would probably train on British submarines.

Starting from the mid-2020s, the operational life of the RAN's current fleet of Collins-class submarines will be extended for 10 years while the nuclear-powered boats are under construction. The plan would be for the RAN to receive its first nuclear-propelled submarine in the late 2030s or early 2040s.

ASEAN centrality in question?

Concerns about AUKUS stem less from the trilateral deal per se, but more from the attendant fears of a loss of regional stability with the projection of US and allied forces into the region amid intensified Sino-US competition.

A case in point was the deployment of US naval forces - including the small carrier USS America - off the coast of Borneo in April 2020. This was in response to a Chinese survey ship, and accompanying coast guard and maritime militia ships, which were shadowing the West Capella, a drillship chartered by Petronas near the outer edge of Malaysia's EEZ.

ASEAN needs to question why AUKUS has happened without its knowledge; one has to ask whether the "centrality" that ASEAN and its partners talk about is "merely lip service". - Nguyen Hung Son, vice-president, Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam

While the US effort has been noted as a decisive effort to confront China and reassure regional states, it has also been argued that America's lack of staying power in the area (the warships left after five days) escalated the situation for Malaysia and only served to "make things worse". In recent years, US freedom of navigation operations to challenge China's excessive maritime claims in the South China Sea have raised the risk of accidental escalation.

Lastly, AUKUS reflects ASEAN's lack of ability to cope with China's increasing assertiveness in the maritime domain, particularly in the South China Sea. ASEAN's concept of inclusive and cooperative security has proved to be inadequate; like the Quad, AUKUS as a balance-of-power entrenchment is a "natural response" to coping with China's maritime expansionism in the region.

The establishment of the EAS in 2011 and the ADMM-Plus in 2010 led to optimism that the region's security architecture would reduce the risks of flare-ups. But more recently, hopes for an effective Asian security architecture has started to dissipate. As Nguyen Hung Son, the vice-president of the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam, has noted, ASEAN needs to question why AUKUS has happened without its knowledge; one has to ask whether the "centrality" that ASEAN and its partners talk about is "merely lip service".

The AUKUS deal, and the Quad and FOIP strategy that precede it, underscore the fact that while ASEAN Dialogue Partners such as Australia, the UK and the US consistently echo the mantra of ASEAN centrality, they do not see the concept as inviolate or sacrosanct amid a fast-changing geopolitical environment. As former Indonesia foreign minister Marty Natalegawa notes, AUKUS is a reminder to ASEAN of the cost of "dithering and indecision" in a fluid strategic environment.

In fact, it has become increasingly apparent that China and the US, while reiterating the importance of ASEAN centrality, have sought to use such reiterations to woo the ten-member grouping to their respective sides, whether it be to the China-centric Belt and Road Initiative or FOIP.

What AUKUS illustrates is that in the face of ASEAN's apparent inability to respond effectively to changes in the geopolitical environment, the three-way deal, as well as the Quad, represent an evolving new Asian security architecture where minilateralism runs parallel to multilateral institutions centred on ASEAN.

Given that AUKUS and the Quad are essentially responses to China's military modernisation and belligerence, ASEAN would need to manage two challenges simultaneously: harnessing the power of such extra-regional initiatives to maintain a balance of power while simultaneously ensuring ASEAN cohesion and relevance in the fraught regional security environment.

This article was first published by ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute as ISEAS Perspective 2021/134 "Southeast Asian Responses to AUKUS: Arms Racing, Non-Proliferation and Regional Stability".

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)