Bali, 1952: Nanyang artists’ search for inspiration

A visit by Nanyang artists to Indonesia in 1952 comes alive with new-found negatives of images taken during the trip, uncovered by Gretchen Liu, writer and daughter-in-law of artist Liu Kang. Writer Teo Han Wue shares his thoughts on the subject after reading Liu’s Bali 1952: Through the Lens of Liu Kang and experiencing the NLB exhibition that accompanies it.

From the 1930s, writers among the Chinese intelligentsia arriving in Singapore began to stress the importance of “Nanyang literature” focusing on life in the tropics rather than being “reduced to a tributary of Chinese culture”.

Art critic Koh Cheng Foo (Marco Hsu), for example, in a series of newspaper articles from 1933 to 1936, which were later collected in a book titled Nanyang Zhi Mei (《南洋之美》The Beauty of Nanyang) about art in Malaya and Singapore, was paying greater attention to “Nanyang colour”.

Lim Hak Tai, the founding principal of the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA), established in 1938, found Singapore’s geographic position and cultural environment favourable to the creation and promotion of art rich with Nanyang characteristics and acting as a bridge between the East and the West.

In his vision for the academy, Lim placed art activity in a context that is shaped by Southeast Asian perceptions, which have come to characterise the works of a group of artists collectively known as the Nanyang artists.

It is in this historical context that one can appreciate even more fully the rich contents of Gretchen Liu’s excellent new book Bali 1952: Through the Lens of Liu Kang, launched recently in conjunction with the exhibition “Untold Stories: Four Singapore Artists’ Quest for Inspiration in Bali 1952” on at the National Library in Singapore until 3 August 2025.

As the late artist Liu Kang’s daughter-in-law, Gretchen stumbled upon a shoebox marked with four bold characters “相片峇厘” (photographs Bali), while going through things left behind in the artist’s Jalan Sedap home in 2016.

Treasure trove of images from a 1952 trip to Indonesia

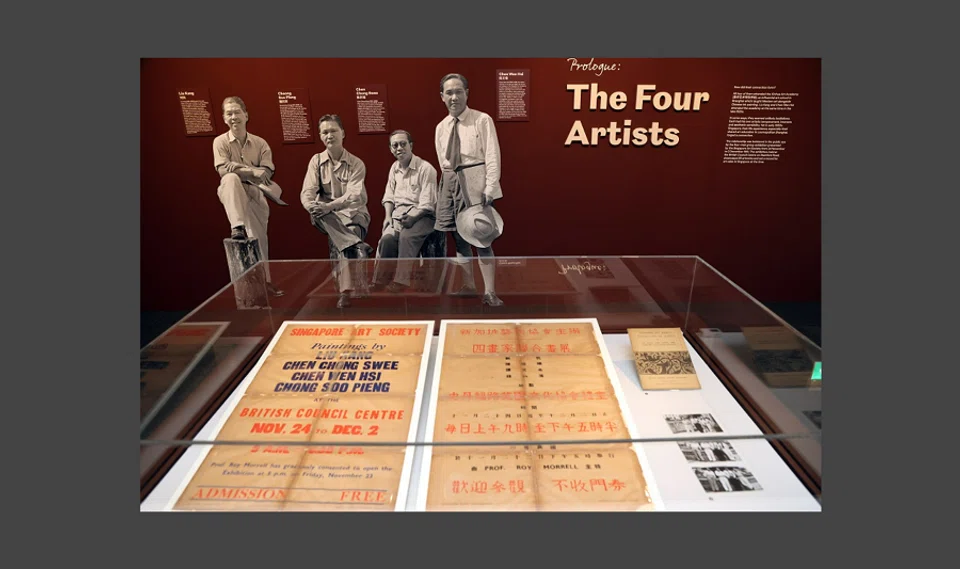

Gretchen Liu, a former journalist, has written many books on Singapore’s visual heritage. This new book by her must be enthusiastically welcomed because it fleshes out the story of the historic Indonesian journey by four China-born Nanyang artists Liu Kang (1911-2004), Chen Wen Hsi (1906-91), Cheong Soo Pieng (1917-83) and Chen Chong Swee (1910-85) in the most authentic and comprehensive way possible.

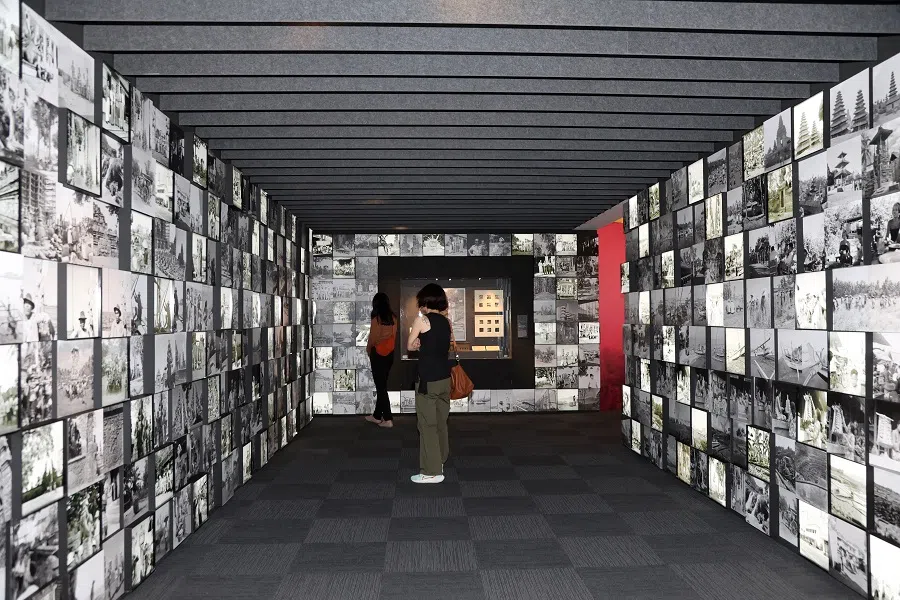

As the late artist Liu Kang’s daughter-in-law, Gretchen stumbled upon a shoebox marked with four bold characters “相片峇厘” (“Photographs, Bali”), while going through things left behind in the artist’s Jalan Sedap home in 2016. It was filled with 6cm x 6cm negatives and prints neatly kept in envelopes clearly labelled in English and Chinese. Four years later she took a closer look at the contents only to realise what an astonishing collection of 1000 negatives she had found.

She selected from these negatives, images of the 1952 trip, which had been left forgotten for decades, for the main part of the book as well as the exhibition it accompanies. The pictures are pieced together with materials such as sketches, paintings, collection of books, letters and diaries to offer a completely fresh and detailed account of the trip for the very first time. The author also made admirable efforts to reach out to families of the other artists for some cross-references.

The book tells a compelling story about the four Nanyang artists’ search for inspiration that took them not just to Bali alone but also Jakarta, Bandung, Bogor, Malang, Yogyakarta, Solo and Surabaya. It clarifies the fuzzy impression created by popular accounts calling their seven-week adventure “Bali trip” as though that was the only place they went.

The substantial 298-page book is an impressive tome with Liu Kang’s aesthetically framed photographs matched by Gretchen’s well-written, meticulously researched and annotated texts suitably illustrated with the artists’ works making it an indispensable reference for museum professionals and art lovers alike.

Their itinerary, we are told, began on 8 June 1952 at Kallang Airport for a flight to Jakarta where they stayed for a week before driving to Bandung for a four-day stay on 15 June. In their original plans they would have toured Java first before getting to Surabaya from which they had hoped to fly to Bali where they would stay for two weeks.

But they re-ordered their route due to the upcoming Aidilfitri holiday leaving the rest of Java till after Bali, where they were to spend almost a month. They took a 13-hour train ride directly from Bandung to Surabaya where they found flight tickets to Bali sold out and ships unavailable. They were left with the option of a car ride, which turned out to be so expensive that they did not feel “it was really worth the money”.

For those of us used to flying direct from Singapore to Bali in under three hours, it must be hard to imagine what an arduous journey the group chose to take from Singapore to Bali back then.

A ‘hair-raising’ journey across the Bali Strait

Fortunately they were introduced by Chen Wen Hsi’s cousin to a Surabaya businessman Lie Tjek Kiong (李泽恭) who not only invited them to spend a three-day holiday at his villa in Tretes, a mountain resort nearby, but also offered his car with a driver to take them to Banyuwangi later.

From Banyuwangi, the eastern tip of Java island, they crossed the 3km Bali Strait in 2.5 hours by a small boat called jukung to reach Gilimanuk on the west coast of Bali. Liu Kang described the boat trip on the sometimes choppy water as “a hair-raising episode”.

For those of us used to flying direct from Singapore to Bali in under three hours, it must be hard to imagine what an arduous journey the group chose to take from Singapore to Bali back then. But of course, they got to cover more places and enjoy more sights travelling overland.

Photograph showing Cheong Soo Pieng sketching in a life drawing session as captured by Liu Kang. (Picture from the book Bali 1952: Through the Lens of Liu Kang )

As evident in the images all of them must have found their travels completely worthwhile and richly rewarding, more so in terms of their visit culminating in a groundbreaking exhibition in the following year causing quite a stir.

While the book offers invaluable fresh insights into a most important chapter in our art history, it also leads one to wonder what Liu’s fellow travellers and other artists they met could have added further to the story from their respective records.

Given the legendary friendship between them, wouldn’t Liu Kang have been much taken with Liu Haisu’s direct and fresh Indonesian experiences?

On the eve of their boat trip to Bali from Banyuwangi on 25th June, Liu Kang felt emotional as he looked across the strait. “The paradise I have been dreaming about over a decade was just before me…” he wrote in his diary expressing how much he had longed to see the island.

During the decade before 1952, Liu Kang had been corresponding with Liu Haisu (1896-1994), the renowned artist who taught Liu in Shanghai in the 1920s; both became fast friends when they studied in Paris later. Liu Haisu visited various places in Indonesia to raise funds for China’s war efforts against the Japanese in 1940. Later in the year he came to Singapore where he showed his paintings done on Java and Bali in a fund-raising exhibition in 1941.

Missing element: Inputs of Liu Haisu

Given the legendary friendship between them, wouldn’t Liu Kang have been much taken with Liu Haisu’s direct and fresh Indonesian experiences? However one hardly finds any references to this in their correspondence or any of the records mentioned in the book.

The author describes the appearance of Paris-trained Chinese artist Zhou Bichu (周碧初 1903-1995) in several photographs taken in Bali as mysterious because she has found no mention of him by Liu Kang nor Chen Chong Swee in their writings. Zhou lived in Indonesia for a decade from 1949 and held a major solo show in Jakarta and then Singapore in 1959 before returning to China.

Chen actually wrote a brief article in Sin Chew Jit Poh dated 8 June 1953 recalling how the group met Zhou in Ubud entirely by chance. He felt so excited running into Zhou this way because he had been wanting to meet Zhou since his student’s days in Shanghai 20 years ago. Chen was disappointed that they were not able to spend more time together as their stay in Bali was already coming to an end. It was perhaps unlikely that Zhou could have helped the Singapore artists connect with Le Mayeur and Rudolf Bonnet, both Bali-based European artists, as Gretchen suggests.

Zhou was also reported to have visited Singapore in 1953 at the same time as Georgette Chen and both were warmly welcomed by the Society of Chinese Artists and the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts at a reception at the Botanic Gardens where Liu Kang spoke inviting them to stay in Singapore “to join us in our work and strengthen our ranks”.

The book reveals for the first time that there were actually five rather than four for Bali as we have always known.

Another China artist Luo Ming (罗铭 1912-1998), Liu’s fellow alumnus in Shanghai, who had been sketching and travelling in Southeast Asia since the 1940s, decided to join the group all the way to Bali after a chance meeting in Jakarta. He became widely known for his work on Southeast Asia after returning to China. In 1989 when Luo was in Singapore for a one-man show, his part in the Bali trip did not get any mention at all in media reports. Instead a Lianhe Zaobao article focused on his reunion with art critic Marco Hsu at the exhibition.

Luo’s significant presence in the journey as the fifth participant has come to light now only because he appears frequently in the photographs and narratives in the book.

And then there were five

The book reveals for the first time that there were actually five rather than four for Bali as we have always known.

Seen in the photographs carrying a camera like all the rest except Chen Wen Hsi, Luo should have, one would expect, much to add to the Bali 1952 story with his full participation in the trip. Strangely, based on records available he appears to have hardly ever mentioned this iconic journey for the rest of his life.

Interesting questions such as these from the book should encourage further research on how the Southeast Asian experience of Chinese artists like Liu Haisu, Luo Ming and others could shed light on the development of Nanyang art in Singapore.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)