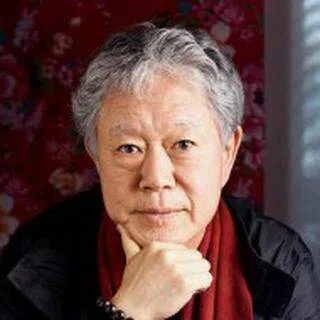

A Taiwanese boy named Thomas and the faith he made his own

Taiwanese art historian Chiang Hsun reflects on his spiritual journey, from youthful devotion to quiet estrangement, contemplating the place of Catholic faith in modern life in the wake of Pope Francis’s passing.

I mourned his death quietly in my heart. It brought back memories of my youth — how I once drew close to the Gospels, was baptised, became a devout believer, and later drifted away from the Church.

Because of him, I began to re-examine the faith I once held in my youth. If I could confess to him now, I would tell him why I left the Church. I imagine he would forgive the impulsiveness of my younger self.

He really was a Sagittarius — he grew up in a poor family, and had even worked as a bouncer at a nightclub. I guess he must have witnessed the hardships of those living on the margins of society.

Having seen poverty, crime and hatred, he could walk with zeal into places steeped in sin and hostility, fall to his knees, and — in the most humble manner — kiss the feet of sinners and embrace his foes.

If Christ is the Son of God, and if Christ came to earth to redeem humankind with His own blood, can the Christian faith still be understood and carried forward, bringing peace to a world riven by conflict, hatred and opposition today?

The roots of my faith

In my youth during the 1960s, I attended Bible class at Penglai Cathedral (蓬莱堂) on Minsheng West Road in Taipei.

Penglai Cathedral was led by Father Ji Chaofang, who had a strong Henan accent. He travelled from Hong Kong and Macau to Taipei in 1953, preaching to the families of retreating soldiers in the Dalongdong area. He also tended to visually and hearing-impaired students in schools for the blind and deaf, gathering many faithful followers in the process.

Father Ji’s accent was difficult to understand. When he was teaching about the Old Testament, there were many names that I only grasped after hearing them countless times — for instance, it took me a while to understand that one rather confusing name he kept mentioning was actually “Abraham”.

In 1960, a new Father Sun arrived at Penglai Cathedral, having just returned from his studies in Rome. He was eloquent and interpreted the Gospels in a lively and open-minded manner. Many young students from the Dadaocheng and Dalongdong areas chose to attend his Bible study classes.

At 14, I attended Father Sun’s Bible class for one and a half years. Everything I studied from the Old Testament to the New Testament left an indelible mark on my life.

How Scripture has shaped classical European art

The Old and New Testaments are the bedrock of classical European culture, much like the foundation of a building. When keeping Scripture in mind, it becomes much easier to understand and appreciate the stories behind countless pieces of European art in museums like the Louvre.

It is not only Michelangelo who depicted the Book of Genesis from the Old Testament on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and The Last Judgement of the Book of Revelation on the altar wall; Western art and literature revolve around biblical narratives, continuously exploring questions of faith.

Even in the 20th century, artists like Salvador Dali were still interpreting the theme of Christ’s crucifixion. French author André Gide also repeatedly examined the spirit of the Gospels in his works — his Les Nourritures terrestres and Les Nouvelles Nourritures possess a beauty and elegance reminiscent of a modern Song of Songs. Meanwhile, his novels reimagine the parable of the Prodigal Son, lending renewed meaning to the themes of rebellion and wandering within the ancient Gospel context.

“When I return in rags, will I also be embraced by my father?”

The power of forgiveness

In Chapter 15 of the Gospel of Luke, the prodigal son squandered everything his father had given him, but ultimately came to his senses and returned home. His father killed a cow and held a feast to celebrate his return, but this angered the older son, who felt that he had never received such love, despite his unwavering devotion and obedience.

“He was lost, and is therefore extraordinarily precious,” Father Sun explained with great depth. I think that I must have also had a “prodigal son” living inside me when I was 15 — one that wanted to run away from home, rebel against my family, and escape from secular rules.

“When I return in rags, will I also be embraced by my father?”

On Sunday, in a small and enclosed confessional booth, I was on my knees, consulting Father Sun through a little window. I knew he was Father Sun, but he said, “When you confess, you’re speaking with God.” He then asked me to recite the Lord’s Prayer three times, which I suppose was intended as a form of reflection.

When Pope Francis passed away, I suddenly recited the Lord’s Prayer once. I have not recited it for over half a century.

I was shocked that I could still remember the line that had touched me the most back then: “And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” It was the boundless, selfless love in the Gospels that led me to believe in Christ, to believe in the existence of God.

“You don’t know the meaning of home if you don’t leave,” the prodigal told his older brother.

Discerning the true meaning of Scripture

Once at the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, I saw a series of monumental Return of the Prodigal Son paintings by the 17th-century Dutch artist Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn. The father embraces his wayward child with warmth; the prodigal kneels before him in tattered clothes, and the father does not utter a single word of reproach.

When I saw the series, I had already left the Church like a self-exiled prodigal, and I did not pray for an embrace upon returning home.

In Gide’s version of the Prodigal Son parable, the ending is reworked — the prodigal son urges his ever dutiful, obedient and faultless brother to leave home. “You don’t know the meaning of home if you don’t leave,” the prodigal told his older brother. In rewriting the parable in this manner, Gide imbued it with a new, modern meaning.

Much of what seems like apostatic literature and art, in fact, is testament to the enduring value of the classics. Whether by adhering to canon interpretations or rebelling against them, faith is still strengthened, albeit in different ways.

This begs the question: what is the Gospel? Is it the word-for-word reading by the priest from the altar? Or is it the product of an intimate relationship with God, which — much like Saint Francis — results in a personal rebuilding of the meaning of faith?

From material wealth to spiritual wealth

I have been to Assisi — Saint Francis’ hometown in Umbria, Italy — several times.

In the 12th century, some priests within the Christian Church merely regurgitated Scripture from their lofty altars in a mechanical manner. The son of a wealthy merchant in Assisi, Francis ate, drank and enjoyed life with young men and women of his age. They likely paid little attention to the endless, repetitive droning from the altar.

Francis later enlisted in the army and served in the war, where he witnessed men slaughtering men and prisoners tortured, locked in dungeons, and suffering from cold and hunger.

When he returned to Assisi, everyone said, “Francis became a different person.” His father urged him to learn to manage the family business, but he was distracted, wandering alone in the hills and wilderness, speaking with birds in the sky and murmuring to the lilies of the field.

On cold winter nights, he welcomed poor and sick itinerant monks, letting them sit by the fire and offering them food and clothing. The next morning, the monks departed and did not carry a piece of clothing with them, returning them to Francis. They thanked him and blessed him, saying, “May your soul prosper.”

How can someone utterly destitute, with nothing at all, bless another by wishing them a richness of the soul? What was the difference between spiritual wealth and material wealth?

Francis was puzzled. How can someone utterly destitute, with nothing at all, bless another by wishing them a richness of the soul? What was the difference between spiritual wealth and material wealth?

Francis stripped himself naked on the streets of Assisi and returned all his clothing to his father. He said, “What material things of yours I had, I now return; my body must go to glorify God.”

One by one, the friends who had joined him in youthful revelry followed him into the mountains, living on wild fruit and drinking from mountain springs. In the forests and caves of the hills dwelt the youths of Assisi. Many of them came from wealthy families, raised in comfort and privilege, yet they gathered around Francis and began to live a life of simplicity and austerity.

When the hippie dream meets Saint Francis’s legacy

My time in Europe coincided with the hippie movement. Many young people left their affluent homes to live simply. They deliberately refused to pay taxes to the government, with some growing their own vegetables and grains in the wild, and many others choosing partners of a different ethnicity.

They yearned for a future in which humanity would no longer be manipulated by capitalism and consumerism, a future where oppressive government surveillance will be no more, and a future where the Berlin Wall would fall, and a future without war, where people could live in peace and harmony.

In their search for utopia, they wandered across different cities and countries. They began to speak about Saint Francis of Assisi once again, retelling the story of the prodigal who had exiled himself from his rich merchant family.

Someone even wrote a biographical novel Brother Sun, Sister Moon, which was also adapted into a film. I then realised that there is also a “Saint Francis of Assisi Church” in Taiwan. I vaguely recall seeing their friars in their simple robes, with a hemp rope tied around the waist.

More than just a name

So why didn’t I choose “Francis” as my baptismal name?

Before a Catholic is baptised, s/he chooses the name of a saint, such as John, Peter, Mary, Agnes, Magdalene, Gabriel or Matthew. Father Sun explained to me the significance of each name.

It felt somewhat like redefining the meaning of one’s own life. My Chinese name was chosen by my father, but in the Catholic faith, baptism seemed to offer a chance to give myself an entirely new identity. Back then, I had been deciding between two names: Peter and Thomas.

I considered Peter because I liked that he had denied Christ three times. The story is written in Matthew 26, John 18 and Luke 22. In the story, Jesus led his disciples to the Garden of Gethsemane, but they soon fell asleep. Jesus knew he would soon be arrested, and told Peter that after His arrest, he would deny Him three times before the rooster crowed. Peter declared that he would remain loyal and guard the Lord, insisting that he would never betray Him, even if it meant that he would be killed.

As Jesus had foretold, He was subsequently arrested, and Roman soldiers began hunting down His followers. I guess all political persecutions are the same: followers panic and flee as quickly as they can. As Peter fled, someone accused him of associating with Jesus, but he denied it three times. After the third denial, he heard the rooster crow and remembered Jesus’s words the night before.

Peter’s story appalled me. Faith can actually be so fragile — vowing loyalty just moments before, but doing the exact opposite just the minute after. I thought about using Peter as my baptism name, to remind myself to constantly face my own weaknesses in matters of faith.

Peter later became the first Pope, and Jesus gave him the keys of the kingdom of heaven. But perhaps I disliked a Church that held the keys to heaven. There was, after all, a time when the Church wielded them to oppress people, by selling indulgences and engaging in greedy and corrupt behaviour.

The true altar and sanctuary are found in every individual that welcomes faith.

The importance of doubt to faith

This is why I did not choose Peter. Father Sun smiled, and asked me to pick “Thomas”. Thomas was notorious for being a doubter — “he did not believe that Jesus had risen, and needed to see it with his own eyes and place his hand into Jesus’s side before he did.”

What becomes of faith if there is no doubt, no evidence and no lived practice?

I therefore picked the name “Thomas”. At my baptism, I reminded myself to always remember God’s love and mercy. I warned myself that if faith loses its capacity for questioning — if it lacks even the courage to betray — then faith becomes nothing more than a disguise for servility, not true belief.

With my baptism name “Thomas”, I became a devout Catholic. Every week, I attended Sunday Mass, went to confession, and sincerely examined and repented of the wrongs I had done. Kneeling at the altar to receive the Eucharist, I felt the small wafer — representing God’s body — dissolve in my mouth. It felt as though my body itself became a dwelling place for God.

Finding God through quiet faith and in everyday miracles

I believe that God was never found on the altar, nor in grand churches. The true altar and sanctuary are found in every individual that welcomes faith. As Rabindranath Tagore wrote in a poem: He is there where the tiller is tilling the hard ground and where the path-maker is breaking stones.

Thomas always doubted the collective emotions stirred up among the masses, and watched the miracles on the altar calmly. After all, what is a “miracle”? Making the blind see? Letting the lame walk? The dead rising from their graves?

Though more and more followers gathered around Saint Francis, he continued to live a simple, ordinary life, speaking in beautiful, everyday language to the clouds in the sky, to spring water thawed by the warmth of the season.

Some pretentious followers demanded miracles from Francis. “How can you become divine if you cannot perform miracles?” they questioned. Francis led them to look at the new leaves budding on the treetops in spring: “Look — this is the miracle…”

Francis was close to nature; he believed that nature was filled with miracles. Yet these followers still pressed him for miracles — more dramatic miracles, more crowd-pleasing wonders.

The wounds we cannot bear

One stormy night, Francis prayed alone on the mountaintop. Here, there is a gap in his story. It is said that after the storm, people found Francis collapsed on the mountaintop, bearing five wounds on his body similar to those Jesus suffered during the crucifixion — two nail wounds on his hands, two on his feet, and a spear wound on his side, which was the very wound that Thomas had touched. These stigmata — the specific wound pattern — made Francis a saint.

But can we bear the wounds that Christ once bore? In Assisi, I saw a robe Francis had left behind, which had been patched and mended over and over. It reminded me of Master Hong Yi’s robe that I saw in Hangzhou’s Hupao Temple — it had also been patched over numerous times.

Perhaps they had been reborn into this world in another life, still carrying their ancient wounds and clothed in rags, to see if creation was at peace.

Yes, Francis became “Saint” Francis. And a thousand years later, a Pope who came from a poor Argentine family would choose “Francis” as his papal name — the first Pope ever to do so.

He certainly lived up to his name. Pope Francis did not place himself above others. He walked into prisons and kissed the feet of inmates. He approached the Eastern Orthodox Church, divided from Rome for a thousand years, and embraced them. He apologised to the Arab world for the Crusades.

The priest was a little startled. He hesitated for a moment: since the Eucharist is sacred, could it be given to a homeless man in rags?

Today, is there any political leader who can embrace an enemy? If one cannot embrace an enemy, how can one understand the Gospel’s teaching: Love your enemies?

The return of the prodigal son

Why did I leave the Church, even after choosing the name “Thomas” for myself? I believe it was on Christmas Day when I was 17. I was at Penglai Cathedral attending Midnight Mass. I went to confession, read the Scriptures, and cleansed my body, ready to receive the Eucharist.

Kneeling conspicuously before the altar, among a row of worshippers, was a homeless man in tattered clothes. Everyone else had come dressed in their finest clothes for Midnight Mass (the Church sometimes inadvertently reinforces class), and the man’s rags stood out sharply, startling the well-dressed worshippers.

Thomas watched quietly as the priest held the silver chalice with the Eucharist, distributing it to each worshipper. The homeless man was in front of me, kneeling down with mouth wide open — perhaps more eager than anyone else to receive the blessing. His mouth opened unusually wide, his cheeks hollowed, reminding me of the suffering face of Christ on the cross.

The priest was a little startled. He hesitated for a moment: since the Eucharist is sacred, could it be given to a homeless man in rags? In those few seconds — perhaps it was Thomas speaking in me, or perhaps it was the universal wavering that grips anyone standing at the threshold of faith — the priest faltered.

In the end, the priest refused to give the blessing. The homeless man was disappointed and distressed, and the young Thomas stood up and left the Church. I didn’t know why, but I very much wanted to confess to Saint Francis and to embrace my enemies under his spirit of compassion.

Why did I not know then that I could have simply chosen Francis — his love, his gentleness, his compassion — as my new self?

This article was first published in Chinese on United Daily News as “射手教宗方濟各”.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)