China’s factory exodus is turning Vietnam into the world’s assembler

What started as a trickle during the early days of the US-China trade war has become a torrent. To retain access to US markets, companies that have long powered China’s export engine are setting up shop in Vietnam, drawn not only by low labour costs but gains in tariff relief and improved regional access.

(By Caixin journalists Zhang Erchi from Vietnam and Han Wei in Beijing)

A 90-minute drive north of Hanoi, a red banner with gold Chinese characters wishing prosperity flutters over the gate of Mingjie Co. Ltd.’s newly completed factory. Inside, brand-new injection molding machines stand idle, awaiting activation. Outside, farmers in conical hats work rice paddies.

Once a quiet patchwork of farming villages, Bac Ninh is emerging as the industrial engine of northern Vietnam. The transformation reflects a broader trend as Chinese manufacturers steadily move operations southward in response to US tariffs and an overhaul of global supply chains.

What started as a trickle during the early days of the US-China trade war has become a torrent. To retain access to US markets, companies that have long powered China’s export engine are setting up shop in Vietnam, drawn not only by low labour costs but gains in tariff relief and improved regional access.

Dongguan-based Mingjie, a manufacturer of plastic casings for electronics, epitomises this trend. For more than 20 years, it exported around the world from China. But by the end of 2023, growing client pressure made a new strategy unavoidable.

“When the trade tensions began in 2018, one client suggested we look into Vietnam,” said Li Fangting, who oversees the company’s foreign trade operations. “After the pandemic, those suggestions turned into demands. Some clients said we wouldn’t be considered for new orders unless we had a presence in Vietnam.”

Mingjie followed its largest client to Bac Ninh, where it now manufactures parts for export to Europe and the United States.

Northern Vietnam is undergoing a rapid transformation as industrial parks proliferate and cities like Bac Ninh begin to resemble the factory towns that sprang up in Guangdong province two decades ago.

Yet, this relocation strategy is being tested by rapidly escalating costs. Fierce competition for premier industrial sites and skilled labour is squeezing margins, forcing many firms into a precarious position: producing goods that cost more than their Chinese equivalents, while betting their survival on a tariff gap that could vanish with a single political decision.

In April, US President Donald Trump imposed a 46% reciprocal tariff on Vietnamese exports. A bilateral deal in August reduced that to 20%, still higher than the 19% average for other Southeast Asian peers.

The new world assembler

Northern Vietnam is undergoing a rapid transformation as industrial parks proliferate and cities like Bac Ninh begin to resemble the factory towns that sprang up in Guangdong province two decades ago. The region now hosts a mix of global manufacturers — from South Korea’s Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. and Japan’s Canon Inc. to a growing roster of Chinese firms, including Apple suppliers like Goertek Inc.

“Over the past few years, we’ve seen a surge in supply chain companies, logistics providers, and packaging firms entering Vietnam, following in the footsteps of their major clients,” said Anchalee Prasertchand, an executive at Thailand’s WHA Group, an industrial park developer. As small and midsize firms like Mingjie arrive, Vietnam is deepening its role as the world’s assembler.

Vietnam’s industrial base has grown in waves. The first influx came in the late 1980s, when Asian neighbours sought to escape rising production costs. The most recent surge is a direct consequence of the US-China trade war.

Hang Vay Chi, a Vietnamese-Chinese businessman who established the country’s first private industrial park outside Ho Chi Minh City in 1987, recalled that most early tenants were small and midsize Taiwanese firms in labour-intensive sectors. By 2007, when his second park opened, nearly 70% of occupants were from the Chinese mainland, many from Dongguan and Shenzhen.

The momentum intensified after 2018, when Washington slapped tariffs of 10% to 25% on a wide range of Chinese goods. Niu Qiang, general manager of KCN Investment Consulting (Vietnam) Co. Ltd., said inquiries from Chinese firms rose from one a week in 2016 to six or seven a day by 2018.

Many gravitated to northern Vietnam, where electronics manufacturing had already taken root. Samsung set up phone production in Bac Ninh in 2008 and steadily expanded, investing more than US$23 billion to become Vietnam’s largest foreign investor. Since 2017, Apple suppliers such as Foxconn, Goertek, Luxshare Precision and Lens Technology have followed, deepening the region’s role in global supply chains.

... between 2018 and 2022, the share of US imports indirectly sourced from China via Vietnam jumped 21%, notably in textiles, footwear, and electronics.

Vietnam’s proximity to southern China adds to its appeal. Components from the Pearl River Delta can reach Bac Ninh within days by road or about a week by sea, Mingjie’s Li said.

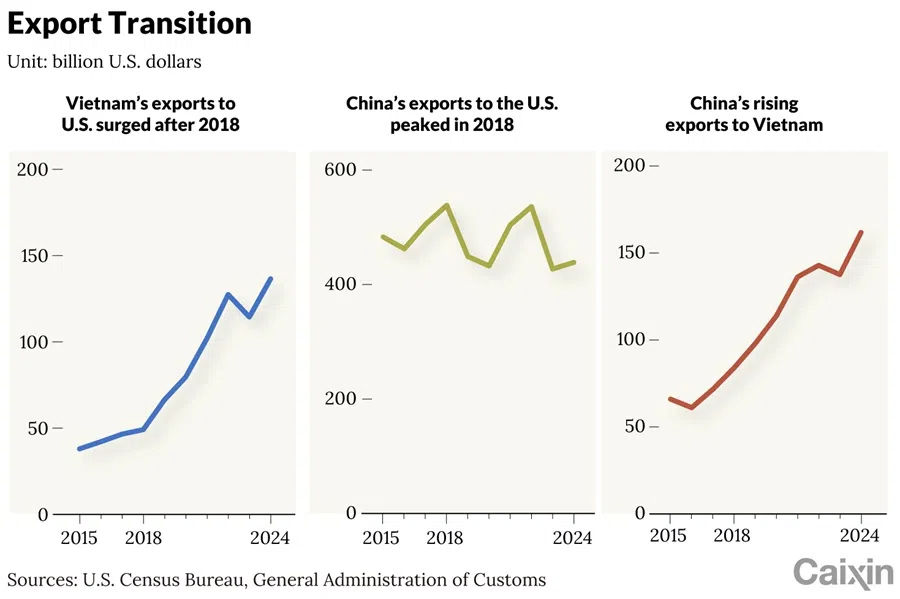

This migration is reshaping global trade flows. In 2019, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) overtook the US to become China’s second-largest trading partner, then surpassed the European Union in 2020 to take the top spot. Bilateral trade reached US$982.3 billion in 2024, with Chinese exports climbing 12% to US$586.5 billion.

Vietnam has been China’s largest ASEAN trading partner since 2016. In 2024, it imported US$144.3 billion in goods from China, leading to a trade deficit of US$83.7 billion. Conversely, the US remained Vietnam’s largest export market, buying US$119.6 billion in goods and generating a US$104.6 billion surplus.

A study by the Chinese University of Hong Kong found that between 2018 and 2022, the share of US imports indirectly sourced from China via Vietnam jumped 21%, notably in textiles, footwear, and electronics. Over the same period, China’s direct share of US imports fell from 21.6% in 2017 to 13.4% in 2024, while Vietnam’s share more than doubled, rising from 2% to 4.2%.

The new cost equation

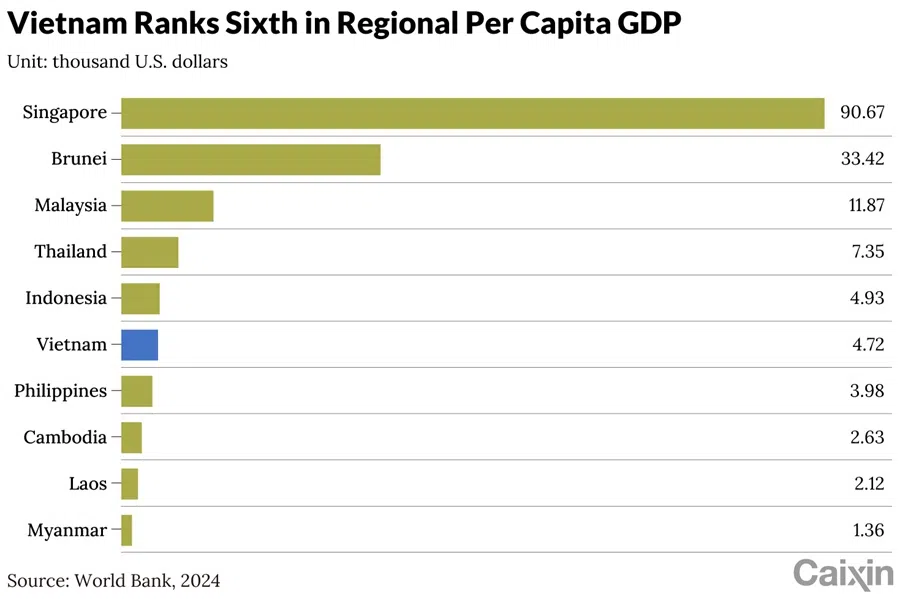

For years, Vietnam’s growth was powered by its abundant, low-cost labour. That demographic dividend is now giving way to a different — and less predictable — draw for foreign investors: the tariff dividend.

The influx of businesses has sharply driven up costs. Dongguan-based Hechang Threads Dyeing Co. Ltd., which built a plant in Ho Chi Minh City in 2002 to supply shoemakers such as Nike and Adidas, once paid local workers about 200 RMB a month compared with 1,500 RMB in Dongguan. Today, average factory wages have climbed to 2,500 to 3,000 RMB, narrowing the gap with China’s interior provinces.

Land is even more expensive. In Bac Ninh, industrial plots fetch nearly 1 million RMB per mu (US$200,000 per acre), two to three times higher than in parts of China. One Chinese furniture maker warned that rents can swallow a third of expenses, leaving firms exposed to downturns.

... Vietnam’s incomplete supply chain remains a bigger challenge as many parts must still be imported from China...

Still, Vietnam continues to enjoy a demographic dividend with roughly 1 million babies born each year, according to Ou Kui, senior adviser to the Vietnam Textile and Apparel Association and chairman of H&K Investment Co. A baby boom in 2003 and 2004 pushed annual births to 1.5 million. That cohort is now entering the workforce, providing fresh labour for factories. By contrast, China’s manufacturing workforce is aging and their children are less inclined to take factory jobs — creating a looming generational gap.

Despite rising costs, favourable US tariffs still make Vietnam attractive. Executives say higher costs for imported Chinese components, coupled with rising wages and land prices, make Vietnamese-made goods about 15% more expensive than those from China. Even so, US tariffs averaging 57.6% on Chinese goods versus 20% on Vietnamese goods leave a 37.6-point gap that keeps manufacturers moving across the border.

The supply chain gaps

For foreign businesses, Vietnam’s incomplete supply chain remains a bigger challenge as many parts must still be imported from China, Chinese executives told Caixin.

In electronics, local sourcing is improving as giants like Samsung and Foxconn expand. Li of Mingjie said about 70% of the company’s raw materials can now be procured locally, though complex precision parts and molds still need to be imported.

In furniture, decades of development have created a relatively self-sufficient ecosystem. A Chinese furniture maker noted that 90% of inputs — such as hardware, paint and packaging — are available domestically. But production capacity for some wood panels is still lacking, and reliance on imported iron reflects Vietnam’s limited steelmaking base.

“In fact, the global centre of furniture production shifted from Dongguan to Binh Duong by 2018,” the factory owner said. “This industry won’t be going back to China.”

By contrast, textiles remain heavily dependent on Chinese inputs. Tian of Hechang said 80% of raw yarn still comes from China. Weak refining capacity means Vietnam cannot meet demand for petrochemical-derived fibers, while stringent environmental reviews have slowed investment in dyeing and finishing. As a result, importing from China by sea — a week-long trip — remains the norm.

Ou argued that Vietnam’s government lacks the fiscal resources to subsidise firms or discount land to encourage full supply chain relocation, making it harder to attract investment in the same way China once did.

The US role is increasingly important. Under a trade agreement signed in July, Washington will impose a 40% tariff on goods transshipped through Vietnam from third countries — double the rate on Vietnamese-made goods. But with Vietnam still so dependent on Chinese components, what qualifies as “transshipment” remains unclear.

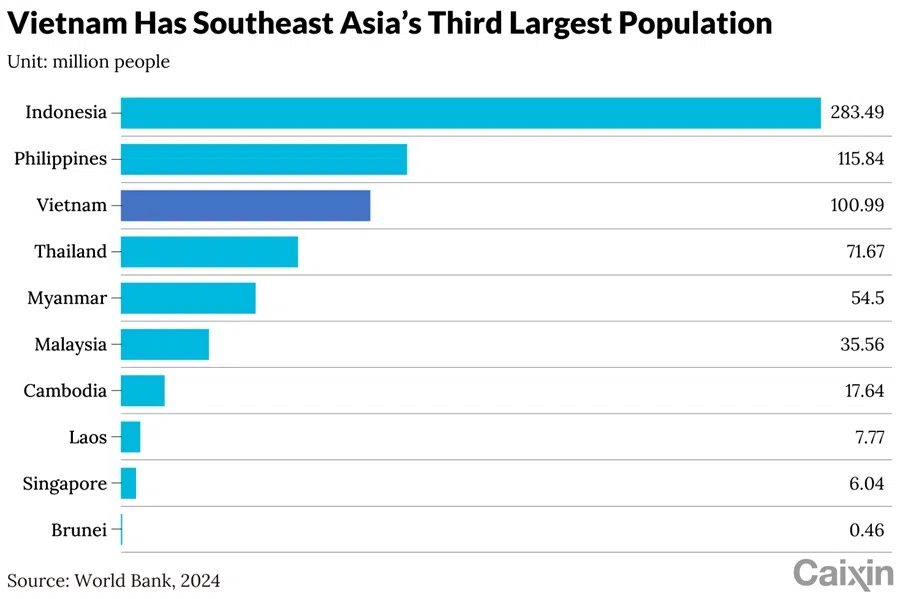

... with its 100 million people — ranking third among ASEAN countries behind Indonesia and the Philippines — and an economy growing at more than 7% a year, Vietnam is set to become an attractive consumer market in its own right...

For now, Chinese firms are cautious. KCN’s Niu said rising land costs, labour shortages and incomplete supply chains are prompting hesitation. Still, Vietnam’s free trade deals with the EU and ASEAN countries promise eventual tariff-free exports, giving the country staying power as China’s offshore export base.

“Trade wars may be the spark, but going overseas is really about tapping global markets — not just the US, but also Europe and Southeast Asia,” Niu said. “For Chinese companies, this is the true start of globalisation.”

Southeast Asia’s beachhead

For most Chinese firms, Vietnam is still primarily a manufacturing base, with finished goods destined for developed markets. But with its 100 million people — ranking third among ASEAN countries behind Indonesia and the Philippines — and an economy growing at more than 7% a year, Vietnam is set to become an attractive consumer market in its own right and a strategic “bridgehead” for the broader Southeast Asian market.

That shift is already underway. Zheng Dong, who founded Wowbuy which helps Chinese brands enter Vietnam, said Southeast Asia’s diverse development stages and cultural backgrounds make it a training ground for global expansion. Lessons learned here, he argued, can be applied worldwide.

The key, Zheng emphasised, is deep localisation, not just low prices, to win over a region far more complex than many Chinese firms expect.

Shineray Motors, part of Chongqing-based Shineray Group, illustrates both the challenge and opportunity. The company entered Vietnam in 2018 by acquiring a local minivan maker. It now employs more than 200 workers and can produce 25,000 vehicles a year.

To attract local customers, Shineray re-engineered its vehicles for Vietnam. It shortened truck wheelbases to better navigate the country’s notoriously narrow alleys and designed seven types of truck beds to cope with the monsoon climate, including features to ventilate produce, according to general manager Wang Lu.

The strategy paid off. In the first half of this year, Shineray’s mini-commercial vehicles captured 30% of the market, surpassing Japan’s Suzuki, the long-time leader.

Shineray is now preparing for Vietnam’s planned restrictions on gasoline-powered cars in major cities by 2026. “Now is a good time to lay the groundwork for the passenger car and new energy vehicle market,” said Wang, who sees the country as a launchpad for the rest of ASEAN.

Shineray is not alone. China’s automotive giants are following suit. In September, Geely Auto announced a US$168 million joint venture to assemble cars in Vietnam. That same month, Great Wall Motor signed a deal to begin local production by the end of 2025, cementing Vietnam’s role as both a critical manufacturing hub and a fiercely contested consumer battleground.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “Cover Story: China’s Factory Exodus Is Turning Vietnam Into the World’s Assembler”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.