How gutter oil became a prized fuel for international airlines

Once scorned as a public health hazard, China’s notorious “gutter oil” or used cooking oil (UCO) has been recast as one of the world’s most sought‑after feedstocks for sustainable aviation fuel — fetching prices higher than conventional jet fuel as airlines rush to cut carbon and meet global mandates.

(By Caixin journalists Zou Xiaotong, Fan Ruohong and Han Wei)

Once reviled as a public health menace in China, “gutter oil” is now a prized commodity.

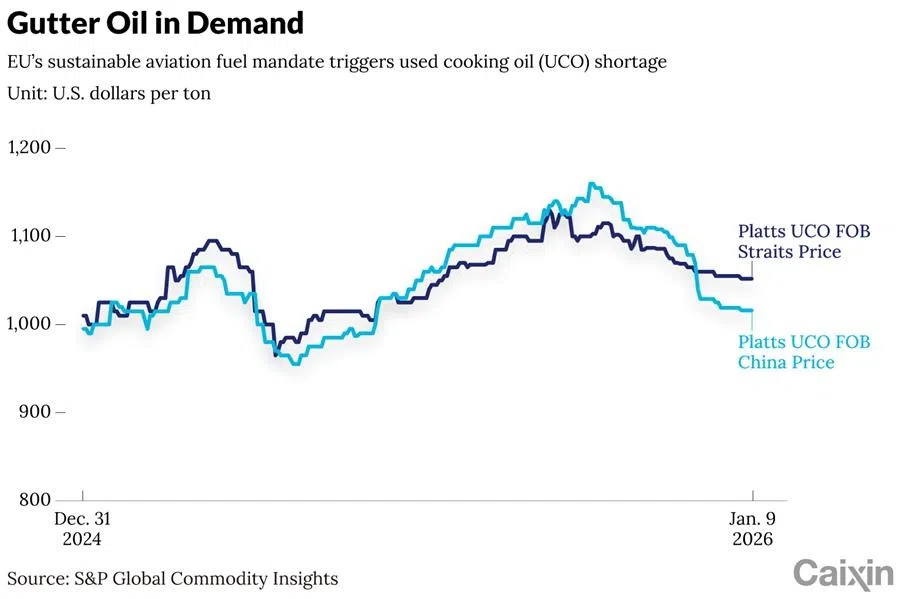

Used cooking oil (UCO), to give it its more formal name, has become one of the world’s most sought-after feedstocks for sustainable aviation fuel. Prices have soared as airlines scramble to cut carbon emissions and comply with tightening international mandates. In 2025, a ton of UCO sold for hundreds of dollars more than conventional jet fuel.

“Can you imagine gutter oil being more expensive than olive oil?” said James Tam, co-chairman of EcoCeres, the world’s second-largest sustainable fuel producer, and a partner at Bain Capital Asia.

China is at the centre of this global shift. Once notorious for underground networks that reprocessed gutter oil for resale to restaurants, the country now supplies more than 40% of the world’s traded UCO. It is now increasing production of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), scrapping export tax rebates to retain raw materials and issuing quotas to control how much goes abroad. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), China could account for 13% of the world’s SAF capacity by 2030.

More than a decade ago, UCO used to be extracted from sewers and drains and illegally recycled into the food supply. Today, refined through advanced processes, it fuels aircraft across continents. The fuel made from gutter oil can now be blended seamlessly with conventional jet fuel and reduces lifecycle carbon emissions by up to 80%.

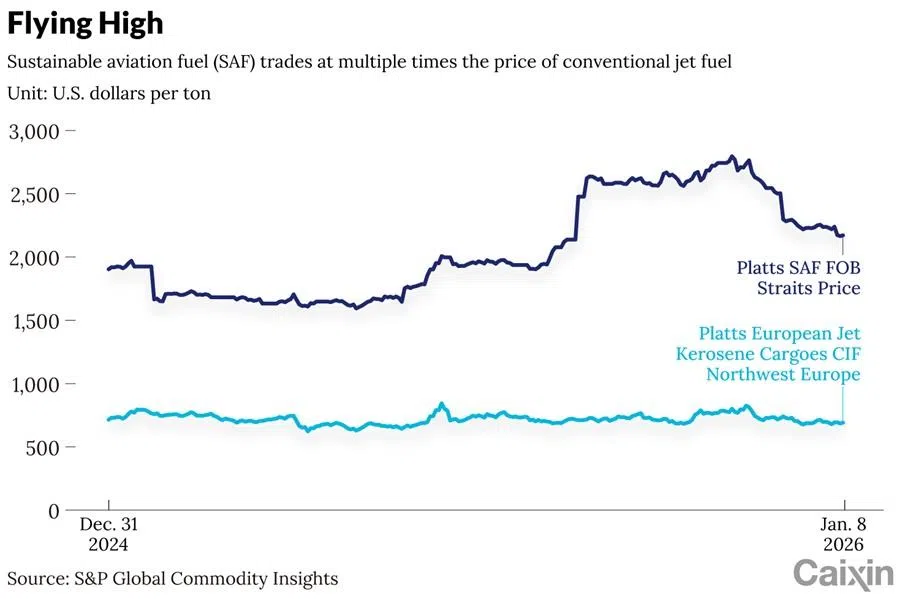

With 2025 marking the start of mandatory SAF blending in several markets, UCO prices have rocketed. S&P Global Energy data show that in China its price had reached US$1,160 per ton by 2025, a 17.2% increase from the start of the year. Airline fuel refined from this oil fetched up to US$2,642 per ton — nearly four times the price of fossil-based jet fuel.

As rules become stricter, costs are mounting and profitability is being squeezed. The move to greener fuels is no longer just a matter of innovation — it is becoming a test of economic viability.

The soaring prices underscore a supply-demand imbalance. A report by Peking University’s National School of Development noted that SAF remains constrained by feedstock scarcity, immature technology and fragmented supply chains. Compared with traditional fuels, it is less efficient and significantly more expensive to produce.

For airlines, this is more than a climate challenge — it is a financial one. As rules become stricter, costs are mounting and profitability is being squeezed. The move to greener fuels is no longer just a matter of innovation — it is becoming a test of economic viability.

The real test comes in 2027, when the International Civil Aviation Organization begins to enforce its global carbon offsetting and reduction scheme...

The mandate clock is ticking

Commercial aviation, which is responsible for an estimated 2% to 3% of global carbon emissions, is widely acknowledged as one of the hardest sectors to decarbonise. Unless kept in check, those emissions are expected to more than double by 2050 from 2019 levels.

To avoid that happening, regulators are moving swiftly. The European Union has taken the lead by requiring 2% of all jet fuel supplied at its airports to be SAF by 2025 as part of its RefuelEU Aviation initiative. That figure is due to rise to 6% by 2030 and 70% by the middle of the century. Britain is implementing a similar framework.

Other governments are falling in line. Singapore intends to impose a 1% SAF blend rule from 2026. Japan, South Korea, and India have also set blending targets. While China and the United States have not imposed consumption mandates, both are investing heavily in SAF production.

The real test comes in 2027, when the International Civil Aviation Organization begins to enforce its global carbon offsetting and reduction scheme, known as Corsia. Airlines that fail to demonstrate sufficient carbon offsets or SAF usage will face penalties.

According to IATA, sustainable aviation fuel will account for about 65% of the industry’s carbon reductions needed to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. That implies a global SAF demand of roughly 358 million tons a year — far in excess of current output.

In 2025, the entire Chinese aviation sector earned only 6.5 billion RMB (US$934 million) in profit — a small rebound after nearly 400 billion RMB in combined losses over the pandemic.

In 2025, SAF production nearly doubled but still only accounted for a small share of total aviation fuel. Airlines paid an estimated US$2.9 billion premium for SAF that year alone, IATA data showed.

The shortfall is especially stark in Europe. Analysts estimate the EU currently needs 1.4 million tons of SAF and this will rise to 3.5 million tons by 2030, and 50 million tons by 2050. Yet current production capacity barely exceeds 1 million tons a year, according to the European Union Aviation Safety Agency — just enough to meet the 2030 target of 6%. Achieving 20% by 2035 would require a massive build-out.

Globally, SAF projects are concentrated in Europe and North America. As of early 2026, at least 559 SAF projects across 63 countries were operational, under construction or planned, according to the International Civil Aviation Organization. Their combined projected capacity exceeds 37 million tons. But industry experts say constrained feedstock and limited policy support will continue to suppress supply and keep prices high.

“Rising compliance costs and the SAF premium are already compressing the industry’s thin profit margins,” Hemant Mistry, IATA’s director of energy transition, told Caixin.

The pressure is already being felt. A source at one of China’s three largest state-owned airlines told Caixin the company had spent heavily on SAF for its Europe-bound flights, despite the absence of domestic mandates. In 2025, the entire Chinese aviation sector earned only 6.5 billion RMB (US$934 million) in profit — a small rebound after nearly 400 billion RMB in combined losses over the pandemic.

“Many countries around the world need gutter oil, so when I travel on business, I try to eat more hotpot.” — Yu Feng, President, Honeywell China

China’s gutter oil rush

As global SAF demand increases, China has become a vital source of feedstock. Its large population and oil-rich cuisine generate substantial volumes of waste oil — though even that supply is insufficient.

“Many countries around the world need gutter oil, so when I travel on business, I try to eat more hotpot,” joked Yu Feng, president of Honeywell China, during a business roundtable in December. In just two years, prices for the waste oil have quadrupled, he added.

Restaurants have begun to see used cooking oil as a reliable revenue stream. It can fetch between 4,000 and 5,000 RMB a ton, according to Ye Bin, chairman of Sichuan Jinshang Environmental Technology Co. Ltd., a waste collection company. “It has become a stable source of income for restaurants,” he said.

Honeywell estimates that China could in theory supply 10 million tons of UCO a year but only about 5 million tons are currently collected. Using its proprietary refining technologies, 10 tons of the oil can be converted into roughly 8 tons of SAF.

Until recently, much of this valuable resource was shipped abroad. Data from Cinda Securities Co. Ltd. showed that more than 50% of China’s collected UCO was exported. But in 2024, China scrapped a 13% export tax rebate on the product, aiming to retain more of it for domestic SAF production.

Policy shifts abroad also played a role. In early 2025, the EU imposed anti-dumping tariffs on Chinese biodiesel — but exempted SAF. That distinction has prompted Chinese firms to concentrate on SAF exports.

According to Soochow Securities Co. Ltd., China’s UCO exports rose from 340,000 tons in 2017 to 2.95 million tons in 2024. During the first 11 months of 2025, however, export volumes fell 11% year-on-year to 2.48 million tons, even as average prices climbed 21%.

China’s SAF pivot

China is moving beyond raw material exports and becoming a major fuel producer. By the end of 2025, five domestic SAF producers had passed airworthiness certification. Together, they produced 1.375 million tons that year — triple the figure from 2024. Construction allowing the production of 4.35 million tons is either under way or being planned.

For now, most of this output is heading abroad. To regulate the trade, Beijing in 2025 imposed an export quota system on qualified producers. The recent creation of a dedicated customs code for SAF further underscores the central government’s intent to monitor and manage this strategic commodity.

A research institute under China Petrochemical Corp (Sinopec) estimated that by 2030, SAF will account for about 3% of China’s total aviation fuel consumption, translating into a demand of 1.2 million to 1.5 million tons a year.

Yet the long-term direction of the industry remains tied to domestic policy signals. “The Chinese SAF market is still waiting for a clearer signal from policy,” said Wang Yangwen, Asia-Pacific price director for S&P Global Commodity Insights. One key unknown is whether China’s 15th Five-Year Plan for the aviation sector will include a national SAF consumption target — a move that would help future capacity decisions.

Meanwhile, the market is awaiting the potential merger of Sinopec, the world’s largest refining company, and China National Aviation Fuel Group, the country’s sole aviation fuel supplier. A vertical consolidation of that scale could dramatically reshape the SAF sector, raising questions about how it might affect private producers, who currently account for roughly 90% of the nation’s SAF capacity.

If China were to mandate a 2% SAF blend, the total added cost for airlines would reach approximately 8 billion RMB (US$1.2 billion).

A costly conundrum

The “green premium” remains a central obstacle as the SAF currently costs two to five times more than conventional jet fuel — a burden cash-strapped airlines are ill-equipped to shoulder without subsidies. “The industry has to make money first before it can develop,” said an executive at a private Chinese airline.

How to manage that cost burden is subject to a growing debate. One proposal from Peking University’s National School of Development suggests passing part of the cost on to consumers. If China were to mandate a 2% SAF blend, the total added cost for airlines would reach approximately 8 billion RMB (US$1.2 billion). Spread across the 730 million passenger trips recorded in 2024, that would mean an 11-RMB (US$1.50) surcharge per ticket.

At the same time, the industry is grappling with the limitations of existing technologies. The most commercially mature production method — hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA) — relies heavily on used cooking oil and other forms of waste fat, both of which face supply constraints.

“HEFA can only meet the first wave of SAF demand,” said EcoCeres’ James Tam.

Thanks to its abundant agricultural waste and its status as the world’s largest installer of wind and solar power, China is uniquely positioned to take the lead in next-generation SAF development.

In response, China is actively exploring alternative production routes, including Alcohol-to-Jet (AtJ), which uses non-edible biomass such as agricultural residues, and Power-to-Liquids (PtL), which harnesses renewable electricity and captured carbon dioxide to synthesise liquid fuels.

Nie Hong, chief expert at Sinopec, has suggested a phased approach: rely primarily on HEFA until around 2035, then move to large-scale deployment of AtJ and other technologies, with PtL becoming a core solution after 2045.

Thanks to its abundant agricultural waste and its status as the world’s largest installer of wind and solar power, China is uniquely positioned to take the lead in next-generation SAF development. Pilot projects are already under way. One involves Sinopec’s Yanshan Petrochemical unit, which plans to produce SAF using a gasification and Fischer-Tropsch synthesis pathway — which converts solid carbonaceous feedstock into high-quality fuel — potentially powered by green hydrogen delivered via a new 1,100-kilometre pipeline stretching from Inner Mongolia.

As the global SAF compliance deadline in 2027 approaches, Beijing faces mounting pressure to find a policy balance — one that advances its ambition to become a clean energy superpower while managing the immense cost of decarbonising flight.

Luo Guoping and Qu Yunxu contributed to the story.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “Cover Story: How Gutter Oil Became a Prized Fuel for International Airlines”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.