China's crackdown on pretty boys and temple temptresses: Why are Chinese women feeling targeted?

The Chinese authorities are not just clamping down on celebrities for their excesses or "unhealthy' fandoms, but setting the ground rules for media portrayals of gender norms of appearance and behaviour. In particular, the "effeminate aesthetics" of male celebrities and female influencers marketing themselves in Chinese temples have come under attack. But why are Chinese women feeling targeted? Are these necessary actions to moderate the internet economy or just signs of an over-the-top paternalistic bent?

Following a crackdown on the entertainment industry, China's male celebrities are looking more masculine these days.

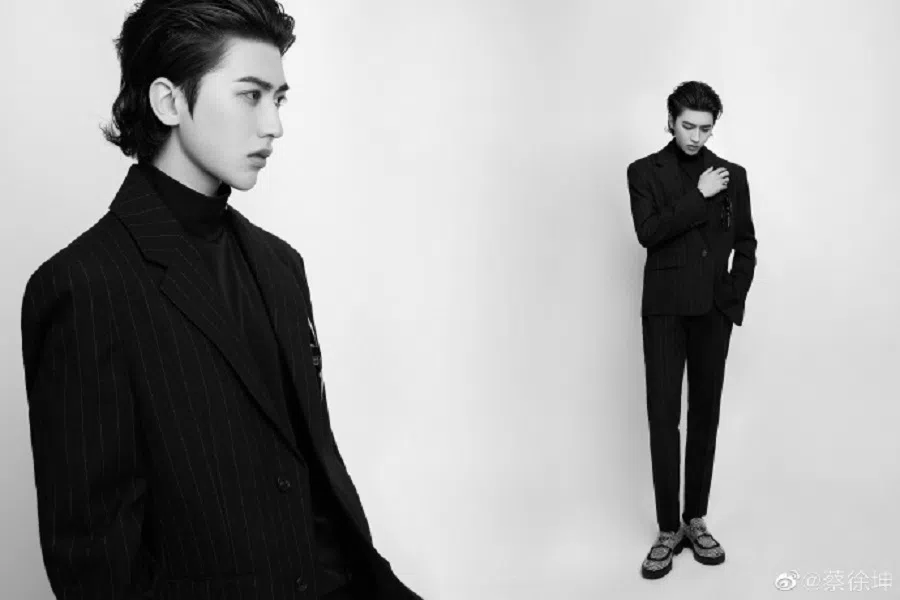

Once known for his Korean pretty boy image, Chinese singer-songwriter Huang Zitao recently posted a photo of himself at the gym with his six packs in clear view. Chinese actor Wang Yibo, who shot to fame after starring in a period drama, has cut his hair short. Chinese singer Cai Xukun, a talent show alum, now has a beard and flexed his muscles for a magazine shoot. It seems that many erstwhile pretty boys are transforming into masculine men to dissociate themselves from the "effeminate" image that Chinese officials have recently banned.

Early this month, the Chinese National Radio and Television Administration unveiled a plan to promote "correct" beauty standards across all platforms to "resolutely put an end to sissy men and other abnormal esthetics". On 18 September, the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Radio and Television released a statement saying that it has tightened the guidelines on drama production in terms of casting, performance style, costume and makeup so as to put an end to "effeminate" aesthetics. Participation in publicity events promoting this aesthetic style is also prohibited.

Making gender-stereotypical judgements of physical appearance

The derogatory term niangpao (娘炮, lit. girlie guns, meaning "effeminate, sissy") is used to describe effeminate men. China Women's News (《中国妇女报》) once banned the use of this term because of its sexist nature. Early in 2018, public opinion had also turned against the rising trend of effeminate celebrities in the entertainment industry.

Back then, a China Central Television programme "First Class of New Semester" (《开学第一课》) targeted at primary and secondary school students had invited several young male pop idols to appear on the show as guests. Some parents complained that the idols did not look masculine enough, and became worried that this would affect their child's perceptions of male/female attractiveness.

State media Xinhua News Agency then published a commentary under the name "Xin Shi Ping" (辛识平, a homophone and acronym for Xinhuashe Shishi Pinglun 新华社时事评论, Xinhua's current affairs commentary section), criticising the trend of effeminacy in the entertainment industry as a perverse culture and cautioning that the negative impact of this culture on the younger generation cannot be underestimated.

However, a WeChat article posted by the commentary section of the People's Daily offered a different view. It said: "To equate manliness with appearance is a simplistic approach." It also rejected the use of derogatory terms like niangpao and bu nan bu nü (不男不女, lit. not male not female; to look neither like a male nor a female).

...the worship of pretty boys is the reason for the chaos and problems in the entertainment industry. - Chinese authorities

Singing the same tune

Compared with the situation three years ago when there were differing views, various state media are now on the same page as the ban on effeminate aesthetics has been made official. On 27 August, Guangming Daily attacked the film and television industry for casting pretty boys as the protagonist, making characters who should be manly and strong waifish and weak instead. The piece further suggested that pretty boys would stoop to hyping up scandals and instigating fan disputes to raise their popularity.

Clearly, officials have lumped the trend of effeminacy with the like economy and a disorderly fandom culture, asserting that the worship of pretty boys is the reason for the chaos and problems in the entertainment industry.

Would the notable late Peking opera singer Mei Lanfang, who was known for his exceptional rendition of female lead roles, or Jia Baoyu, the male protagonist of Dream of the Red Chamber, be labelled as "effeminate" males in today's terms? - Chinese netizens

The strange thing is, official documents did not give a clear definition of effeminate aesthetics. Netizens asked: What would be considered effeminate or sissy then? Would it be wearing earrings and having long hair? Or having delicate features and a mild manner? Would the notable late Peking opera singer Mei Lanfang, who was known for his exceptional rendition of female lead roles, or Jia Baoyu, the male protagonist of Dream of the Red Chamber, be labelled as "effeminate" males in today's terms?

Netizens flagged that a categorical crackdown on a certain type of physique and appearance could result in the ostracisation of men who have a gentle demeanour. They could even become victims of bullying.

From effeminate men to Buddhism influencers

Before the debate on effeminacy has a chance to die down, another group of internet celebrities is coming under attack - the mostly female foyuan (佛媛, Buddhism influencers, referring to internet celebrities who like to take flashy pictures at Chinese temples).

With the dawning of the foyuan trend, gone are the days of internet celebrities flocking to five-star hotels or top restaurants to take their selfies or vlogs. Now, they head to Chinese temples to pray and give offerings, eat vegetarian food, copy scripture and sip tea instead. However, as with other internet celebrities, foyuans still showcase branded bags and apparel in their photographs, and attach a link in the caption for their followers to buy these products.

...it is a "sin" for droves of influencers to flock into pristine and serene Buddhist temples. While they may seem to be at peace with the world, they are in fact filled with materialistic desires. - Chinese authorities

Workers' Daily, the official newspaper of All-China Federation of Trade Unions, said in a commentary published on 21 September that it is a "sin" for droves of influencers to flock into pristine and serene Buddhist temples. While they may seem to be at peace with the world, they are in fact filled with materialistic desires. The article even said that the various shopping links added to the images are like the various demons in Journey to the West, adding that the fox's tail can never be hidden under a robe. That is, one's true (evil) nature will not go undiscovered under the guise of a Buddhist robe.

While many netizens frown on the behaviour of foyuans, they are equally unhappy that a state media has singled them out as well. They think that speaking of these influencers in the same breath as demons is tantamount to turning the originally neutral term foyuan into a derogatory label stigmatising women. They lamented, "How about the 'greasy' middle-aged men who wear beaded bracelets, drink tea, and pretend to be youthful? Or the numerous "Big Vs" who have a huge following on Weibo and sell products while riding on the massive nationalist wave? Why are they not attacked or criticised?"

...female consumers who are the main driving force behind the pretty boys craze and target audience of foyuans particularly feel that they are being picked on.

Preserving traditional gender roles and family model

While the ban on effeminate men and the criticisms of foyuans may seem like two separate issues, they actually speak of increasing government intervention on the benchmarks of beauty. In addition, female consumers who are the main driving force behind the pretty boys craze and target audience of foyuans particularly feel that they are being picked on.

Chinese women moving towards economic independence are becoming the most active consumer group. Statistics show that in 2020, the total amount of consumption by Chinese women reached 4.8 trillion RMB (S$1 trillion). They also comprise 70% to 80% of all vertical e-commerce users. The market is female-driven, and this has also led to changes in traditional social order and aesthetics.

As China slips into a demographic crisis, an increasing number of young women are choosing to stay single and not get married. They obsess over pretty boys and tanbi drama series about "boys' love". Instead of sacrificing themselves for their family, they would rather focus on their careers and leisure. This is an inevitable trend as society and economy develop, and as women gain greater awareness of their rights and options. This is also a challenge facing those leading the country.

While authorities' concerns over the like economy and the disorderly internet celebrity economy are not unfounded, it will be an increasingly difficult task to realign people's standards of beauty and unify social values. While harsh top-down regulations and guidance may achieve temporary results, they are more likely to trigger stronger and more protracted side effects.