Chinese single women ponder love, marriage and freedom

They are well-educated and economically independent with broad interests - and they are not getting married. Why do women account for the majority of singles in China's big cities? What are their thoughts on marriage and love? Zaobao correspondent Chen Jing explores the world of single women in China.

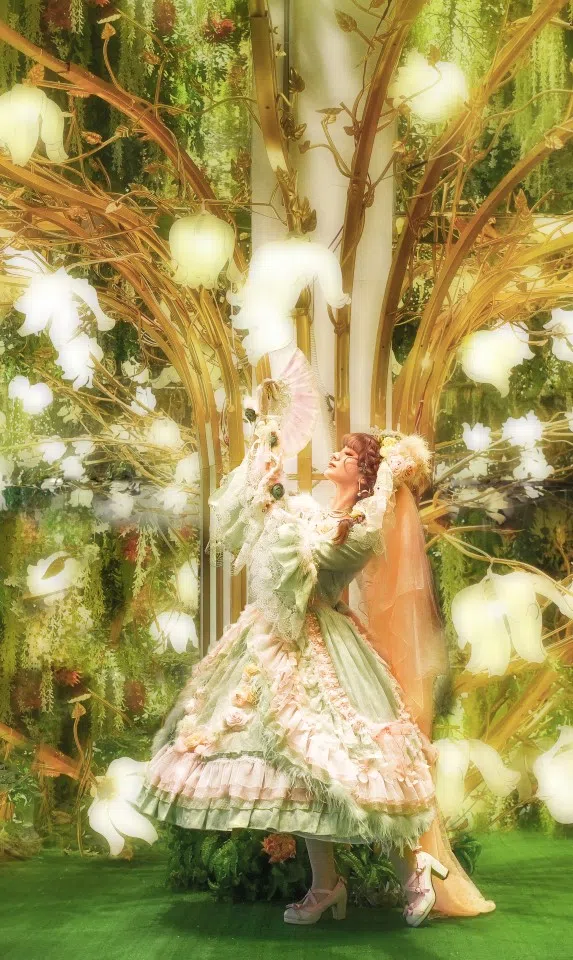

(Photos courtesy of interviewees unless otherwise stated)

"When a man buys a house, he dares to get married; when a woman buys a house, she dares to stay single."

A year ago, 33-year-old Zheng Hong (pseudonym) bought her own home in Shenzhen, cementing her resolve to stay single. For this account manager at a software company, marriage is just an economic contract. "If I'm doing fine on my own, there's no need to get married."

Zheng says in an interview with Zaobao that a few years ago, she dated actively with the aim of getting married, but in recent years, after hearing many stories of unhappy marriages among friends, she is no longer so keen on marriage as she was before. "Guys who seemed like good husbands ended up cheating on their wives! These days, a woman can only expect her husband to be her everyday collaborator, but the pressure shoots up when they have kids."

Zheng's last relationship ended about five years ago, and none of the dates she has had since turned into a long-term relationship. She laments that she's but an extremely busy member of the working class. "I can only meet after 10pm. How can I date?"

"There are too many things to do, and I might have to give them up if I get married." - Zhou Yilian, 33

If marriage is just a practical concern, many would rather not have it

Living in a big city where everyone minds their own affairs, nobody cares whether one is married or not. And while it does get lonely sometimes, there are many things that Zheng can do, such as catching a movie, visiting exhibitions, or getting a facial done. She recently signed up for drawing class, taking the opportunity to make new friends.

Singletons like Zheng are on the rise in China. They are mostly well-educated, financially independent women over 30. They choose not to get married because they believe they can live well without marriage, and because they see more drawbacks than advantages to marriage.

"There are too many things to do, and I might have to give them up if I get married." In our interview with 33-year-old Zhou Yilian (pseudonym), she repeatedly says she is worried that marriage will take away her freedom.

Zhou may seem like an ordinary civil servant from Quanzhou, Fujian, but her WeChat profile reveals her multiple identities: guzheng player, dancer, tailor, and cosplayer. All this started 11 years ago, when she got hooked on Taiwan's Pili glove puppetry show series. Zhou turned up at fan events dressed as characters from the show, and even learnt tailoring, drawing, guzheng, and dancing, in order to better play the character.

She has since gotten to know other Pili fans and found common conversational topics with people her age. She says most of her other friends are married with children, and they no longer share common interests, but she has much to talk about with her newfound online friends.

However, these fans usually stop participating in activities once they get married and have children. Those who can commit are mostly still single, which makes marriage even less desirable to Zhou. She says, "Women tend to devote themselves to family and children after marriage. My married friends all feel they have lost their personal freedom. If I get married and can no longer do what I love, what will become of me?"

Six-year slide in marriage numbers

Falling marriage numbers reflects the attitude shift among the younger generation from wanting to get married to fearing marriage. Figures from the Ministry of Civil Affairs show a six-year slide in marriage rates, from 9.9% in 2013 to 6.6% in 2019. Also, the more economically developed the region, the lower the marriage rate. Shanghai and Zhejiang had the lowest figures in 2018, while figures were also comparatively low in Guangdong, Beijing, and Tianjin.

"The men or in-laws may still expect women to take care of the household chores and the children, and the women have to shoulder the double duty of family and work." - Jean Yeung, NUS

Provost-Chair Professor Jean Yeung of the Sociology Department at the National University of Singapore (NUS) says that with higher education levels, more women are economically independent and marriage is no longer a necessity as it used to be. More women today seek career development, but workplace discrimination against women has not lessened, making it difficult for them to juggle career and marriage. As a result, some choose to delay marriage for the sake of their career. Furthermore, with the convenient facilities and wealth of activities in big cities, people prefer to indulge in entertainment and consumerism, which might also lead the younger generation to delay or even give up on marriage.

Even as marriage rates are dropping, divorce rates are rising, from 2% in 2010 to 3.4% in 2019. Prof Yeung observes that most divorce applications are made by women. "This might be because traditional gender roles cannot keep up with the rising status of women in China," she says. "The men or in-laws may still expect women to take care of the household chores and the children, and the women have to shoulder the double duty of family and work."

Tan Gangqiang, head of a psychology consultation centre in Chongqing (重庆市协和心理顾问事务所), notes that China's urbanisation in recent years has accelerated population movement, so that young people no longer spend all their lives in one city as did the generations before. Having to move around for work and living also leads many people to see marriage as a burden rather than a safeguard; this is particularly obvious in first-tier cities with high population mobility.

"In Shenzhen, everyone is so busy, we never meet. Even if I needed an operation, a husband might not be able to stick around to look after me." - Zheng Hong, 33

Even Zheng, who has bought her own home in Shenzhen, also plans to apply for a transfer to another city in the next year or two, just for a change. As for where she will retire in future, she has no firm answer yet. But she is sure that getting married and having children is not a safeguard for retirement.

"Even though having a partner may mean extra support, but if you get a chronic disease, there is no guarantee that your partner will look after you for decades," she says. "Having children to take care of you in your old age is even more ridiculous. Isn't there a saying not to expect children to be filial when one is ill? I can see our generation living in elderly homes in future, or maybe we'll die suddenly even before that happens. So, instead of worrying about the future, why not live in the present?"

Pressure from parents the biggest headache

Early last year during the pandemic, Zheng worked from home in her hometown of Xiamen for about two months. During this time, not a day went by when her parents did not pressure her to get married - her family even dragged her to a "matchmaking corner" in a park, much to her amusement and chagrin.

Zheng says her mother is bothered by gossip, and is very concerned that the daughter is not yet married. As for Zheng's father who was previously indifferent, he began to worry about her after he got hospitalised - what if his daughter finds herself in the same situation and has no one to attend to her.

Once, when she was buying insurance and considering who the beneficiary should be, her mother chided, "Other people would fill that in with the names of their spouse or children. It's because you don't want to marry, that's why you don't know whose name to write."

But Zheng does not think that marriage is the solution. "In Shenzhen, everyone is so busy, we never meet. Even if I needed an operation, a husband might not be able to stick around to look after me."

After deciding to stay single, Zheng's greatest challenge has been getting her parents to come round to her point of view. She is always on tenterhooks each time they chat, worrying that the subject of marriage will be broached. Once, when she was buying insurance and considering who the beneficiary should be, her mother chided, "Other people would fill that in with the names of their spouse or children. It's because you don't want to marry, that's why you don't know whose name to write."

Apart from constantly reminding her to marry, Zheng's parents also arrange blind dates for her. The candidates often fall short of her requirements and Zheng detests this process, but she is well aware that declining would incur her parents' wrath. Her solution is to give her blind dates the "cold treatment": after adding them on WeChat, she does not chat with them. Even if she does, she would not keep the conversation going for long. Hence, these blind dates eventually become "strangers in her contact list".

While Zheng does not expect to get married or have children, she knows that the pressure will stay as long as she stays single. She sighs, "If I do get married one day, it will definitely be due to the enormous pressure at home."

Thirty-three-year-old Qiao Yi (pseudonym), an architect living in Shanghai, was once in the same predicament as Zheng. Her parents also could not understand her decision and were constantly urging her to marry. Qiao's parents even regretted buying her a house in Shanghai too soon, thinking that if she was without property, she would not be that overqualified in the eyes of her dates, and perhaps be more marriageable.

"Singles are often regarded as aliens, and the strange looks from the public add a lot of pressure on their parents. When they know that this situation is very common in big cities, they will think that this is normal and thus worry less." - Qiao Yi, 33

However, such circumstances changed after her father's short stay in Shanghai. Her father attended a townsmen gathering in Shanghai. When he realised that many men and women of the same age as his daughter were also single, and that Shanghai's population of single women was not in the minority, he began to accept the new reality.

"People in small cities have a more conservative mindset," says Qiao. "Singles are often regarded as aliens, and the strange looks from the public add a lot of pressure on their parents. When they know that this situation is very common in big cities, they will think that this is normal and thus worry less."

Tan suggests that singles pressured by their parents to get married can get trusted relatives or friends of their parents to be intermediaries or enlist the help of experts with a certain level of authority. He once helped older singles to reconcile with their parents, and believes that analysing and providing suggestions from an outsider's perspective is more easily accepted by the elders.

Tan also notes that due to traditional Chinese family values, parents often act on their children's behalf when it comes to marriage. For instance, parents are often the ones gathering in the matchmaking corners of various parks in different regions. He says, "If parents wilfully regard themselves as rescuers of their children's marital status, it would often have a reverse psychological effect on their child. If they can instead engage in deep conversations with their children and understand their attitude towards marriage while thinking of ways to remove their prejudice and misunderstandings of marriage, it could instead alleviate the younger generation's fear of marriage."

No chemistry, no marriage

Li Miao (pseudonym) nearly got married on two occasions, but ultimately rejected both proposals after much consideration because "the chemistry was simply not right".

Of her two suitors, one was rich and had hoped that Li would become a housewife after they wed. But she felt that she did not love him enough, and that resigning and staying home would make her a nanny to her husband. The other suitor made her heart skip a beat, but he turned out to be a playboy. Li was worried that he would continue his flirtatious behaviour after marriage and ultimately rejected him.

"... But there are way too many things that are not up to me in work and life. A relationship is what's left in my control. So just let me stand firm in what I believe in." - Li Miao, 40

Since money and fluttery feelings proved insufficient for Li to walk down the aisle, what exactly is the "chemistry" that Li is searching for? Li says after a pause, "I want everlasting love. I hope that both of us will love and care for each other 100%. Some friends say that I'm too idealistic and that my relationship mindset is still like that of a student's. But there are way too many things that are not up to me in work and life. A relationship is what's left in my control. So just let me stand firm in what I believe in."

Forty-year-old Li is a native of Shanghai and works at a multinational corporation as a product manager. Like most single white-collar workers in Shanghai, she is not worried about living alone and has already made plans to retire together with her friends. However, she goes on blind dates arranged by her friends and family in hope of finding a life partner. "If there is no one suitable, I don't mind remaining single," she says.

However, Li is well aware that her options are decreasing as she grows older, and that the marriage market is disadvantageous to women. She laments, "A man's attractiveness does not decrease as their age increases. Even when they are in their 30s, they can still find a 20-something female. But if women are not married before the age of 25, looking for a partner later on becomes tougher. Besides, an 'A-grade' guy can marry ladies that are A-, B-, C-, or D-grade. But if women marry someone worse off than them, they would be accused of marrying down. The options we have are much less than what's available to men."

Academics say well-educated women find it harder to find a partner

In 2019, statistics from the National Bureau of Statistics of China showed that there were 685 million women - 30 million less than the number of men - in China's total population of 1.4 billion. However, in 2017, the proportion of girls in colleges and universities reached 52.5%, a percentage surpassing that of boys in college and university. Prof Yeung points out that Chinese women generally want to marry men who are better educated and earn more than them. But as women are becoming better educated than men, it is becoming tougher to find a suitable match in the marriage market.

Qiao is aware that her "market value" quickly plummeted after she turned 30. She says, "Most eligible men who are around my age tend to look for women under the age of 30. Those who are willing to meet me are mostly older men or those who are not so eligible."

"Now, even if he's rather short, does not have much hair, or no hair altogether, I would be okay with it. The most important thing is that our values align and our financial abilities match." - Qiao Yi, 33

Qiao says that her life was largely smooth-sailing until she did not get married before she turned 30 like most of her peers. She then participated in matchmaking activities frequently, but was still unable to meet a suitable partner. She questioned if there was something wrong with her character, and even got anxious and depressed.

However, Qiao later realised that she was not the only one and many other outstanding women were still single. She slowly regained her self-confidence. Having amassed experience on the matchmaking market, she is clearer about the type of partner she is looking for and is willing to make compromises. "In the past, I used to think that I was the one being chosen. But in fact, if I was willing to lower my expectations, I would have so many more options," she explains.

Qiao says that she paid too much attention to physical appearance in the past, wishing that her partner was tall and handsome. "Now, even if he's rather short, does not have much hair, or no hair altogether, I would be okay with it. The most important thing is that our values align and our financial abilities match," she says with a chuckle.

"If I don't get to experience married life, I can still enrich my life in other ways." - Qiao Yi, 33

Qiao also clarifies that it is not so much that she does not want to get married but that she has not found someone suitable. While she does not hanker after true love, she still believes in finding someone to journey with. She is clear that marrying for the sake of marrying is a recipe for divorce.

Like many white-collar workers in Shanghai, Qiao travels abroad every year. She has it all planned out: if she is still unmarried ten years later, she will move to another country or work in a completely different field. "If I don't get to experience married life, I can still enrich my life in other ways," she says. Related: Love in the cloud: China's emerging livestream matchmaking industry | Rich and wealthy 'little sisters' are the new driving force of Chinese consumerism | Portrayal of women in Chinese dramas getting more westernised? | A Chinese woman's status and the one-child policy | Chinese women in the 21st century: Finding happiness and meaning in life

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)