What Southeast Asia wants from the impending Biden presidency

ISEAS academics Malcolm Cook and Ian Storey note that Southeast Asia would welcome a Biden administration policy towards Asia that is less confrontational and unilateralist, and firmer and more action-oriented. The region's governments prefer the new US administration to adopt a less confrontational stance towards China and lower US-China tensions. But while they welcome increased US economic and security engagement with the region, they are less enthusiastic about Biden's emphasis on human rights and democracy.

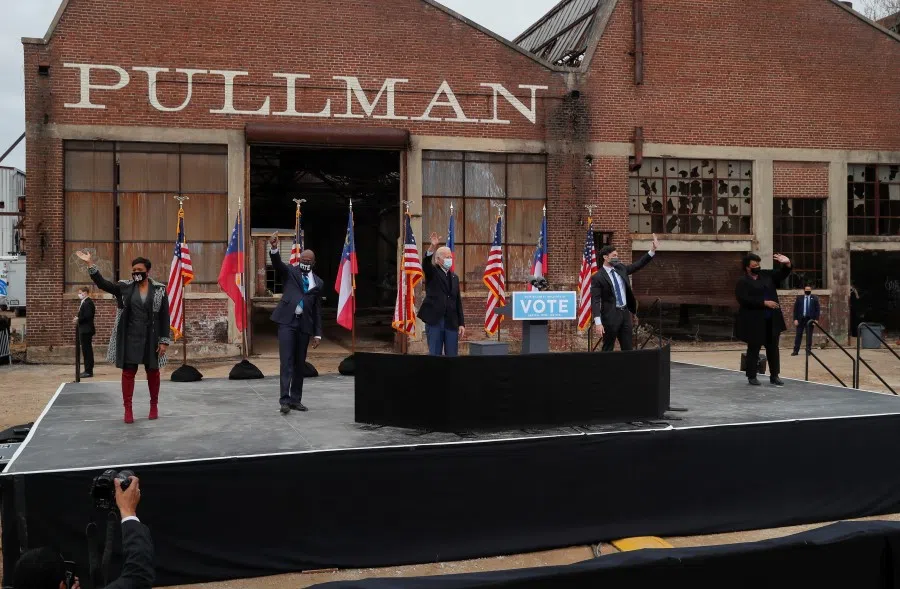

First-term US presidents tend to quickly and clearly differentiate themselves from their predecessors, domestically and externally. This is particularity imperative for President-elect Joe Biden given President Donald Trump's rejection of many mainstream US policy settings and political and presidential norms.

An unhealthy majority of Americans polled believe the country is moving in the wrong direction. International polling suggests that the citizens of key US allies and partners concur. It is not surprising that Biden and his cabinet repeatedly use backward-looking verbs - return, revive, rebuild, reassert - to differentiate themselves from the outgoing Trump administration.

However, the transfer of power's complexities, and domestic policy demands mean that changes to US foreign policy will take time and require patience especially given Covid-19's mounting death toll in America, which could hit nearly 400,000 by the time Biden is inaugurated on 20 January 2021. While Biden clearly defeated Trump, Democrats fared less well. The party's House of Representatives majority shrank, and Republicans will likely retain control of the Senate. Repositioning the Democratic Party for the November 2022 mid-term elections will be its pressing preoccupation.

It is good that the first ASEAN Summit that President Biden can attend will be in mid-November 2021, eleven months after he takes office. By then, the contours of the Biden administration's foreign and security policy should be clearer, its main proponents in place and Biden able to travel the 15,000 kilometres from the White House to Brunei.

Domestic and foreign policy challenges

Domestic issues will be President Biden's top priorities. The incoming administration faces an unusually daunting set of challenges: containing the spread of the coronavirus and implementing a mass vaccination campaign; reviving an economy hit hard by the pandemic leading to mass unemployment; and bridging racial and political divisions.

Its foreign policy agenda is dominated by familiar problems: Afghanistan; the Middle East peace process; North Korea's nuclear weapons programme; and escalating strategic competition with China and Russia. Tackling climate change will also be a signature policy of the Biden administration.

In the first few months, President Biden will emphasise the importance of multilateralism and alliances in addressing some of these foreign policy challenges, and America will cancel its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change, rejoin the World Health Organization, extend the new START nuclear arms reduction treaty with Russia and possibly return to the Iran nuclear deal. Biden will discard Trump's transactional approach to alliances and seek to reassure NATO, Japan and South Korea that his government is committed to America's alliance relationships.

...most Southeast Asians do not want America to be too confrontational nor too accommodating towards China.

The China factor and Southeast Asia

The foreign policy issue that will most affect Southeast Asia is America's future relationship with China. Over the past four years, Sino-US relations have deteriorated significantly over trade, technology, espionage, Covid-19 and China's policies on Taiwan, Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong and the South China Sea. Bilateral relations have sunk to their lowest point since normalisation in the late 1970s.

Southeast Asian countries have been perturbed by the downward spiral in US-China relations and the potentially invidious choices it imposes on them should the strategic rivalry remain unchecked. However, they do not want a return to the Obama-era approach to China which was generally perceived as being weak and ineffective. In short, most Southeast Asians do not want America to be too confrontational nor too accommodating towards China.

President Biden's China policy may go some way towards assuaging regional anxieties. As a candidate, Biden promised to "get tough with China" through a united front with allies and partners while at the same time strengthening cooperation with Beijing over issues where US-China interests converge, especially climate change, global health issues and nuclear non-proliferation. While Biden has spoken of the need for a strong military, he has stressed that diplomacy should be "the first instrument of American power".

The Biden administration will maintain the tempo of freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) and continue to challenge China's actions and jurisdictional claims. As before, some Southeast Asian countries will welcome this, others will not.

Under President Biden, there will be no "reset" in US-China relations nor a return to the policy of "constructive engagement" which is now generally viewed in America as having failed. Biden will find it very difficult to reverse many of the Trump administration's hardline initiatives towards China. Yet his administration is likely to be less confrontational towards China: in the words of David Lampton, "tough without being egregiously provocative". A seemingly good personal relationship forged between Biden and President Xi Jinping during the Obama era may improve the mood music between the two superpowers.

Whether the Biden administration adheres to its predecessor's "Free and Open Indo-Pacific" policy remains to be seen. But even if the name changes, Biden's Indo-Pacific policy will likely retain many of the same approaches to the region, including increasing America's military presence and strengthening alliances and partnerships. US policy towards the South China Sea dispute is unlikely to change very much. The Biden administration will maintain the tempo of freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) and continue to challenge China's actions and jurisdictional claims. As before, some Southeast Asian countries will welcome this, others will not.

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia offers a number of positives for the Biden administration. Recent policy elite polling reflects America's enduring soft power resources in Southeast Asia, and the widespread presumption that President Trump's successor will improve US engagement with the region.

Dr Satu Limaye, vice-president of the East-West Center, views Southeast Asia as a particularly important and conducive region for the Biden administration to put into action much of what it has foreshadowed in foreign policy. This includes a return to the application of predictability and professionalism in the conduct of foreign policy through the appointment of ambassadors, attendance at key events, active support for multilateralism, a less tariffs-based and deficit-focused approach to trade policy and American leadership in the global response to climate change.

In other areas though, there may be more resistance than welcome, including: overt attempts to lead in Southeast Asia; placing democracy and human rights at the centre of American foreign policy; the planned Summit for Democracy that seeks to "honestly confront nations that are backsliding, and forge a common agenda"; the inclusion of stringent labour rights and environmental clauses in trade deals; and defence requests that could spark a Chinese backlash such as hosting a reactivated US Navy 1st Fleet or intermediate-range missiles.

The proposed centrality of democracy and human rights could impinge upon the Biden administration's re-engagement with Southeast Asia. According to Freedom House, in Southeast Asia, six countries are "not free" (Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam), four are "partly free" (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore) while none are "free". In 2020, the 'freedom' scores of Cambodia, the Philippines and Indonesia worsened.

Brunei and Cambodia are the 2021 and 2022 chairs of ASEAN respectively. In 2024, the last year of President Biden's first term, Laos, with Freedom House's lowest score in Southeast Asia, will be ASEAN chair. Will President Biden want to be Hun Sen's guest or that of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party leaders?

With regard to the ASEAN-led mechanisms that include the US, Southeast Asian states should expect or ask from the Biden administration:

• To appoint a senior-level ambassador to ASEAN. ASEAN has gone without a US ambassador for the entire Trump presidency;

• President Biden to attend each East Asia Summit (EAS) and ASEAN-US Summit meeting and for Secretary of State Antony Blinken (if confirmed) to attend each ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and EAS Foreign Ministers meeting. President Trump missed all four EAS meetings and the last three ASEAN-US Summits;

• To ensure that the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (or Quad) involving the US, Japan, India and Australia does not challenge ASEAN's central role in the regional security architecture;

• That the US consider joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) or even the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) when it becomes open to more members.

However, the Singapore government did not shy away from criticising certain aspects of the Trump administration's China policy and seeming loss of appetite for global leadership. While Singapore does not speak for Southeast Asia, its message resonated across the region.

Bilateral relations

As with any US administration, Southeast Asian countries supported some of President Trump's policies and actions while others were less well received. This pattern will be repeated over the next four years. In general, Southeast Asian states favour closer economic engagement with America, support the US military presence but want to see a lowering of US-China tensions. All ten countries are unenthusiastic about the Biden administration's emphasis on human rights and democracy promotion.

Singapore

Although Singapore was disappointed with Trump's withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, bilateral relations have strengthened over the past four years. In 2018, Singapore hosted the first summit between President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. In 2019, Singapore and America extended for another 15 years the 1990 agreement which gives US armed forces access to Singapore air and naval bases. However, the Singapore government did not shy away from criticising certain aspects of the Trump administration's China policy and seeming loss of appetite for global leadership. While Singapore does not speak for Southeast Asia, its message resonated across the region.

In his congratulatory message to President-elect Biden, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said he welcomed "the global leadership of the United States" to overcome challenges such as the Covid-19 pandemic. He also emphasized the strong economic ties between the two countries and Singapore's continued support for America's military presence which "remains vital for peace, stability and prosperity in the Asia-Pacific". In a media interview, Lee expressed the hope that the Biden administration would cultivate an "overall constructive relationship" with China to develop common interests and avert a "collision" between the two superpowers. On Biden's coalition of democracies, he warned that "not very many countries would like to join a coalition against those who have been excluded, chief of whom would be China" and that he did not think a "Cold War style" line-up was likely. He expressed doubt that America would join the CPTPP. Overall, Singapore will continue to support a deepening of America's economic and security engagement with Southeast Asia but caution the Biden administration against a confrontational policy towards China.

In accordance with the country's nonaligned foreign policy, Indonesia endeavours to maintain balanced relations with both the US and China.

Indonesia

US-Indonesia relations under Trump were mixed. Jakarta looked askance at the Trump administration's ban on travel from some Muslim countries and its decision to move the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Although Jakarta has been alarmed at illegal Chinese encroachments into its waters around the Natuna Islands in the South China Sea, it has also been uncomfortable with the Trump administration's hardline rhetoric towards Beijing. China is Indonesia's largest trade partner and second largest investor, and President Joko Widodo (aka Jokowi) is a supporter of Chinese-funded infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In accordance with the country's nonaligned foreign policy, Indonesia endeavours to maintain balanced relations with both the US and China. Before the election, Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi stated that Indonesia did not want to get "trapped" by US-China rivalry. As such, in 2020 Jakarta reportedly rejected a US request to rotate P-8 Poseidon military surveillance aircraft through Indonesia. Nevertheless, defence cooperation between the US and Indonesia improved during Trump's presidency.

Under President Biden, Indonesia hopes to see a more cordial and productive relationship between Washington and Beijing. The world's largest Muslim-majority country will expect the Biden administration to adopt a more impartial stance towards the Israel-Palestine conflict. President Jokowi will encourage the US to increase investment in Indonesia, particularly in the country's infrastructure. Indonesia will also expect more medical support from America to tackle the country's worsening Covid-19 outbreak. The Biden administration itself will continue to court Indonesia in an effort to undercut China's growing influence. US criticism of human rights violations - especially in Papua - and democratic regression in Indonesia could put some strain on the relationship.

Malaysia

Under Trump, US-Malaysia relations were lukewarm. Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad (May 2018 to March 2020) called Trump's decision-making "inconsistent", heavily criticised his administration's decision to move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and even called on the President to resign. Mahathir's government was not supportive of the Trump administration's harder line against China in the South China Sea, warning that a confrontation between US and Chinese warships could spark a conflict.

On Biden's election victory, Mahathir's successor, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin, said that he looked forward to strengthening the US-Malaysia partnership. As with Indonesia, Malaysia will be looking to the Biden administration to pursue a more even-handed approach to the Israel-Palestine problem. Malaysia's concerns about US-China tensions in the South China Sea will persist.

Thailand

Following the 2014 coup, the US downsized defence engagement activities with Thailand and called on the junta to restore democracy. Under President Trump, US-Thai relations were fully normalised, including the lifting of the ban on US arms sales to Thailand. Coup leader Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha's meeting with Trump at the White House in October 2017 was widely perceived in Thailand as a major positive turning point in the post-coup relationship. Nevertheless, Thailand was uncomfortable with the Trump administration's characterisation of China as a strategic competitor and with escalating US-China rivalry. Although Thailand is a treaty ally of the US, it has forged close economic, political and defence ties with China.

Under President Biden, US-Thai relations may struggle to gain traction. Bangkok will oppose increased US scrutiny of Thailand's domestic situation, especially at a time when protesters are calling for greater democratisation and reform of the political system and the monarchy. Another military coup would be a major setback for bilateral relations and result in the re-imposition of US sanctions and even closer Sino-Thai relations. As Thailand looks primarily to China to help rescue its Covid-19 battered economy, it will be wary of any attempt by Biden's Pentagon to strengthen the US-Thai alliance in ways which Beijing may perceive as being aimed at it. As with its two predecessors, the Biden administration will be frustrated by the continued momentum in Thai-China defence cooperation. In short, the US-Thai alliance will continue to experience drift despite attempts by Washington to reinvigorate it.

The Philippines

America's relationship with the Philippines, a treaty ally and a former colony, is its most complicated relationship in Southeast Asia. The last months of the Obama administration overlapped with the first months of the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte. The Obama administration's criticisms of Duterte's signature 'war on drugs' led to a crisis in bilateral, particularly presidential, relations and serves as a warning for the Biden administration's human rights agenda.

President Trump, who praised Duterte's war on drugs, helped steady bilateral relations. Economic relations progressed with Manila and Washington beginning negotiations for a free trade agreement in late 2018. The stabilisation of presidential relations and US concerns with Duterte's overt embrace of China contributed to significant American assistance to the Philippines in its Covid-19 struggles. On the defence front though, in 2018, Manila called for a review of the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty, while President Duterte's February 2020 decision to cancel the 1998 Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) with the US is currently only suspended and not withdrawn.

From January 2021 to June 2022, the Biden administration will overlap with the end of the single six-year term of President Duterte. Bilateral trade talks will likely not progress, and defence relations could worsen significantly - including the termination of the VFA in August 2021 - if the Biden administration criticises the Duterte administration's woeful human rights record.

Brunei

Brunei's chairmanship of ASEAN in 2021 will provide US leaders with an opportunity to visit the country, subject to the Covid-19 situation. If ASEAN-led forums do take place in person, Secretary of State Blinken will travel to Brunei mid-2021 to attend the ARF, and President Biden in November for the EAS. If Biden attends the EAS in person it will be the first visit by a sitting US president to Brunei since President Bill Clinton attended the APEC Summit in November 2000. The Biden administration may raise human rights issues with Brunei, including shariah law, but this is unlikely to negatively impact relations.

However, Vietnam does not want to see an overtly confrontational relationship develop between its two largest trade partners or to be dragged into an armed conflict in the South China Sea.

Vietnam

Overall, US-Vietnam relations did very well under Trump. On the downside, Hanoi regretted the president's decision to withdraw from TPP - Vietnam stood to gain the most from America's participation - and rejected US accusations of currency manipulation and unfair trade practices. On the upside, Vietnam was pleased with the Trump administration's tougher stance towards China in the South China Sea, and growing US-Vietnamese defence cooperation (Vietnam participated in the annual Rim of the Pacific naval exercises for the first time in 2018 and US aircraft carriers visited Vietnamese ports in 2018 and 2020). Hanoi was also supportive of the Trump administration's US-Mekong Partnership and Blue Dot initiatives.

Although some Vietnamese expressed disappointment with Biden's victory, bilateral relations are likely to advance further over the next four years. The Biden administration will continue to pursue tough policies towards China, including in the South China Sea where Hanoi and Beijing have overlapping territorial and jurisdictional disputes. However, Vietnam does not want to see an overtly confrontational relationship develop between its two largest trade partners or to be dragged into an armed conflict in the South China Sea. The Vietnamese leadership hopes to see stronger US diplomatic efforts in the Mekong region. Hanoi will want to see the Biden administration drop investigations into its currency and trade practices. While US-Vietnam military ties have the potential to expand further, with more exercises, warship port calls and possibly even US arms sales to Vietnam, US criticism of Hanoi's human rights record may limit this.

Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos

Major changes in America's relations with Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos are unlikely under the Biden administration. Washington will continue to seek to promote human rights and democracy in all three countries while at the same time try to offset China's considerable, and growing, economic and political influence in Naypyidaw, Phnom Penh and Vientiane as well as over Mekong River governance issues.

The Biden administration will encourage democratic consolidation in Myanmar and a resolution of the Rohingya problem. Washington will continue to enforce Trump-era sanctions against Cambodia absent democratic reforms which Prime Minister Hun Sen is unlikely to introduce. As a result, Cambodia will be pulled further into China's orbit. The establishment of Chinese military logistic facilities in Cambodia would put further strain on US-Cambodia relations. Laos will not be high up on the new administration's Southeast Asia agenda, though President Biden may visit the country during its 2024 chairmanship of ASEAN.

Looking forward

In Southeast Asia, the Biden administration-in-waiting's pronouncements that it will revive traditional US foreign policy settings and behaviour will be welcomed, and its future actions will be judged by this yardstick. However, any signs that there is a desire to return to the settings and behaviour of the Obama administration will cause consternation. Southeast Asia's strategic environment and America's position in it have changed irreversibly since 2016. The Biden administration will have to quickly locate and maintain the medium between reviving the US position and practices in Southeast Asia and not being perceived as seeking a return to an era that no longer exists.

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2020/143 "The Impending Biden Presidency and Southeast Asia" by Malcolm Cook and Ian Storey.

Related: America needs to value Southeast Asia for its own sake, and not just as a tool to fight China | Now more than ever, Southeast Asia values a firm American security presence | Overzealous attempts by China and the US to sway Southeast Asia countries counterproductive | How a Biden presidency can win back lost American influence in Southeast Asia