How the Iran-Israel conflict is rewriting China’s global playbook

The Iran-Israel conflict and subsequent US intervention have compelled China to rethink its geopolitical approach in the Middle East. But such a recalibration will be difficult, says commentator Imran Khalid, as Beijing must be able to balance its energy demands and economic ambition with security interests.

Twelve days of escalating hostilities and heightened regional tension ended on 24 June with a ceasefire that is already fraying. From Washington and Jerusalem came declarations of triumph; in Tehran, vows of revenge. Yet perhaps the most consequential reaction unfolded quietly in Beijing, where policymakers asked a pressing question: what does this renewed volatility in West Asia mean for China’s interests and for the evolving multipolar order that Beijing seeks to shape?

Within hours of the US-Israel strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities in Fordow, Natanz and Esfahan, the Chinese foreign ministry condemned the attack as a serious violation of national sovereignty and called for maximum restraint from all sides.

An emergency United Nations Security Council debate followed, initiated in part by China’s diplomatic efforts. Though the outcome was inconclusive, the intention was clear: to reaffirm the primacy of the United Nations and international law, both of which are central tenets of Beijing’s global diplomatic framework.

Beyond legal principles, energy security shaped China’s response. Nearly half of China’s crude oil imports are sourced from the Gulf region. Following Washington and Israel’s weekend attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities, oil prices surged to their highest level since January. Prediction markets, citing Polymarket data, indicated a 52% probability of Iran closing the Strait of Hormuz this year, a vital waterway for about a fifth of global oil consumption. Chinese refiners quickly hedged shipments, prompting Beijing to offer diplomatic support to maintain the fragile ceasefire.

A shifting security order

At the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s defence ministers’ meeting in Qingdao on 25 June, China’s evolving role as a potential conflict mediator was brought into sharper focus. While China’s 2023 success in brokering a rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia boosted its diplomatic confidence, the Qingdao gathering underscored existing limitations.

Talks failed to produce a joint communique after India objected to language condemning unilateral military actions by the United States, demonstrating the complexity of forging regional consensus. This recognition is likely to reinforce Beijing’s cautious strategic posture — prioritising economic integration and political neutrality over direct involvement in regional conflicts.

The crisis also reinforces the relevance of the Global Security Initiative and the Global Development Initiative — Beijing’s signature frameworks for sustainable and inclusive global governance.

This development reignites concerns about the possibility of a regional nuclear arms race — an outcome that would threaten the stability of Belt and Road Initiative corridors from Gwadar to Piraeus.

Complicating matters further, Iran’s parliament voted unanimously on 25 June to suspend cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency and to expel inspectors until those responsible for the strikes are held accountable. The bill was approved by the Guardian Council, a body tasked with vetting legislation, on 2 July before it would receive final ratification from the presidency. This development reignites concerns about the possibility of a regional nuclear arms race — an outcome that would threaten the stability of Belt and Road Initiative corridors from Gwadar to Piraeus.

Regional media have recently begun discussing the concept of a Gulf-wide collective security mechanism involving regional players such as Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, while excluding outside military powers. This concept, though yet to gain formal backing from other major stakeholders, could gain traction as middle powers in the region seek more localised and less militarised solutions to regional security challenges.

Meanwhile, remarks by US President Donald Trump at the NATO summit in The Hague raised eyebrows in the region. His dramatic framing of the strikes raised debate over historical analogies, and his statements were contradicted by leaked US intelligence assessments suggesting that Iran could resume 60% uranium enrichment within months.

This dissonance between rhetoric and reality has not gone unnoticed. It reinforces concerns about the unpredictability of US foreign policy, and adds weight to calls for an independent and Asia-centred security architecture, as well as for the accelerated de-dollarisation of critical trade sectors such as energy.

The broader strategic takeaway from China’s response is its approach of disciplined distance and selective engagement... this very restraint has enabled Beijing to position itself as a stable, principled actor in contrast to Washington’s more militarised approach.

China’s Middle East advantage: restraint pays off

Beijing is now assessing several possible outcomes. Should the ceasefire evolve into negotiations, as some US and Iranian officials have hinted, there may be space to revisit the concept of a Gulf nuclear fuel consortium — an idea quietly supported by China. In such a scenario, Beijing could present itself as an indispensable facilitator and credible guarantor of a future inspections regime.

Alternatively, if Tehran’s hard-liners prevail and nuclear enrichment proceeds behind closed doors, Beijing will face a delicate balancing act: defending its non-proliferation commitments while maintaining support for a critical partner in its energy strategy.

A third scenario, regional proxy escalation, could see groups such as Hezbollah taking retaliatory action, potentially drawing the US into a long-term policing role in the Gulf. While such a diversion might seem advantageous from a narrow Indo-Pacific perspective, Chinese economists warn that oil-price volatility could severely disrupt growth projections for 2025.

The broader strategic takeaway from China’s response is its approach of disciplined distance and selective engagement. China’s influence in the Middle East remains asymmetrical, marked by substantial economic presence but limited military reach. Yet this very restraint has enabled Beijing to position itself as a stable, principled actor in contrast to Washington’s more militarised approach. That perception, especially across the Global South, where memories of unilateral interventions remain vivid, enhances China’s soft power and credibility.

Beijing is likely to fast-track the development of renminbi-settled crude futures on the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange.

Domestically, this crisis will likely accelerate two policy tracks. First, China is expected to increase investment in overland energy routes that bypass maritime chokepoints like Hormuz, including projects under the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor and new China-Central Asia pipeline expansions, as well as possible rail links from Iraq to the Mediterranean.

Second, Beijing is likely to fast-track the development of renminbi-settled crude futures on the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange. This would reduce vulnerability to US financial instruments during oil shocks and bolster the renminbi’s standing in international energy markets, building on recent yuan-denominated trade settlements with Gulf nations such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

China recalibrates its geopolitical strategy

Perhaps most importantly, the conflict has prompted a recalibration of strategic assumptions. Chinese military planners increasingly operate under the belief that the US remains willing to deploy overwhelming force abroad if it believes its deterrent credibility is at stake.

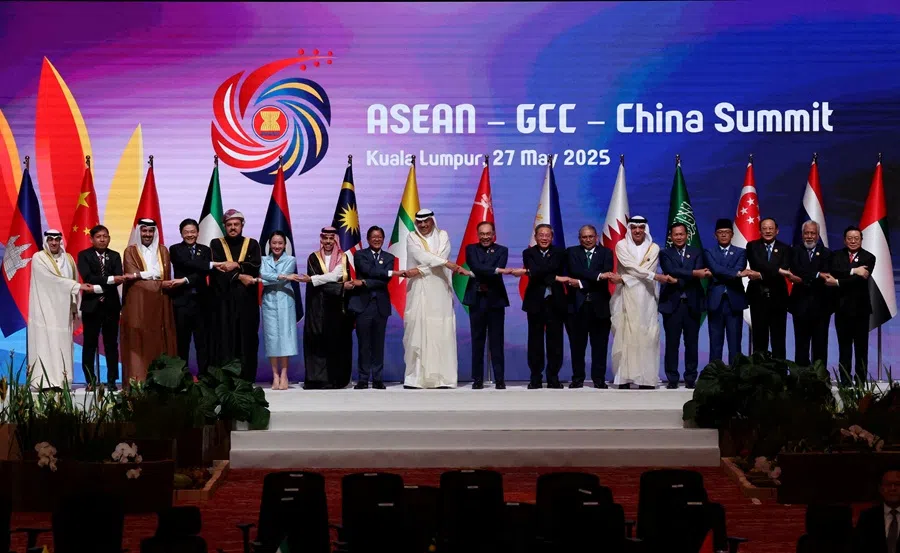

This realisation will shape Beijing’s posture in other sensitive theatres, including the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea, compelling Beijing to enhance its diplomatic outreach, particularly to ASEAN and Gulf nations. The template is becoming clear: strong signalling backed by deepened economic and political engagement.

In a region where conflicts often outpace reconciliation, the role of a patient architect may prove more enduring than that of a bold demolisher.

When the smoke cleared over Natanz and Jerusalem, no side could claim a decisive victory. The US disrupted but did not destroy Iran’s nuclear capabilities. Tehran’s missile barrage may have satisfied domestic political imperatives, but it left its economy further isolated. Israel’s pre-emptive strike may yield only temporary calm. China, though untouched militarily, has been compelled to re-evaluate its assumptions and recalibrate its strategy.

That recalibration is not driven by adventurism, but by prudence. China’s approach has emphasised measured diplomacy, economic engagement, and strategic patience. In a region where conflicts often outpace reconciliation, the role of a patient architect may prove more enduring than that of a bold demolisher. And it is this measured but strategic engagement that increasingly defines Beijing’s approach to global crises.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)