[Big read] Durians, tea and livestreams: Can rural China power its 2035 modernisation dream?

Durians and livestreaming are boosting China’s rural economy, but can border trade compete with established hubs? Experts weigh in on the challenges of revitalising remote areas, from corruption to talent drain, as China aims for modernisation by 2035. Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Sim Tze Wei reports from Malipo county on the China-Vietnam border.

The minibus pulled into the Tianbao Port international cargo yard in Malipo county, near the China-Vietnam border. The familiar smell of Southeast Asia’s “king of fruits” — the durian — hit me the moment I got off the bus.

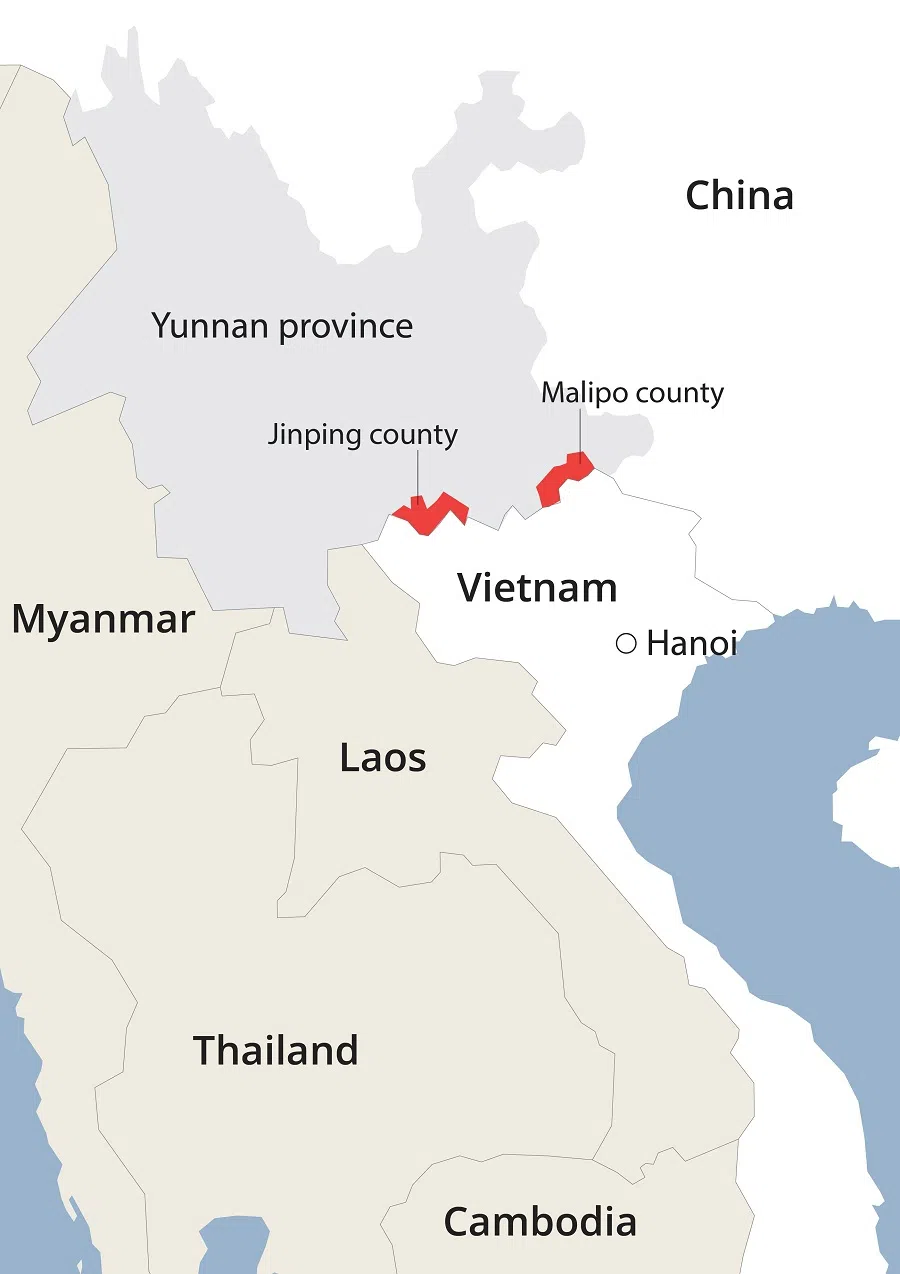

In early May, I, along with five other Beijing-based foreign correspondents, visited Malipo and Jinping in Yunnan province’s Wenshan Zhuang and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, on a five-day media trip organised by the Chinese foreign ministry.

Pointing to where large trucks were parked in the international cargo yard, Xiao Changju, Malipo deputy party secretary and county magistrate, said to us with a smile, “Smell the durians?”

Officially opened last August, the Tianbao Port international cargo yard accommodates up to 1,500 vehicles per day. Xiao explained that an average of one to two hundred large trucks currently transit there daily, most of which are waiting to transport Thai and Vietnamese durians imported from Vietnam.

It is the shortest land route from Yunnan to Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital.

Tianbao Port’s history

Tianbao Port is located in Tianbao Town, at the foot of Laoshan Mountain in Malipo, and is connected to the Thanh Thuy border gate in Ha Giang province, Vietnam. It is the shortest land route from Yunnan to Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital.

Laoshan is a name deeply etched in the memories of middle-aged Chinese. In February 1979, China launched what it called a “self-defensive counterattack” against Vietnam (known in Vietnam as the “Northern Border Defence War”). Subsequently, numerous border clashes occurred, and conflict broke out at Laoshan in Malipo in 1984. The Battle of Laoshan (known in Vietnam as the Battle of Vị Xuyên) lasted for about ten years, with Laoshan becoming the frontline of the conflict between the Chinese and Vietnamese armies.

Under the shadow of war, Tianbao Port was closed for an extended period. It was not until November 1991, that the longstanding hostility between China and Vietnam ended, after a meeting between then-General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party Do Muoi and then-Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Jiang Zemin. Two years later, in 1993, Tianbao Port was reopened.

From battlefield to border market

While other Chinese provinces rode the wave of reform and opening up, Malipo and Jinping, located on the frontline of the war, lost at least a decade’s worth of crucial development time.

After the war subsided, Malipo and Jinping received targeted assistance from the Chinese foreign ministry, starting in 1992. In May 2020, they successfully eradicated absolute poverty and shed their designation as impoverished counties.

The former mine-laden battlefield has now become a border market between China and Vietnam.

According to official data, the per capita disposable income of urban residents in Malipo reached 37,299 RMB (US$5,177) last year, a year-on-year increase of 4.3%. Meanwhile, the per capita disposable income of rural residents reached 16,679 RMB, a year-on-year increase of 7.4%. In 1992, the per capita net income of farmers was only 226 RMB.

The former mine-laden battlefield has now become a border market between China and Vietnam. When the media delegation arrived at the market near the border crossing around 9 am, border residents selling coconuts explained that the Vietnamese coconuts had sold out, and the ones displayed on the ground were from Hainan.

Liu Jun, the owner of a restaurant and Vietnamese goods wholesale store near the border crossing, said her business has always been good, “except during the pandemic”. However, I observed that shops in the less desirable second row saw sparse foot traffic and sluggish sales.

Durian remains king of fruits in China

Despite China’s persistently weak domestic consumption, demand for durian remains strong.

Wang Yinghuai, deputy secretary of the Party Working Committee of the Malipo border economic cooperation zone, told the media that Tianbao Port has become China’s third-largest durian-import port since it was approved to import durians last year. As of 7 May, 27,000 tons of durian have been imported, with a value of 830 million RMB.

... a daily average of 50 trucks carrying Thai and Vietnamese durians enter Malipo from Vietnam’s Ha Giang province through Tianbao Port, before being distributed across China.

He said that a daily average of 50 trucks carrying Thai and Vietnamese durians enter Malipo from Vietnam’s Ha Giang province through Tianbao Port, before being distributed across China. Regarding media concerns about whether Malipo’s border trade was affected by the China-US trade war, Wang emphasised that they have felt “absolutely nothing”.

Xiao said, “Residents are still enjoying their square dancing, and trade remains unaffected. In fact, it has even seen a significant boost thanks to durian.”

Responding to questions from Beijing-based foreign media regarding China-US tariff negotiations, Vice Foreign Minister Hua Chunying confidently asserted, “As you can see, people have full confidence in our capability to overcome all the difficulties.”

This also marked Hua’s first visit to Malipo and Jinping in her capacity as head of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ leading group for targeted poverty alleviation in rural areas.

Official data shows that the import and export value of Malipo from January to 5 May reached 1.37 billion RMB. This exceeds the 1 billion RMB target and marks a record year-on-year increase of 66%.

...once the policy for sturgeon export to Vietnam is implemented, the county government will be able to encourage villagers to increase sturgeon farming for export to boost their income. — Xiao Changju, Malipo Deputy Party Secretary and County Magistrate

Diversifying imports

Xiao also mentioned that following the durian boom, they hope to secure imports of high-value products such as seafood and bird’s nest from Vietnam in the future. The Chinese market for bird’s nests not only has high demand but also has a higher value than durian.

The expansion of the list of import and export categories at the port largely depends on bilateral relations between China and Vietnam. To Lam, general secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam, chose China for his first official visit abroad after taking office last August. Similarly, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping also chose Vietnam for his first overseas visit this year. Following Xi’s visit to Vietnam in April, the China-Vietnam joint statement included a commitment from Vietnam to “accelerate the import of sturgeon from China”.

Xiao said that once the policy for sturgeon export to Vietnam is implemented, the county government will be able to encourage villagers to increase sturgeon farming for export to boost their income. Currently, Malipo’s exports to Vietnam include aluminium wires and bars.

15 kilometres away from Tianbao Port, the rural revitalisation demonstration park houses an agricultural product processing zone. Some primary agricultural products imported from Vietnam, such as chilli peppers, rice noodles, and dried fruits, are processed here into value-added products like freeze-dried snacks, which are then sold to domestic and overseas markets. The media delegation was told that the park achieved a total output value of 57 million RMB last year.

Xiao explained that border trade effectively increases the income of border residents, who are exempt from taxes on goods worth up to 8,000 RMB per day. These imported goods can be sold to companies for processing, allowing residents to profit from the price difference — “what we call staying on the border and profiting from the border”.

How do Malipo residents feel looking back on the Sino-Vietnamese border war in light of the current border trade interactions? Xiao responded, “Look at history objectively and face the future. We are all looking forward, and so are they.”

Although Malipo is actively developing its border trade, academics interviewed are not optimistic about its prospects as they believe it will struggle to compete with Guangxi.

Border trade limited by underdeveloped transport networks

Although Malipo is actively developing its border trade, academics interviewed are not optimistic about its prospects as they believe it will struggle to compete with Guangxi.

Li Mingjiang, an associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), thinks that Guangxi can transport large quantities of durian from Thailand and Malaysia — as well as various tropical fruits from Southeast Asian countries — to China via the Port of Beibu Gulf and the New International Land-Sea Trade Corridor. Meanwhile, the border counties in Yunnan that rely solely on land transportation “simply cannot compare”.

An unnamed Chinese international relations expert pointed out that the regions adjacent to the China-Vietnam border are underdeveloped and remote on both sides, resulting in “relatively limited market capacity”. There is no direct rail access to Malipo, and the expressway connecting to the national border crossing is not yet completed. Thus, it currently lacks a transportation advantage for distributing goods imported from Vietnam to other parts of China.

Poverty alleviation

Malipo has a population of approximately 233,000; 99% of the county is mountainous, while over 70% is covered by karst topography. Farmers lack flat land for cultivation, and economic development has been difficult.

This reminded me of a 2012 trip to Qinglong county in Guizhou’s Qianxinan Buyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture. I had reported on rural poverty alleviation during the trip, which also involved traversing mountainous karst terrain. The biggest difference between the two trips was that in 2012, the media visited numerous rural households under official arrangements and heard heartbreaking stories, such as families who were once “so poor they only had two sets of clothes”.

The contrast between these two trips reflects the tremendous transformation of rural China over just 13 years — from poverty alleviation to rural revitalisation.

This time, instead of visiting individual rural households, I visited businesses, border crossings and new rural villages to gain a first-hand understanding of China’s rural revitalisation efforts. I also heard more inspiring stories on the journey towards prosperity.

The contrast between these two trips reflects the tremendous transformation of rural China over just 13 years — from poverty alleviation to rural revitalisation.

Rural revitalisation: top-down plan

Xi officially declared complete victory in the fight against absolute poverty on 25 February 2021. However, this is not the end goal. Poverty alleviation and rural revitalisation may seem separate, but they are actually interconnected. To prevent a return to poverty, rural areas must continue to create wealth through industrial development.

The Chinese government’s plan on all-round rural revitalisation for the 2024-2027 period emphasises improving the standard of rural industrial development, rural construction and rural governance. The plan also highlights the dual drivers of technology and reform and strengthens measures to increase farmers’ income. It also promotes the “five revitalisations”: rural industries, talent, culture, ecology, and organisation.

In recent years, the CCP Central Committee’s “No. 1 central document” has specifically stressed the need to adapt to local conditions and develop “speciality products”, increasing their value-addedness and transforming them into major industries for farmers to increase their income.

After comparing these policies with the observations made during the media trip, it is evident that both Malipo and Jinping have been implementing the guidelines outlined in these official documents over the past two years.

Hong Kong-based Sunwah Group invested 50 million RMB to establish a 5,000-square-metre modern tea factory in Malipo, which began operations in 2023.

Tea processing in Malipo

For instance, Malipo focuses on tea processing, capitalising on its location within the 23rd parallel north — a prime tea-producing region. Interestingly, Laoshan, a mountain that once witnessed intense battles, has even become the brand name for the annual Malipo International Spring Tea Festival. At the invitation of the Chinese foreign ministry, Hong Kong-based Sunwah Group invested 50 million RMB to establish a 5,000-square-metre modern tea factory in Malipo, which began operations in 2023.

Jason Choi, the 25-year-old director of Sunwah Group, told the media that the tea factory directly employs over 100 people. It has created 10,000 job opportunities in total, including upstream and downstream stakeholders such as tea farmers and cooperatives. A major challenge in running the factory is the generally low level of education among tea farmers, coupled with a weak awareness of hygiene and environmental protection. Farmers thus need constant reminders to wash their hands frequently, wear masks, and protect ancient tea trees. “This process is very difficult,” Choi admitted.

In Jinping’s Mengla town, about a four-hour drive from Malipo, an agricultural product industrial project integrating production, processing, and sales has been established. Through an order-based planting model that integrates “company + village collective + cooperative + farmer”, it guides surrounding farmers to cultivate small-flower waxy corn, thus helping to stabilise their income.

In Manpeng New Village, Jinshuihe Town, predominantly inhabited by the Miao people, villagers have embraced livestreaming, transforming themselves into livestreamers to increase awareness of local specialties and convert online traffic into sales.

Livestreaming to boost awareness

This project, with an investment of 110 million RMB by Shijing Agricultural Technology, began operations in July 2023 and employs approximately 300 people. Ruan Quan, general manager of Shijing Agriculture, explained that the parent company is Shenzhen-based Colourful Technology. Leveraging their strong technological foundation, they utilise Internet of Things (IoT) and blockchain technology to track agricultural products through every step, from planting and processing to transportation and sales. “The entire process from soil to shelf is transparent, giving consumers peace of mind,” Ruan said.

In Manpeng New Village, Jinshuihe Town, predominantly inhabited by the Miao people, villagers have embraced livestreaming, transforming themselves into livestreamers to increase awareness of local specialties and convert online traffic into sales. We were told that Manpeng New Village achieved livestream sales of 28.3 million RMB last year, increasing farmers’ income by 3.91 million RMB.

However, Huang Huiqiong, a villager who does embroidery, told reporters that while livestreaming has increased per capita annual income by about 2,000 RMB, “it’s not enough and it’s impossible to rely solely on livestreaming. We still have to continue growing rubber and working on the farm”.

Rural revitalisation important for achieving modernisation by 2035

It was clearly stated at the CCP’s 19th Party Congress that the country will see the basic realisation of socialist modernisation by 2035. The success of rural revitalisation will play a crucial role, and the next ten years will be a critical period for advancing rural modernisation.

An unnamed Chinese political academic told Lianhe Zaobao that after rural areas were lifted from absolute poverty and basic needs for food and clothing were addressed, the CCP formulated the overall strategic goal of rural revitalisation, aiming to narrow the rural-urban gap through rural development.

“From this perspective, rural revitalisation is certainly very important for China to achieve modernisation by 2035. Failure to achieve rural revitalisation would hinder progress towards the 2035 goal,” the academic said.

According to China’s seventh national census conducted in 2020, more than 500 million people live in rural areas, accounting for about 36% of the total population. Although this represents a decrease of over 160 million people compared to 2010, it remains a substantial segment of the population.

The aforementioned Chinese political academic also argued that the risk of social conflicts might be exacerbated if overall rural development remains weak in areas with large rural populations.

Using the example of migrant workers returning to their hometowns, he pointed out that another aspect of rural revitalisation is the development of towns and villages. When urban factories can no longer absorb large numbers of migrant workers, these individuals should still be able to find a livelihood back in their rural hometowns.

“If they have nothing to fall back on and nothing to do, what will happen? They might cause trouble and instability,” he said.

The first would be to increase village collectives’ autonomy over the use of construction land — land designated for urban and rural development, including infrastructure, housing and industrial sites — to promote the development of rural industries... — Professor Tong Zhihui, School of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, Renmin University

China’s 2035 vision: success or spin?

As for whether the substantial investment attraction involved in rural revitalisation could become a breeding ground for corruption, the academic assessed that corruption is “inevitable” given the resources and allocation involved. However, he emphasised that rural development should not be abandoned due to potential corruption, and that “the key lies in supervision and prevention”.

Tong Zhihui, a professor at Renmin University of China’s School of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, identified two areas for improvement in rural development. The first would be to increase village collectives’ autonomy over the use of construction land — land designated for urban and rural development, including infrastructure, housing and industrial sites — to promote the development of rural industries, while the second involves creating an endogenous mechanism for local talent — they are made to feel that it is worthwhile for them to stay in the village, thus stemming the outflow of talent.

He thinks that while sending cadres from the provincial level to villages can fill the talent gap, it is only a “short-term, last-resort measure”.

Meanwhile, John Donaldson, an associate professor at Singapore Management University’s School of Social Sciences, pointed out that while China will face “an increasingly hostile international environment” in its push towards achieving modernisation by 2035, “the party will certainly declare that campaign (and the modernisation drive itself) as a success” by that time. The fundamental question is whether the livelihoods of both urban and rural residents will have genuinely improved.

China’s model difficult to replicate overseas

China mobilised its top-down, whole-of-nation system — which spans various sectors of the government and society, from central ministries, state-owned enterprises, eastern cities, and universities — to directly support impoverished regions. Having declared victory in its domestic poverty eradication campaign, China now seeks to promote this model to the global south, positioning it as evidence of the “global significance of China’s poverty alleviation”.

“Once something becomes a political responsibility, the next level down must take ownership. Global south countries likely lack this kind of authority and wouldn’t be able to replicate it.” — a political academic

As Liu Gaiqing, deputy county magistrate of Malipo and a representative dispatched by the foreign ministry to assist with poverty alleviation efforts, provided a vivid description at a media briefing: “It’s because we’ve been rained on before that we want to hold an umbrella for others.”

Responding to African reporters at her visit to Malipo and Jinping, Vice Foreign Minister Hua Chunying said, “Many countries are interested in China’s poverty alleviation experience. On the road to poverty alleviation, no one should be left behind.”

The aforementioned Chinese political academic who wishes to stay anonymous noted that China possesses a strong, authoritarian central government capable of mobilising numerous support channels from the top down. “Once something becomes a political responsibility, the next level down must take ownership. Global south countries likely lack this kind of authority and wouldn’t be able to replicate it,” he said.

During the media trip to Malipo and Jinping, the Beijing-based foreign media delegation frequently crossed paths with African media groups on short-term exchange programmes in China.

When I asked an African reporter whether China’s poverty alleviation approach could be applied in Africa, she responded that poverty eradication requires a “strong and proactive government”, noting the Chinese government’s ability to mobilise significant resources — with even private enterprises participating — to support farmers. “This is rare in Africa,” she said. “Where would the money come from?”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “榴梿飘香驱散昔日硝烟 云南两县走向乡村振兴”.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)