[Video] ThinkChina Forum 2025: China’s future and navigating a changing world order

At the inaugural ThinkChina Forum on 28 March 2025, Professor Wang Gungwu, University Professor, National University of Singapore, joined Professor Yasheng Huang, Professor of Global Economics and Management, MIT Sloan School of Management, in a panel discussion themed “China’s Future: Navigating a Changing World Order”. Moderated by ThinkChina editor Chow Yian Ping, the discussion covered topics such as China-US rivalry, Trump 2.0 and China’s development. Associate Professor Ngeow Chow Bing from the University of Malaya also offered his thoughts from the satellite event in KL. The following is an edited transcript of the panel discussion and Q&A session.

Chow Yian Ping (Chow): Good afternoon SM Teo. Hello everyone! Welcome to the inaugural ThinkChina Forum. I am Yian Ping, the editor of ThinkChina. I am really happy to see many familiar faces among you and just as excited to meet many new friends. Today I have with me on stage two eminent scholars. Our own Professor Wang Gungwu and, from the United States, we have Professor Yasheng Huang. Many of you are familiar with their works, which are like the great symphonies of Western classical music, but please allow me to introduce my panellists.

Professor Wang Gungwu has held the title of University Professor at the National University of Singapore since 2007 and has been an emeritus professor at the Australia National University since 1988. He’s best known for his explorations of Chinese history in the long view and for his writings on the Chinese diaspora. Professor Wang was awarded the Tang Prize in Sinology in 2020. He has just published the book Living with Civilisations: Reflections on Southeast Asia’s Local and National Cultures and will soon be publishing another book on Chinese civilisation.

Professor Yasheng Huang is a professor of global economics and management at the MIT Sloan School and holds the Epoch Foundation professorship of global economics and management. He launched MIT’s first course on ASEAN, with around 50 students currently working with companies in the region on business and managerial challenges. His book, The Rise and Fall of the EAST: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success, and Why They Might Lead to its Decline, was a 2023 Best Book of the Year by Foreign Affairs magazine. He’s collaborating with other scholars on book projects about Chinese historical inventions and the Chinese economy.

Over in Kuala Lumpur, we have one of ThinkChina’s long-time contributors: Associate Professor Ngeow Chow Bing. That’s Dr Ngeow there. Dr Ngeow is Associate Professor and Director of the Institute of China Studies at the University of Malaya and a non-resident scholar at Carnegie China. He’s the editor of the book Researching China in Southeast Asia and the co-editor of Populism, Nationalism and South China Sea Dispute and Southeast Asia in China: A Contest in Mutual Socialisation. He has published in various academic journals as well as media and policy-oriented online platforms. Thank you, Prof Ngeow, for joining us from Kuala Lumpur.

Well, this is an uncertain, unpredictable and difficult time for many people around the world, and we are here to find answers or to better understand our situation. We shall start with the panel presentation, and after which I shall open the floor for questions and answers.

Determining factors to lead in the new world

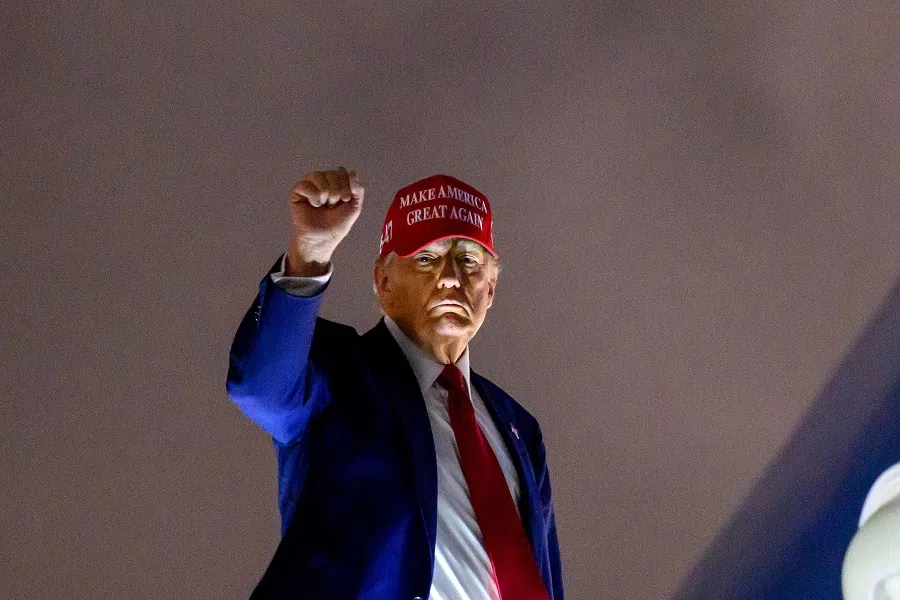

My first question for our panel is as follows: on one side of the globe, the Trump administration aims to make America great again. On the other, President Xi envisions the rise of the East against the decline of the West. Both face their own governance and foreign relations challenges. In this era of disruption and unpredictability, which country holds the greater chance and ability to lead the future world order? May I invite Professor Wang to speak?

Wang Gungwu (Wang): Thank you Yian Ping. You’ve asked a very difficult question, I have to say. A changing world order, China’s future — both extremely challenging issues. But let me take advantage of the fact that China is a country deeply concerned for its own past. Therefore, look at its past as a starting point. Because I think we can say that China had a world order of its own. But its world was not the same world that we look at today. It was a world which was primarily centred on the Eurasian continent, of which China, it saw itself as the centre of the civilised world.

And they had developed ways and means of handling the world order throughout that time. And they were very confident. They had times when they rose and times when they fell, and they will rise again and again. And each time they came out of it, as it were, stronger.

China’s world

And it was related to Central Asia. Because all their enemies and people who could threaten China came from the continent. And it looked upon the sea as somewhere safe and useful for trade, but not really a threat to China — ever. And that’s how it developed itself for at least 3,000 years. And that view of a world order, in which its security, its safety, and the harmony, and social growth and cultural evolution over the centuries developed in that framework, that world order.

And they had developed ways and means of handling the world order throughout that time. And they were very confident. They had times when they rose and times when they fell, and they will rise again and again. And each time they came out of it, as it were, stronger. And this is the heritage that the Chinese have. And I think this background is extremely important. Because this is what China believes that it can do. Because it has thousands of years of that kind of experience.

That world order, however, that they took for granted for so long was challenged about 500 years ago. But they didn’t really pay much attention to it. And roughly about 1500 thereabouts, the world began to change. The Chinese were aware of it because they saw what was happening in their neighbourhood, and both on land as well as at sea, but they were so confident in their own system that they did not feel that that was a threat to them. So the world order — in their minds — did not change. But, the world order was actually changing outside of China. And that world order was changed by circumstances which the Chinese didn’t fully understand.

From land to sea

And that, I would say the most important part of that challenge was the fact that the countries of Western Europe found themselves blocked from great civilisations like India and China — they were blocked by the Islamic world. The Ottoman Caliphate and all the Islamic countries across North Africa to Iran into Central Asia basically monopolised all the trading and economic relations between them and India and China. And Western Europe and the western part of the Mediterranean could not reach them; they were blocked altogether.

Forced by those circumstances, they looked to the sea. And they had that experience from being a Mediterranean civilisation. They looked to the sea, and the Portuguese and the Spanish turned to the ocean, recognising — and that’s something new — that the world was round — at least they thought it was round. And they did that. And that actually was the beginning of a major change to the world order.

And I believe that that fact — that they went round — created a global world order which had never existed before: A global world order based on naval power. And they began, of course, in the early days they were just fighting the Islamic competitors in the Indian Ocean, and they went round the Cape of Good Hope, and went round the South America into the Pacific Ocean. But as they advanced, they developed at the same time, inspired Western Europe itself to change.

So when the Europeans evolved from there, into scientific new knowledge, derived a lot of inspiration from… what they learnt from — at that time — a very highly developed China, technology and governance; and at the same time scientific discoveries from the new continents of North and South America, inspired a scientific tradition where it really transformed the world.

That scientific tradition was the basis on which a new world order could be created. It meant that trade, to the use of superior naval power, became the determining factor in that world order. And, of course, without anyone quite realising it, that naval power grew and grew and grew for about 300 years. By the 19th century, it was really superior.

And it was a basis of a new set of political circumstances that grew out of Europe: Tthe idea of a national state. A nation state, which then controlled the empires that had been built by these naval forces that went into the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. And with that, the national empires that were built became the basis for the new global order dominated by whoever could control the naval forces of the world.

And as we know, for about a century or more, the British Navy was the most efficient and technologically advanced of all the merchant navies and naval forces of the world, and they dominated. The French tried to compete, but they basically didn’t. But for various reasons, they decided to share the world between them, and as a global order, world order, dominated by two naval powers, the British and the French. And that remained so for the whole of the 19th century.

From rivalries and wars to co-existence

But what it did was it created a world in which great power nationalism and national imperialism based on industrial capitalism became the basis of this world order. And with that, it basically dominated. It determined the whole structure of the global world order for the next 200 years. And what it really proved was that maritime power was superior to continental power, which had been the basis of an earlier world order — which was never really global; it was only limited to the Eurasian continent — but this was global.

And that global power has enabled the British and the French to dominate for more than 100 years, but it was challenged. Because the moment you do that, and you’re basing yourself on national interest, other nations also wanted to have a share. And so the rise of Russia, the rise of Germany, Italy, and all the others as they industrialised by copying the British industrial revolution, they began to challenge it.

So the result of that international world order was to create two world wars that basically destroyed that system. And out of that system, the Americans would help the Anglo-French forces defeat the enemies and the challengers of that world order, then became the masters of that world order. And out of their idealism, and their idealism about democracy, and all the matters which are derived from their own history, their own constitution, they created the United Nations, which was supposed to be superior to any other system in the past. And that global international world order has been what we’ve been living with.

And I think we all recognise that for those smaller countries, like those in Asia, which had never been nation states before, the idea that they will be in a world in which all nation states will be equal, sovereign, and all members of a United Nations, determined to bring peace and prosperity to the world was wonderful. And it was a world order which I think most people accepted.

When Trump says “Make America Great Again”, is it so that they can reestablish a unipolar position to dominate the world? Or are they retreating from that position, maybe into a isolationist world at the other extreme?

Unipolar US and its future

But in fact, of course, from the very beginning, it wasn’t quite a world order. It was in a way a bipolar world order which, from the beginning, we had the Cold War and rivalries on ideological grounds. They fought each other, but except that they fought each other through their vassal states and others, and never directly fought each other because it was too dangerous. It was a nuclear threat to the world. But that survived for 40 years. But nobody expected that war, that civil war, that Cold War to end so suddenly by the 1990s. And as a result of which, that world order was itself changed from a bipolar system into a unipolar system.

That created a new perspective for the United States, I’m not sure that they expected to have suddenly, but when they achieved it, it led to, in a way a misreading of history, that they could actually be a unipolar system in which they would be able to tell the world how to be a better world. And they were idealistic about it. They did try their best — from their perspective — to make the world better. An international world order which they would help.

But as we all know, after 30 years, that unipolar world order has been seriously challenged. And today we look at United States today — we’re not sure where they’re going to go.

When Trump says “Make America Great Again”, is it so that they can reestablish a unipolar position to dominate the world? Or are they retreating from that position, maybe into a isolationist world at the other extreme? I, for one, don’t really know what is going to happen. But what I do understand is that these choices are now facing China.

Because one thing the Chinese have learnt, which they never learnt before, is that there is such a thing as progress. Because in the past, the Chinese always looked to the past as a model for them to follow.

Not just the past, but also the future

And so we come back to China, now to China’s future. China is looking at this world that is changing around them, while in the meantime, for them, what they had been doing after the 19th century is to survive. Because they were challenged at the end of the 19th century, their civilisation was threatened. China almost had disappeared. It could have been broken up into many many different countries. And they were attacked by Japan, and they had a civil war, and the PRC was founded under conditions which were unexpected at the time. But they have succeeded.

What they have succeeded, is not that they have done that much, but they succeeded by creating a unitary China, with central power, with a party state, reinvented to perform all the conditions of a powerful centralised, bureaucratic state. And despite Mao Zedong’s extreme illusionary dreams about what to do, a China that would be reestablishing its own world order didn’t work out. As we all know, it failed, essentially because economically, they couldn’t do it. A political world order by itself, without economic power, is failure. So now they have really relearnt it.

And what they have done is that they’ve achieved, to everyone’s surprise, in a matter of a few decades, a position which has made it to be the second most powerful economic country in the world. So they now have to face this future. As Senior Minister has already outlined, all the things that they face today is very challenging. But the crucial part is that… how do they see their future?

Because one thing the Chinese have learnt, which they never learnt before, is that there is such a thing as progress. Because in the past, the Chinese always looked to the past as a model for them to follow. But now they believe in progress. They have themselves achieved progress at such a rapid pace that no one expected, and they now are looked to as a possible model for future development. Now they are in a very different position.

Because China represents still a connection with continental power of Eurasia, which the United States cannot control. But the United States controls the maritime power to a point which the Chinese can never really challenge. So this is a tremendous challenge.

The China threat in a new world

And from the point of view of a unipolar system that the Americans have inherited, they see that as a definite threat. I mean, China doesn’t mean to be a threat to the United States. It just wants to become itself — secure and rich and powerful — but the United States will say that anything that would threaten its hegemony, its particular dominance, would be a threat to their interest, is perfectly understandable.

But from that point of view, this has led to the kind of challenging world order that we are facing today. And what we don’t know, and China’s future does depend on it, is where do they… what is their [America’s] stand on this world order? It’s because they don’t know exactly where America’s going to go, because China also wants to be great again — it’s not only America. And being great again means, now, in a different context; it’s not being great again in the days of when it was a small world order on the continent. It’s now a global world order which has both continental and maritime power.

Because China represents still a connection with continental power of Eurasia, which the United States cannot control. But the United States controls the maritime power to a point which the Chinese can never really challenge. So this is a tremendous challenge. A tension which I think cannot be avoided. And the Chinese have to find the right balance.

So I would end simply by saying: China now has to think back to its own priorities. And my understanding of the Chinese is something again that the Senior Minister referred to, and that is that China has a long view.

The rise and fall of China

It doesn’t believe that it’s something that they achieve in five years or ten years would make that much of a difference. What really counts is to be able to achieve your own goal that is reliable, stable, sustainable for a long period of time. And in order to do that, to have the patience to do it over time, and not to rush into something and make bad mistakes. That is their tradition and heritage. And they have proven in the past, that by following that method, they have actually gained. Every time they had a struggle, they actually gained. Coming out of a period when they fell, when they rose again, they were more powerful and more secure. This is their tradition that they believe in. And I believe that this part of their history is very much in their mind.

They’re trying to adapt it — the idea of a future in which they will make progress. They will become more and more powerful, more and more economically developing, and becoming rich again, so that they can get genuinely secure and safe from the enemies. But the enemies now are not just continental enemies, but enemies can also come by sea. So they have to do that to be equally powerful, to secure your maritime interests. So that, of course, is a major challenge for the maritime powers, like the United States and its allies.

I can imagine people who would think in terms of continued hegemony, would be possible to be established using the same Cold War methods to create a NATO plus IPTO to make sure that China could never develop and would always be kept down, if not ultimately destroyed and transformed into something that is acceptable to the United States.

NATO plus IPTO?

I would simply end on one thing. If I’m not mistaken, it is still possible for Trump and his team to go back to the position of being bipolar. In other words, they don’t accept a world in which there’s no multipolarity, that China might prefer. But they would like to go back to a bipolar system in which their superiority at sea could completely dominate the ocean, and that would actually limit the possibility of Chinese economic development because the sea’s so important for economic development.

And in so doing, their previous success provides them with that inspiration, that is, that they had a North Atlantic organisation that succeeded in destroying the Soviet Union. And they could create an equivalent body on the other side. They could probably do the same to China, so it’s a kind of NATO plus, if we have the phrase, I would say call it IPTO — the Indo-Pacific Treaty Organization on the other side.

And between the two, and I can imagine people who would think in terms of continued hegemony, would be possible to be established using the same Cold War methods to create a NATO plus IPTO to make sure that China could never develop and would always be kept down, if not ultimately destroyed and transformed into something that is acceptable to the United States. I would end on that note. And China is fully aware of that possibility. How it responds? I do not know. But I think it must be very very careful how they do handle that.

Chow: Alright, thank you Prof Wang for that very insightful and forthright sharing about the historical foundation leading to the current situation and the choices facing both countries. Can I now invite Prof Huang to speak, please?

Yasheng Huang (Huang): Thank you very much, Yian Ping, and I look forward to conversations and discussions with policymakers, business leaders and academics in Singapore in an environment of honesty, direct style and free exchange. So, on your question about the East and the West, I think we need to make a distinction between the East and the West as a geographic concept, and the East and the West as a conceptual, intellectual concept.

China before 1978 had some economic progress, but all the gains of Chinese economy that had been created, 99.9% of that is happening after 1978, as China was moving towards a market economy and globalisation.

Different systems, different lives

As a geographic concept, the rise of the East has already taken place since the Second World War. Today we focus on China, but let’s not forget that since the end of the Second World War, the countries and the economies that were growing the fastest were mostly in East Asia: South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore — Singapore is Southeast Asia, but if I can be a little bit loose on geography — and Hong Kong. The four tigers plus the big Japan.

In 1978, if you look at the world economic map between 1945 and 1978, the rise of that part of the East was already changing the economic balance of the world. Except for two countries: China and North Korea. In 1978. North Korea is still mired in poverty, and, in fact, if you go back to the early 1950s, North Korea was the richer of the two Koreas. And today, the average height of North Koreans is shorter than the average height of South Koreans. And the difference is that arbitrary border between North Korea and South Korea, drawn out by two American colonels, totally arbitrarily — they just drew the line 38th parallel. But that line determined the fate of the people living to the south and people living to the north of that 38th parallel.

Clearly, it’s not geography, it’s not genetics, it’s not culture, it’s not the food that the South Koreans ate that made that difference — it was the economic system. South Korean system embraced globalisation, embraced parts of the market economy. They had autocracy, but it was a more open autocracy as compared with the totalitarianism of North Korea.

China before 1978 had some economic progress, but all the gains of Chinese economy that had been created, 99.9% of that is happening after 1978, as China was moving towards a market economy and globalisation. We can debate about the nuances and the complexities of the role of the government and the role of the market, the role of the private sector, the role of the state sector, but let’s just keep the big picture in our mind.

China had all that power of the government before 1978. China had, you know, whatever form of the government you want to describe it. China had the power of the state. China even had science and technology in certain areas. But the economy didn’t grow until the country began to embrace market economy principles. So this kind of debate about the role of the government and the role of the market economy, sometimes, it’s a little bit about the debate of the trees, rather than the debate of the forest.

But Soviet achievements in science and technology were not combined with entrepreneurship, were not combined with a profit orientation, were not combined with the market economy. And in the end, it didn’t deliver.

Technology, markets and growth

If we look at history, and there’s a website called Our World in Data, if you pull out the GDP of the humankind all the way to year zero, it basically remained a flat line. Some people argue, oh, China was number one in terms of GDP in the Qing dynasty. I believe even the most ardent nationalist in China today will not argue for China to go back to the Qing dynasty, when China actually had the biggest share of the world GDP. But that was purely because of the population.

Before technology, the labour productivity of the world, of different continents, of different nation states, was basically identical. There could be some differences, maybe by 10%, by 20%, but without technology, one person cannot be 100 times more efficient and productive than the other person without technology. The rise of the technology, the scientific revolution in the 17th century, 18th century, then you look at that timeline: The GDP shot up. Medicine began to develop. Technology began to develop. Travel, cars, automobiles, chemistry, physics. It happened after the scientific revolution.

It happened after the scientific revolution, industrial revolution, actually not because of science and technology per se, for China at one point in time was the most developed country in terms of science and technology, according to the massive work done by Professor Joseph Needham. And we’re continuing that work, except that we’re doing it statistically because we have established a database on Chinese inventions in history.

The combination of scientific progress and market economy, rule of law, independent academia in England — that combination was the reason why the GDP began to grow dramatically. Soviet Union had scientific progress. Soviet Union has some very impressive technological achievements. If people are interested in this topic, there’s a book by the name of Lonely Ideas. But Soviet achievements in science and technology were not combined with entrepreneurship, were not combined with a profit orientation, were not combined with the market economy. And in the end, it didn’t deliver.

If you look at the EV battery industry in China, a lot of it happened due to collaborations with Western, Japanese companies, Western, Japanese scientists.

The importance of institutions and global collaborations

So this is a long way of saying that we really need to keep our perspective right when we think about policy choices that countries are contemplating. No, I’m not saying that we should go all the way to laissez-faire and forget about the government and I think that’s totally wrong. But on the other hand, if we fail to acknowledge the important contributions of basic market economic principles, if we fail to recognise that the importance of institutions in stabilising the incentives, in encouraging incentives, if we fail to recognise the important role private sector and entrepreneurship have played historically in Chinese and the world economic development, if we fail to appreciate those contributions, we are bound to make wrong policy choices. And this is, I believe, not unique to China.

I think the United States is making that mistake, and by negating free trade, negating the role of globalisation, and that I think it’s incumbent on other countries, as the United States goes in that direction, it is incumbent on other countries to continue on this path of collaborations — Senior Minister was talking about cooperation, and I would use that term as well — cooperation, collaboration.

If you look at the scientific, technological achievements that China has made, many of them have been made on the basis of collaboration and cooperation. Look at Huawei. If you have a Huawei phone, look at the side of the Huawei phone that has its camera lens. You’re going to see the name of Leica there — German optical company. Before 2018, Huawei collaborated with over 120 American companies. When I visited Huawei a few years back, the person who hosted me was a British national. He was the chief strategist for Huawei company.

And DeepSeek benefited from OpenAI’s foundation model. They’re extremely good, they’re extremely clever in terms of optimisation, but the foundation model is on the basis of… their model is on the basis of the foundation model pioneered by OpenAI. Tesla made its software algorithm open source. Chinese companies have also benefited from that open source. If you look at the EV battery industry in China, a lot of it happened due to collaborations with Western, Japanese companies, Western, Japanese scientists. Right? So, this is the intellectual part of the discussion.

Rise of the East in a more open world

Are we really seeing an era where the rise of countries such as China and, I would also argue, Singapore — we can come back to this topic — really fundamentally defies some of the basic principles that we know about how economic growth has happened? There are nuances, there are complexities, and I would be very happy to discuss those, but in my own opinion, the rise of the East has taken place under an environment, under a institutional context where the countries are beginning or are moving towards a more open world — both politically and economically and, to some extent, intellectually — globalisation, to be part of the global economy, to be part of the collaborative ecosystem between the East and the West.

China has its own huge advantages — the ability to scale the human capital — you have mentioned that now 11 million Chinese are graduating from colleges, about 50% of them studied science and mathematics. Right? US, it’s about 17%. And each year… I cannot guarantee that this number is correct, but maybe 2 million, 3 million. So 17% out of the 2 million or 3 million vis-à-vis 50% out of the 10 million. So China has that incredible advantage, to be sure, in terms of the numbers, in terms of the scale. But if we fail to recognise that capability is only going to deliver — in terms of economic growth, in terms of improving people’s lives — in an environment of market economy and collaboration; if we fail to recognise that, we’re going to make some mistakes.

Derailing China’s development path

Chow: Alright, thank you, Prof Huang, for that thoughtful sharing and the discussion about the importance of institutions and continued collaborations, which is important for the development of both countries.

I would like to discuss China further. What factors do you think would derail China’s current development trajectory? Will the removal of term limits create a succession issue? Would the Taiwan Strait become a flashpoint with the potential for conflict? May I invite Professor Huang to speak?

Huang: These are difficult questions. I think… if we put Trump aside, as much as we can, if we put that aside, I think what can derail Chinese economic development, and I can say this, historically speaking, most of the factors that had impeded Chinese economic development were created within China: Central planning system, Cultural Revolution, the Great Leap Forward. These were not decisions forced by other countries on the country.

And economic research has long shown that if the Chinese government reformed the hukou system, that can raise the domestic consumption anywhere between 8 to 15% of the GDP.

Tariffs, war and recession

For a country the size of China — the continental size economy, 1.3 billion, 1.4 billion in population, now the second largest GDP in the world — China actually has unique capacity to insulate itself from the volatility of the global economy. And I believe that China needs to do more of that now, in the age of Trump 2.0, with a tariff war, and since… for the last two months, the recession fear has arisen.

I’m not going to say it’s a consensus estimate, but now the concern is that within this year, the recession can be… the probability of recession is something like 50%. Biden economy was actually very strong, just across the board. So, this is a purely policy-induced recession. And China, and large countries like China… Singapore because it’s a trading economy, it will be affected fairly directly.

But for countries like China, India, Brazil… the sizeable economies, they have a huge advantage, which is their domestic market, domestic market potentials. But for China, specifically, to unlock those potentials, the country needs to do more in terms of growing the income of its people. The rural Chinese especially, in terms of their pension levels and land rights, hukou reforms.

And recently, a number of established economists in China are calling for raising the pension levels for the rural Chinese. And economic research has long shown that if the Chinese government reformed the hukou system, that can raise the domestic consumption anywhere between 8 to 15% of the GDP. Essentially, China will not need to export so much if China unlocks this incredible potential of its own market. And I really support that view, and I have advocated that view as early as 2008. And in 2008, I published the book calling for reforms of the hukou system, the pension system. I think that’s the best secret sauce — it’s not that secret — best instrument that China can have to protect itself against the possibility of global recession.

China will not be the next Japan

So it’s very important that when we talk about China being the second largest GDP, that’s aggregate GDP, it’s not per capita. Per capita GDP, China still has a long way to go. If you look at Japan, [China] is very different from the Japanese situation in the early 1990s, when the Japanese per capita GDP was either at the same level or even a little bit off the US per capita GDP. And then Japanese economy began to stall.

Chinese per capita GDP is long way from the US per capita GDP, so China has a lot of room to grow. And China has other advantages that Japan didn’t have, such as entrepreneurship; such as a combination of science and technology with business development; venture capital industry, globalisation, a very outward-looking mentality. So there’s high debt? Sure. Real estate problem? Sure. Ageing population? Sure. But also China has other assets against these similar liabilities. There’s no reason China has to repeat the Japan story if China is going to reform some of these features of its economic system.

Chow: Thank you, Prof Huang. Prof Wang?

Wang: This is a very difficult one, and I share Professor Huang’s concern about the economic future for a system that is basically so centralised and so highly dependent on a handful of people to make vital decisions, policy decisions that could affect everybody. There are certain dangers, fundamental dangers, when the decision making is in the hands of so few people.

The traditional method that the Chinese have always had successfully dealt with such problems is to keep everything local. In other words, if there are protests, dissatisfaction, unhappiness, if they can be kept local, they can usually handle it.

Rising expectations of Chinese society

And of course, in particular, those few people who are not necessarily capable of handling issues of economic development. They are more politically motivated. And therefore that gap between the political wisdom and economic wisdom can be too great for them to make a difference, to make the country, to ensure the country continues to thrive. So the dangers are there.

But the thing that troubles me most, anyway, is that expectations are high. We had mentioned that before, that modernity, modernisation has improved people’s prospects to a point when the expectations continue to grow, and if your system fails to meet that growth, you will find objections rising among more and more people. And the young people who have those expectations will feel more frustrated if they don’t have their expectations met. That is one general thing.

The traditional method that the Chinese have always had successfully dealt with such problems is to keep everything local. In other words, if there are protests, dissatisfaction, unhappiness, if they can be kept local, they can usually handle it. They can send somebody there — party leader — send there to make concessions and so on. Local problem. The issue is to never allow anything to cross borders into other counties, into provinces, into something that is national. If they can avoid that, then the stability of the country as a whole is probably quite well assured.

The one area which they have always had difficulty with is, it’s actually with the intellectual classes, with the educated people...

How China maintains stability

So when Professor Huang says that the internal problems are usually the problems that undermine authority in China, that is perfectly true. And it’s exactly when the central government fails to prevent something from being just local and allows it to spread into national concerns. And the Chinese Communist Party, from the very beginning, recognised, and even traditional China, recognised who are the potential people who are likely to cross borders, to become difficult.

On the whole, people of peasant background, no such problems. They can be hidden, easy to localise. The working class in China has also been more or less put in that position because of the way the country controls all the trade unions that the workers belong to. The military… which is usually the most dangerous part in Chinese history, has also been, to some extent, controlled by the fact that all the leaders are members of the Chinese Communist Party and are controlled by the discipline of the Chinese Communist Party. So they have actually carefully measured out the areas where local dissent can always be managed; broad national dissent can be controlled and not allowed to spread.

The one area which they have always had difficulty with is, it’s actually with the intellectual classes, with the educated people, the people who have access to outside knowledge, who can bring knowledge from outside, make comparisons with the outside world, and create dissatisfactions. And as you can see, the party state is so particularly sensitive about what is taught in universities, in schools — the control of textbooks and so on. It’s because this is the one area that could be nationally effective.

Because if all the young students of China read everything available to them from the outside world, they can share something which is nationwide and cannot be localised, they actually have the capacity to raise an issue which is accepted nationwide — the whole country can respond to it; all the intellectuals can respond to it. And this is where I think the Chinese are extremely sensitive to. In the one area which I think they will never be taking their eyes off. This is the one area they’ll be particularly careful about. So as long as they can control that area, they can prevent anything serious from happening. All the others are manageable.

I know there are areas where people say, with the PLA, you can never tell. After all, they do hold the guns. But I do believe that the great strengths of the Chinese Communist Party since Deng Xiaoping’s reforms — we always emphasise his economic reforms; we tend to neglect his political reforms. His political reforms is primarily to make sure that the Chinese Communist Party will always be in charge. And you can see that from Tiananmen onwards, that the Chinese Communist Party is China. Protecting and saving the Communist Party is saving China. It’s the most patriotic thing you can do. And if you devote your attention to make sure that discipline within the Communist Party is highly sustained, then your chances of controlling the PLA are pretty good. And this is, I think, what they are counting on. And I think they still have a very good chance of doing that. So I do not think that it’s a serious one.

And if I’m right in believing that all Chinese feel much more comfortable taking the long view than a short-term view, then I think both sides can live with this indefinitely.

A war over Taiwan?

I know that Professor Huang has not talked about your second question, and I also understand why it’s a sensitive one. I would also find it very sensitive. But I think it is important to face up to it, that Taiwan is an issue. And that issue is a very traditional issue, to my mind. It is the issue that China must always be one. Tian wu er ri (天无二日) is the traditional idea — there’s only one sun in the sky, and it must always be one.

A united China must be uniting all of China. And Taiwan is part of China. That was how it inherited the whole thing. And it includes, incidentally, 11 dotted lines that nationalist China had adorned, which PRC inherited, that it become the inheritance that of 1949. They inherited everything from the Republic of China. And therefore that includes Taiwan. And therefore Taiwan is just a province of China. Now this is so, you must say, sanctified in the tradition, in the whole, you can say the whole historical development of China, that ultimately, unless it is one, it is never quite secure. And it has always been that. So I think that will remain, and therefore it is a red line which they will not allow the Taiwanese to cross, to declare independence.

But as we know, it is entirely possible for the Taiwanese government never to declare independence. They have again and again said they don’t have to. They are the Republic of China, which has been in existence since 1912. It just happened to occupy a smaller area. But its legitimacy, and the fact that it exists, is indisputable. It was after all a member of the United Nations as a security council, one of the five security powers for over 20 years, as the Republic of China. So why does it need to declare independence? So as long as it doesn’t declare independence, at least in terms of what the Chinese themselves have said, they will not invade Chinese… they will not attack Taiwan. They will try to resolve the problem peacefully.

And if I’m right in believing that all Chinese feel much more comfortable taking the long view than a short-term view, then I think both sides can live with this indefinitely. Because in the long view, they will say, “It will resolve itself. It will happen. But we don’t act just to try and solve a problem immediately, like other countries try to do, and create more trouble and actually endanger the whole situation itself.”

So it is in that context I feel confident that the Chinese would not attack Taiwan unless they declare independence. The Taiwanese are intelligent enough not to declare independence. And unless somebody provokes it deliberately, to want to start something, there will not be a war over Taiwan.

Chow: Thank you Professor Wang. Can we turn our attention to Kuala Lumpur, please? Can I invite our panel respondent, Prof Ngeow, to share his views?

Ngeow Chow Bing (Ngeow): Thank you very much, Yian Ping over in Singapore, and I’m very glad to see also esteemed panellists over there. I’m given the honour to respond to the remarks made by two esteemed speakers. But I also want to actually stress that the opening speech presented by Senior Minister Teo was also a very penetrating, very deeply insightful speech. So I think all the speeches are very very helpful.

But of course Prof Wang and Prof Huang, they all… both have given us a very broad, very deep overview of many many aspects of the issues that we have touched upon, and it’s actually quite difficult to digest immediately and then come up with a very systematic response, but I will try to do my best, and I will try to highlight certain key points that we can get.

... the policies that the Trump administration is pursuing may actually be counterproductive. And in that case, you could see actually the stagnation or if not the decline of the two largest economies both at the same time.

Are both China and US losing momentum?

Basically, I would first start with some of the things that Prof Huang mentioned. I actually kind of developed this first by relying on the book, the latest book, The Rise and Fall of the EAST. And of course I understand that he’s still working on this, on the project based on the ideas of the book. Basically the argument is the post society, homogenising society, a society with less intellectual openness, collaboration, which I think Prof Huang mentioned a couple of times, in the long run, if not in the short run, generally we will make the society decline. Has a detrimental effect.

Even if it comes with certain scientific progress, certain technological progress, but eventually it will result in the very long-term decline of any society. And in that sense, I think the assessment is that this is not a very good era for China, and in that case, also for the United States, because openness is shrinking, collaboration is shrinking, and then they are reducing the chances for both societies to grow together, to learn from each other. And in the long term it will have detrimental effects for both sides.

But when it comes to China, Prof Huang also mentioned that China is a continental-sized economy; it can do a lot of things on its own, even if it is facing challenges abroad. But you should be able to overcome certain things. He particularly mentioned, how to unleash the tremendous energy and potential creativity that exist in the Chinese society. So China still have tremendous to offer, but how to actually give the Chinese authorities to have the full confidence to unleash this energy? That is a different matter.

The economic challenges that the Chinese government, or the whole of China faces today of course is quite serious. I don’t think the leadership of China is in any way underestimating the challenges that it’s facing, but the corrective steps that the government has taken so far is still not yet a fundamental approach. It’s not yet a fundamental solution to the problem of how to actually unleash the private sector, the energy of the people.

So if that is the case, of course China will still be there, will still be powerful, will still be a very major, important economy and country, and will still make progress, but it wouldn’t be fully realising its own potential. And the more pessimistic view will be probably, it will actually enter a kind of a long-term stagnating stage, if not decline.

On the other hand, the United States, even though there is a president who wants to make America great again, the policies that the Trump administration is pursuing may actually be counterproductive. And in that case, you could see actually the stagnation or if not the decline of the two largest economies both at the same time.

Of course, this is just one possible scenario, but it is one of the scenarios probably we in Southeast Asia will have to bear and cope with. Because we have tremendous, important and dynamic economic relationships with both China and the United States, and if both of them are entering periods of decline or stagnation or uncertainties and so on and so forth, well that will also be bad news for us in Southeast Asia.

... I think Prof Wang and Prof Huang actually have quite similar diagnostic and prescriptions. China needs a more robust, more vibrant citizenship, private sector economy.

Both professors offer similar prescriptions for China

And Professor Wang, of course, comes from a very deep historical insight, all the way from hundreds of years, if not thousands of years, all the way until today. I think his long-term observation of the long history of China, he mentioned something about, transitioning from continental power to now contesting in the maritime domain, and how the choices that China has to make, will be something that in a way determines the regional stability and also in the future. And in a sense, the choices is about how to also manage and govern a gigantic complex country and try to also strike a balance.

Professor Wang also mentioned how to actually kind of have a very balanced approach about dealing with a centralised power and a dynamic private sector. How to ensure some form of a cohesion and unity, as the responsibility of the government, but also not to the extent of stifling the creativity and imagination of the people. It’s very difficult to get this balance right all the time or even most of the time. And most of the time, probably it’s not the case. More often than not, it’s that the decision makers tend to overdo things in trying to solve one previous problem, they actually create other problems and other new situations.

And in that sense, I think Prof Wang and Prof Huang actually have quite similar diagnostic and prescriptions. China needs a more robust, more vibrant citizenship, private sector economy. The government is very important, is very vital, to play a role to stabilise the whole country, to govern the whole country, but it needs to have some kind of a self-discipline in stepping away from certain things that should be in the private sector, there should not be too much involved from top down, to generate the kind of wealth that will sustain the progress of the country.

But of course the thing is that in today’s China, there is also the rising expectation that has been mentioned. The Chinese younger generation especially, they have basically lived in the age of continuous modernisation and progress, and they believe that the future should continue that way, if not higher expectation. But how are the authorities actually preparing to be more open about facing these rising expectations? I think this still remains a question mark, and it’s one of the key fundamental choices that the Chinese government will have to make.

Openness is key for China

So if I have to summarise, in one very short gist about what both esteemed panellists mentioned, I think it’s the idea of openness. Of course, China’s government has continued to say that they stay open, and we have to observe whether it is true to its form or not. And I do believe that there is recognition that openness will be beneficial for the country, and there are areas where China is very committed to really truly be more open about it.

But there are, again, as I said, some fundamental sense about whether China is… Chinese government is prepared to be more open than before. So I think I will basically offer these few remarks as my response to the panellists’ speeches. Thank you very much.

Questions and answers session

Chow: Right. Thank you Prof Ngeow for that very concise and precise sharing. Now let me open the floor for questions and answers. Please do three things: Tell us who you are, where you are from, and keep your questions concise and to the point, so that we can hear from as many people as possible. If you have a question, please raise your hand, and we will pass a mic to you. Yes, Prof.

But that idea is that the humankind has figured out two competing ideas about governance, and one is democracy and autocracy; we haven’t figured out that third way. So Trump, I believe, is trying an untested third way.

What Trump is trying to achieve

Q: Hi, I’m Kishore Mahbubani with NUS. I have a question for Professor Yasheng Huang. Welcome to Singapore, Yasheng. You said that we should put Trump aside. Unfortunately, we cannot put Trump aside. He’s emerging as one of the most consequential American presidents ever, shifting the political dynamic in the US and in ways that very few presidents have been able to do so. So if Trump proceeds with two things that he’s doing: One, trying to dismantle the US government. Two, alienate key allies like Canada and Europe. What would be the worst-case scenario you think that could result if he succeeds in these two what I would call “relatively disruptive tendencies”?

Huang: Good to see you, Kishore. I think we can only conjecture, right? Speculate. But I would argue that the United States now is moving into one of the most perilous moments in its history. And this end-of-history idea, which was invented by Hegel, that idea is not that democracy is always going to win. But that idea is that the humankind has figured out two competing ideas about governance, and one is democracy and autocracy; we haven’t figured out that third way. So Trump, I believe, is trying an untested third way.

And the departure that he is creating is from a system of democracy with strong expertise in the government, with the policy consistency across different administrations, embedded in bureaucracy. So lot of the people in America don’t quite understand this point, and the Republicans have very negative things to say about bureaucracy in the United States.

First of all, the federal level of the employment is at its lowest level, historically speaking. So it is the most lean federal government ever, historically speaking. Secondly, we often complain about democracies not able to have a long-term view — administration change, policy changes. I think all these complaints are absolutely legitimate. But if you look at where the policy consistency comes from, it comes from bureaucracy.

Federal Reserve is independent from the Congress, from the White House. Commerce Department has scientists working on agriculture, on weather, on soil conditions, and NIH is an independent organisation granting funds to support science and technology on the basis of scientific merit rather than on the basis of political considerations.

He is demolishing that part of the… one part of the consistency that democracy desperately needs, to maintain policy stability and operational consistency. And he’s also undermining the professionalism of the federal government. I don’t need to bore this audience with the recent episode about conducting war on a commercially available app, Signal, but it’s just unbelievable, right?

Sometimes these shocks that are happening can change the world history. And I’m afraid that the next one may happen.

Undermining US power and strength

And the takedown of the universities now. If we can think about one really really bright spot of the United States, it is its research universities and the ability of the research universities to create science and knowledge that not only benefit the United States, but also benefit the entire world.

There is a study of MIT’s creation of science and technology; its impact on the economy. The estimate is that the MIT effect was equivalent to the 11th largest GDP in 2014. 11th largest GDP in 2014 was South Korea. Stanford then conducted a similar study. They came out with a conclusion they were the equivalent of the tenth largest GDP. So you’re undermining one important source of economic development, entrepreneurship, development and scientific progress.

They’re undermining the FBI. And I worry about the ability of the federal government to keep the country safe. CIA, FBI. And undermining the soft power of the United States, USAID. There are people in Africa who depend on the vaccines and drugs, and funded by the USAID.

I mean, we can talk about the ways and the fraud in the government. I think that’s a very legitimate debate. I also think that it is a legitimate scepticism to examine what the government does, and subject them to scrutiny and transparency, and to modernise the operations of the federal government. But to demolish the federal government as it is, to interfere with the independence of the monetary-making authorities, that’s going to undermine the credibility, the financial credibility of the US government and the ability of the US to borrow from the rest of the world to fund its many operations. It’s going to be undermined.

So I don’t quibble with some of the criticisms that President Trump and Elon Musk have levelled against the federal bureaucracy, but I worry about this particular approach that they have adopted. So the thing about the government, and I think I can say this without being terribly controversial in Singapore: The function of a government, when it works well, is that we don’t notice it. We don’t notice it. The most successful firefighters are the ones that prevent fire.

And when we dismantle the government, we’re going to miss it. But we are going to miss it only after disasters, and that’s not a price that we should be paying. And it is not a price we should be paying especially because the reorganisation of the government, rethinking about the government, are not based on an empirical approach, a careful approach. It is based on this kind of an ideological approach.

So that’s my worst-case scenario. Right? So something really bad happens, and that has global implications. Look at 9/11. 9/11 changed the world history — invasion of the Iraq, which was totally a war of choice, rather than a war of necessity. It was due to 9/11. So we cannot underestimate. Sometimes these shocks that are happening can change the world history. And I’m afraid that the next one may happen.

... they will stick together and hope, that way, to continue to play a historical role. I think that is, quite frankly, the only way that Southeast Asia can continue to survive and continue to play a meaningful role in the history of the future.

Trump 2.0: Impact on Southeast Asia

Chow: Alright. Thank you. Now can we take a question from Kuala Lumpur? Can I have a question from KL, please?

Q: I’m Bunn Nagara from the Renaissance Strategic Research Institute and the BRI Caucus for Asia Pacific. What we’re seeing now around the world, series of recalibrations and maybe reassessments of partnerships and alliances, not all of which are based on Trump 2.0. But there are also other changes going on. For example, the rise of the global south, with BRICS, with G77 plus China, and we have revived G24 and so on, as well as the continued dynamism, economic dynamism of East Asia, despite all the odds.

I would like to ask, first of all, what does the panel think of the durability of this, all these changes, reassessments, if not also realignments in Southeast Asia? Going beyond the official statements of not choosing any side, and without actually having to choose any side. What are the likely changes in perspectives that countries in Southeast Asia are undertaking? And appending to that, would all these changes worldwide last beyond the four years of Trump 2.0? Thank you.

Chow: Prof Wang? Or Prof Huang?

Wang: Let me put it as briefly as possible. And that is that when I refer to earlier on to the Indo-Pacific possible alliance to contain China and puts the emphasis on the Indo-Pacific as a strategic region for a global contest, I also indirectly am saying… this puts Southeast Asia in an extraordinarily strategic position because it is right in the middle of both the Indian and the Pacific Ocean. As location, not by choice. Its very location makes it very central to whatever is happening in the kind of contestation that may come about between US and China in our region.

Trump 2.0 is different. Trump 2.0 is a global tariff war. Essentially you couldn’t arbitrage; you could to some extent, but compared with Trump 1.0, you couldn’t really arbitrage in a way that you did before.

By that locale… by being located where we are, we actually have a very special responsibility and a chance to play a very crucial role in maintaining the balance between the two powers. How Southeast Asia reacts, by speaking with one voice, by acting always together, it, and always in terms of the interests of the region as a whole, and not simply national interests alone, this could make a big difference to what happens to the US-China relations in our region.

And I believe that the ten leaders of the region are aware of that. They may from time to time disagree about the priorities, but they are fundamentally agreed that whenever it comes to something really strategic and vital to the region, they will stick together and hope, that way, to continue to play a historical role. I think that is, quite frankly, the only way that Southeast Asia can continue to survive and continue to play a meaningful role in the history of the future.

Huang: I think this is a very good question, and it is a question that forces us to make a distinction between Trump 1.0 and Trump 2.0. The Trump 1.0 was mostly about China, imposing tariffs on China. It was really de-sinofication of the economy. And as a result of that, as the questioner observed, the economic growth in the region still continued. The reason is because when you target one country, then capital moves around to solve that problem. So if you look at goods and capital moving around very very quickly in response to the way that you impose tariffs, if you look at the US import share of different countries from 2016 to 2023, China lost roughly in the order of 5% of the share of the US import market. And US import usually each year is about US$3 trillion; 5% is a lot of money.

And then if you look at the gainers, the biggest gainer is Mexico — roughly around 3%. The second biggest gainer is Vietnam, in this region — roughly about 2%. So essentially these two countries gained exactly the same amount that China lost. And then you go down the list: Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan — they all gained, and China lost. So essentially that kind of a trade rebalancing was able to keep the economic momentum going.

Trump 2.0 is different. Trump 2.0 is a global tariff war. Essentially you couldn’t arbitrage; you could to some extent, but compared with Trump 1.0, you couldn’t really arbitrage in a way that you did before. And there is discussion about restricting investments and restricting goods coming from Canada, from Mexico, and some of the goods coming from Mexico were produced by Chinese companies operating there. So we’re talking about something different. So I share the observation by the questioner in Kuala Lumpur about the past. I don’t share the optimism about the Trump 2.0 because it is a totally different ball game. And I think through the way that he has done this has surprised everybody — has surprised the Wall Street, has surprised automobile companies in the United States, has surprised the Silicon Valley people. And it’s a different ball game.

Chow: And I think he also asked whether the changes are fundamental, or whether they are short term.

There’s absolutely nothing that the legislature, the Congress can do if Trump stops enforcing the law passed by the Congress. If that is broken down, if the election system is broken down, that is going to be fundamental and longer term.

Huang: It would be fundamental if, so I think in terms of the economy, in my own mind, I have kind of written off the next four years, in terms of robust economic growth. I just think that’s a, almost a given now, that we’re going to have recession and shocks. In terms of the pillars, and so that’s why I really think that China has an opportunity to protect itself if it reforms the issues that I was talking about.

In terms of the long term, if the rule of law is undermined, and then this is the thing about the US, right? So there is a separation of power: The legislature, the court, and then the executive branch. There is a separation of decision-making power, right? Legislature is making laws, the court is making judicial decisions, and the executive branch makes… I guess executive decisions.

But it’s the executive branch that enforces the law, enforces the court decisions. In terms of the enforcement, there’s no separation of power. If Trump doesn’t carry out the court decisions, there’s absolutely nothing that the Supreme Court can do to enforce its decisions. There’s absolutely nothing that the legislature, the Congress can do if Trump stops enforcing the law passed by the Congress. If that is broken down, if the election system is broken down, that is going to be fundamental and longer term.

Chow: Thank you. Now we will take another question from Singapore.

The United States has a great history of rebuilding and reinventing and resilience, and we’re facing some real challenges that are existential that we need to address, and that’s what this administration is doing.

US intentions explained

Q: Hi, my name is Casey Mace, I’m the chargé d’affaires at the American embassy here in Singapore. I feel like it’s probably appropriate for me to stand up and offer a couple of thoughts. I’ll resist the temptation to defend the United States against all of the comments that have been made. But I do want to offer two thoughts that I think are important to recognise.

What President Trump and the new administration are doing is to address two structural problems, if not failures, that few people disagree with. One is that the United States federal deficit is ballooning, and it’s not sustainable. And the only way to address a government that’s spending beyond its means is to reduce our budget and reduce the size of our government.

The second challenge that is really more of a systemic failure is the trading system that has evolved over the last 60 years. Whilst it’s led to a lot of growth, it’s also creating incredible imbalances and a lack of equilibrium in the trading system. The United States average tariff rate right now is about 2.5%. China’s average tariff rate is up north of 6%, and the average tariff rates in Europe and Southeast Asia are even higher. United States trade deficit with China is US$300 billion. This region’s trade deficit with China is US$200 billion. So China’s surpluses with the rest of the world are kind of running away. And that system is not sustainable either.

So thank you very much for your comments, and I think the fact that you and I can disagree, makes me feel optimistic about the United States.

And so the new administration, what the United States is trying to do is trying to sort of restore some balance, so that trade can continue and sustain the economy. So I would offer those two thoughts. I would also end by saying I am optimistic for the United States. The United States has a great history of rebuilding and reinventing and resilience, and we’re facing some real challenges that are existential that we need to address, and that’s what this administration is doing.

Now let me ask a question. Given the fact that the United States is pursuing a policy of seeking to rebalance the trading system, I think it’s only fair to expect and assume that China’s trade with the United States, if not with the rest of the world, is going to be impacted quite dramatically. What do you think China’s response to that will be and should be?

Huang: So thank you very much for your comments, and I think the fact that you and I can disagree, makes me feel optimistic about the United States. So let me put it that way. I think the two points you made, I completely agree with the broad objectives that have been enunciated. No, not just by the Trump administration, but also by previous administrations. In terms of the federal budget deficit, US$36 trillion of debt, right? Huge percentage, times of the, about 250% of the GDP.

I sort of quibble with you little bit. I agree with your diagnosis of the problem, but I quibble with the view that “the only way is to reduce the federal government”. I think there’s definitely a way to reduce the federal government, but more methodically and in a more data-driven way. But, you know, there are other ways, right? So we can raise taxes on the rich people, and we can close the tax loopholes. The fact is that as the administration is cutting down the size of the government, they are also going to give tax cuts to the rich people, to the billionaires. And so it’s that combination that worries me. So if it’s just one of them, no. But it’s that combination.

So the view is that, you need to provide incentives to the rich people for them to work hard and create jobs. But at that level of wealth, I think the marginal, what the economists call the marginal benefit, is really not terribly strong, right? Look at Elon Musk, right? I mean, what he has been doing arguably has caused him lot of losses in his businesses, right? Tesla. And look at the stock price of Tesla. But he’s clearly not motivated by money; he’s motivated by something else.

In terms of the trade imbalances, I absolutely agree. But here’s the difference between using tariffs as an instrument to bring down the worldwide levels of protection vis-à-vis using tariffs as a way to deal with lots of other issues, right? So I do want to make a distinction between these two ideas about how to use tariffs smartly and selectively.

And I will also argue: if I were in the US government, I would do it one by one, rather than against everybody simultaneously. And identifying really the areas of the concern, and then work on that. And then, you know, deal with other countries one by one.

If in the next four years, the two countries can work out a practical, a pragmatic working relationship, rather than engaging in really strong rhetoric against each other, that’s a huge plus. That’s a huge positive.

China’s moderate response offers an opportunity

In terms of your question about how China can respond, I actually am pretty heartened by the fact that, this time around, the Chinese response has been more moderate and calibrated, unlike last time. So last time they really responded proportionately. But this time they have been very careful. They have been more selective.

I think if I were the US government, I would seize the opportunity to reset the relationship with China, and China is showing its willingness to — I think on other issues as well — to repair some of the relationship with Japan, with Europe, and with the United States. If there is a way to work out an agreement with China, to get China to cooperate on other fronts, and then, I would argue that the US should permit more investments coming from China in the United States, relax some of the controls that the Biden administration imposed.

If in the next four years, the two countries can work out a practical, a pragmatic working relationship, rather than engaging in really strong rhetoric against each other, that’s a huge plus. That’s a huge positive. And the Chinese leadership has become more cognisant of their own challenges they are facing within the economy. Export, last year they had almost US$1 trillion of this surplus. Export is one sector where they had been doing well, so you don’t want to sacrifice that so quickly. So that could be an opportunity. So on that, I’m mildly optimistic.

Chow: Right, thank you Prof Huang. I think we still have time for a very short question and some very short answers, from KL. Kuala Lumpur? Another question? Do we have a question from KL? Ok, if not, Singapore side? Yes, please. A short question, short response.

... if Singapore can be more forthright with the leaders in both countries, and Singapore has that credibility and respect, I think it will be good for Singapore to be more direct, to be more frank in conversations with Chinese leaders and American leaders.

Singapore has a role to play

Q: Good evening. Hi, I’m Marcus, I’m an economics student. I was curious if I could get an opinion from the panel. So Senior Minister Teo just now raised how small states should try to exercise its agency by trying to engage with all sides and to help steer the international system away from confrontation. However, what if certain international actors don’t seek to act in as rational a way as we usually like? And how could being overly accommodative set an unintentional precedent? Following this, how does small states balance the need to be open and engaging without being overly accommodative in the face of potentially unproductive behaviours on the international system? Thank you.

Chow: Prof Wang? Do you want to respond?

Wang: (to Prof Huang) Leave it to you.

Huang: But I came from two large countries. Born in one and studied in the other. So I think for smaller countries, like Thailand, Singapore, countries in Southeast Asia, I would choose policy neutrality between these two countries, and not to be overly directional toward either one. But I also think that Singapore has really tremendous discourse power. Right? Singapore is really respected in China. It is also respected in the United States. Singapore model is really very well known and the country, the way that the country has managed the past economic challenges; first, has grown the economy and managed the economic crisis, like the 1997 financial crisis and the recent Covid crisis, really set the example for many other countries.

So I think if Singapore can be more forthright with the leaders in both countries, and Singapore has that credibility and respect, I think it will be good for Singapore to be more direct, to be more frank in conversations with Chinese leaders and American leaders.

And I totally agree with Senior Minister’s remarks about cooperation, collaboration, and about telling the big countries about the perception in this region of the actions that they take. Yes, the US has a big defence budget, but China doesn’t have a small defence budget relative to the size of the countries in the region.

It is going to be viewed with a certain perspective. So I don’t really know what, behind-the-door conversations are like, but the thing that I have seen is that sometimes the American business community would not be direct and frank when they communicate with Chinese leaders about the issues that they face. And then they turn around and, you know, they say this, they say that. But in front of the Chinese leaders, they are usually not communicating directly.

So, in that type of political system, the system is not designed to maximise information flow. The system is designed to minimise information flow. And so it is a rare opportunity for foreign leaders from business community, from political community to be able to have direct conversations with Chinese leaders. I cannot have that. Chinese academics cannot have that. Right? So, you know, Singapore, I really respect Singapore so much, that I believe that Singapore can do it.

Chow: Alright. Thank you very much, Prof Huang. Well, due to time constraints, we have come to the end of the Q&A. Thank you Prof Wang, Prof Huang, and Prof Ngeow for such an engaging and illuminating session. I’m sure all of us have some questions answered, but we’ll still have many many questions on our minds. We will be publishing two in-depth interviews with Professor Wang and Professor Huang on ThinkChina, so keep reading and watching ThinkChina to find out more. Thank you everyone.