[Video] Professor Robert Ross: US-China rivalry is a battle for Asia

In this interview, Professor Robert S. Ross, who teaches political science at Boston College, discusses a wide range of topics — such as US-China relations, internal and external issues faced by the US and China, and changes to the global geopolitical landscape — with ThinkChina editor Chow Yian Ping. The following is an edited transcript of the interview.

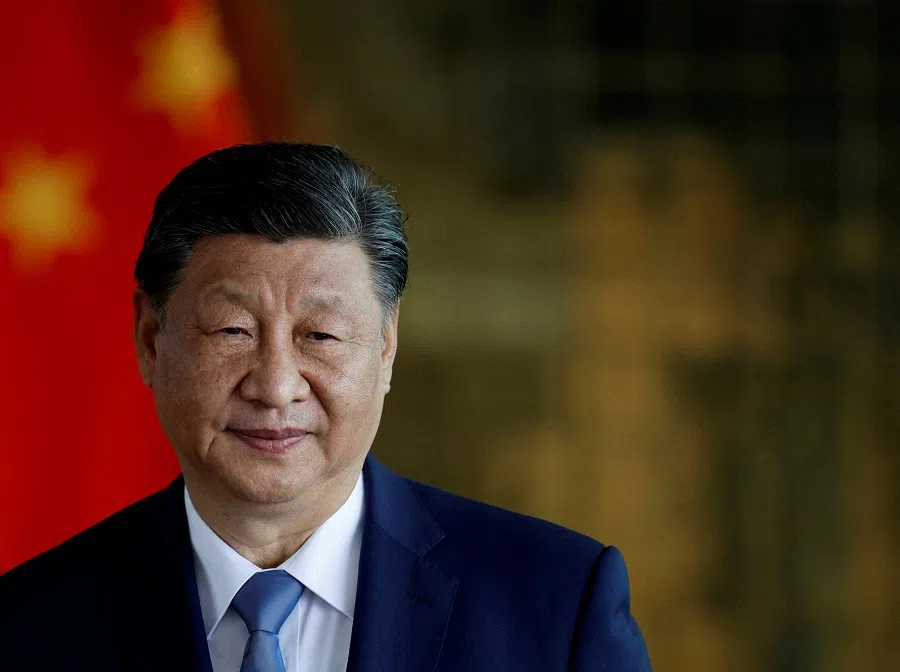

On one side of the globe, newly elected US President Donald Trump aims to make America great again, while on the other, Chinese President Xi Jinping foresees the rise of the East against a declining West. Both leaders face domestic challenges and foreign relations issues. In this era of disruptions and unpredictability, who is better positioned to lead the future world order? What could derail China’s current development trajectory?

The ThinkChina team travels to Boston to speak with Professor Robert Ross, a political science professor at Boston College and an associate at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University to gain his insights. Prof Ross’s research focuses on Chinese security and defence policy, East Asian security and US-China relations.

Chow Yian Ping (Chow): Thank you Prof Ross for this interview with ThinkChina. I want to start with President Trump because you know, that’s where the attention is these days. He’s making moves at dramatic speed both at home and abroad, and it’s very hard to keep up. We are seeing government layoffs, funding cuts, tariffs, plus issues with Russia and Gaza being addressed. Can you explain why things are happening so fast? And how far-reaching these changes are? Because many of us are worried that these actions seem to be happening without much oversight.

Robert Ross (Ross): Well, he’s very difficult to explain; this is true. And it does often seem that he speaks without thinking, and so often, he has to retreat. So we’ve seen some retreats recently on the part of the National Institute of Health, the US military, the post office and other areas – he says things, and it seems as if his advisers and members of Congress are saying, “That’s not particularly wise; can we go slow on that?” We’ve seen that on the trade wars too, on… tariffs. So he seems to just talk without thinking because he’s angry or because he’s impulsive, and his advisers don’t have much input – only after the fact. So people have to come along, if you will, and clean up after him after he makes mistakes that are neither good for him nor for the country.

Trump and US foreign policy

Chow: Do you see an overarching plan regarding his foreign policy or how he’s running the country? We know “Make America Great Again”, do you see, whatever he’s doing is bringing it in this direction?

Ross: Well, I think part of the issue for the United States is: after the post-Cold War period, the United States was so powerful, capable of leading the world, then many feel the United States is paying a high price for this leadership. And this is undermining the American economy, undermining our competition with China. And so much of what you see from Donald Trump is saying, “We don’t want to pay the price for this. This is too costly to us. We must focus on our resources in the United States.” And many Americans might agree with that.

Many Americans might think it’s time to come home from Ukraine and try to end that war, end American activities and hostilities around the world. The problem is that it’s not the objective that is necessarily a problem; it’s how it’s going about it.

So on the one hand he’s burning bridges with countries that could be valuable to us if you want to contend with China. NATO’s important. EU is important for having cooperation on trade and technology. But he’s so focused on retribution, on correcting what he thinks are wrong, that he doesn’t have a large strategy from a global perspective.

Second, I think he looks at countries like NATO or Ukraine and says, “What do I need to compromise with these countries for? They’re not very important. They depend on us.” So from that respect, the only countries he respects and wants to negotiate with are those that he thinks matter and can shape America. So that might be China. That might be Russia. But other than those countries, he seems to disregard them as unimportant, not worthy of consideration. So, again, he can be impulsive.

So in many ways, he’s undermining his own objectives by his impulsiveness; he’s unwilling to consider how to build coalitions, unwilling to consider the interests of other countries other than Russia and China. — Professor Robert Ross, Political Science Department, Boston College

Chow: So is he trying to settle these neighbouring countries and allies first, before he can set the stage to actually go tackle or contain China?

Ross: Well, I think the sequencing would impute too much logic to what he’s doing. Because he’s doing everything at once. So the American ability to correct the trade relationship with China is undermined if Europe will not participate. And Europe will not participate if they lose the American market, then the Chinese market becomes more important. The Europeans will have cooperated on electric vehicles if the Americans are not going to cooperate on Ukraine. So the idea of coalition building is alien to him. And of course that undermines American security. It undermines stability in Europe and Asia. While he’s trying to manage Russia and China with less global support.

So in many ways, he’s undermining his own objectives by his impulsiveness; he’s unwilling to consider how to build coalitions, unwilling to consider the interests of other countries other than Russia and China.

Chow: But I mean the US, in terms of foreign policies, is not just dictated by Trump alone, so he has his administration to actually help him come up with all these ideas. So how could that be that it is all directed by his own impulsiveness and there’s no bigger thinking of the whole perspective?

Ross: Well, of course like the United States and other countries, primarily the leader, the prime minister or president has almost unchecked power to carry out diplomacy. And Trump was like that. But some people think Trump listens to his advisers, maybe the last person he spoke to. I don’t see him that way. I think he’s very confident — overconfident, perhaps cocky. He knows what he’s doing. So his advisers are not there in the decision-making process. They have to come in afterwards and say, “You might want to slow this down.” Same thing with Congress. Of course, he’ll be going to keep an eye on public opinion, and there is a pushback in public opinion — we’ve seen this recently. Republican members of Congress who support him are being criticised more. The opinion polls are slowly dropping —– he’s very low on the opinion polls for a first-term president, right after the inauguration. So maybe he will listen to that as well. But I’m not sure.

People told him he was wrong in the past — he needs to move to the centre in order to get elected, and he never did. So he talks to his base, and he thinks his base, which is very pro-Trump, very “America First”, very isolationist. He talks to that base and thinks that’s sufficient, that’s all I need to maintain my popularity.

Are businessmen exercising undue influence on US politics?

Chow: And people are also talking about business moguls actually getting deeply involved in governance, like Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk has been called “First Buddy” by news outlets. And the US entering this “broligarchy” era. He’s also working on DOGE, which is behind all this cost-cutting and layoffs in the government agencies. What is your take on this? Involvement of the tech [moguls].

So if we want to watch who matters in this administration, you don’t want to see the former politicians who, again, Trump doesn’t respect politicians, who do we focus on? Who does he respect? It’s the business people, from Wall Street, from the tech sector. — Ross

Ross: On the one hand, President Trump’s long career and since certainly his first term, he has very little respect for government bureaucrats, very little respect for diplomats, or experts, or even generals in the Pentagon. Clearly all the people he respects are successful business people, whether this is Wall Street, whether it’s the real estate industry in New York, whether it’s the tech people in California…and Elon Musk is one of those people. So he’s staffing his most important positions with people from Wall Street, from the business community. That would be Treasury, that would be Commerce, and other important positions.

It’s not clear he listens to them, but they are the most responsible people in his administration. Now when it comes to Musk and the economy and the government, he has unchecked authority to simply fire people at will without apparently consulting with either the president, members of Congress, or the advisers, and there is beginning to be a pushback. This is someone who is not elected, not confirmed by the Senate, just a friend or employee with what appears to be unchecked power. So this is a concern to many people. And even if the courts were to say… Elon Musk is exceeding his authority, it’s not clear that either he or Trump would stop what they’re doing.

Chow: So you think he’s sidelining all the rest of the sectors and then putting his own… whatever he wants to trust in the business sector?

Ross: The people he respects as advisers are going to be people from the business sector. So on the one end, we see former politicians in the intelligence community or the Pentagon — they do not have their own autonomy. They are dependent on Donald Trump for their careers. They must be loyal. And they are not going to challenge him. Whereas these people from the business community, quite successful in their own right, well-respected in their communities, and they, if you will, can speak truth to power better than these people in the NSA, DOD, and intelligence community. So if we want to watch who matters in this administration, you don’t want to see the former politicians who, again, Trump doesn’t respect politicians, who do we focus on? Who does he respect? It’s the business people, from Wall Street, from the tech sector.

Chow: So are you worried about the direction that the US is heading under the Trump administration? And, you know, this skewed way of depending on the business sector?

Ross: Well, I have two concerns generally about the direction of America under Donald Trump. One of which is our foreign policy. We can all agree that America needs to do less in the world. We’ll be less proactive in international conflicts and wars and hostilities. Many of us agree that Asia is of primary importance and that, if you will, Russia is not a very big challenge. After all, Russia depends on North Korea for artillery and troops. Uhm… how powerful can it be if it’s relying on North Korea? So many of us will agree we need to move in a different direction. And many of us might believe we need to have better border policies.

But it’s more of the extreme initiatives he’s taken, the impulsiveness, that’d lead us to be concerned about internationally, what’s going to happen to American ability to cooperate with other countries to achieve our objectives? So European interest in cooperating with us is declining daily. Our aid programme is ending. Well, we’re trying to compete in the West Pacific, but if West Pacific countries are unable to receive American assistance, they will turn to China. So all around the world, we see Trump drawing back, isolationist, cutting funding for critical programmes. And so American isolationism will not help the United States deal with its international problems. Well, it’ll actually undermine American security.

And domestically it’s the same thing. We see the president having initiatives that are concentrating executive power, concentrating authority in the White House, in his office, that no other president has done. And we worry about the constitution. So the policies are one thing, but the concentration of power, the unilateral initiatives — many are worried about the direction of the country and the stability of our democracy.

This is a retreat, not only from leadership, but from simply participation. And so if any country is undermining the rules-based international order of states, it’s the United States... Now, American decline is reflected in that because there is resentment at the cost of leadership. — Ross

Trump’s ‘America First’ ideology and its impact on the global order

Chow: So people outside of the US, they will be saying things like, the US is actually pulling back from its usual role of leading this rules-based order and pushing for prosperity through globalisation and free trade. How do you see this shift? Because some people are saying that this could be the start of the US decline.

Ross: I would say certainly… it’s difficult to avoid the word “isolationism”. If you look at every international organisation, even the ones the United States helped to create after World War II, we’re taking away our funding. Whether it’s the World Health Organization, whether it’s the WTO. This is a retreat, not only from leadership, but from simply participation. And so if any country is undermining the rules-based international order of states, it’s the United States — by ignoring those rules, cutting the funding, and withdrawing participation. Now, American decline is reflected in that because there is resentment at the cost of leadership. But again, it’s possible to renegotiate these… America’s role, to renegotiate leadership and maintain support for that system. That’s not what Donald Trump is doing. He’s not trying to make room for China, make room for other countries to renegotiate this order. He’s simply withdrawing off completely in an isolationist manner. That poses the greatest threat to international stability, and rather than China, in terms of the rules-based international order, and that’s a great concern.

Chow: Do you think he sees it happening?

Ross: I don’t think Donald Trump cares. So when Donald Trump says… “America First”, he means that… Americans’ interests are not in leading the world. They’re in putting America… its own house in order and returning money and troops and people back to America. And second, he has such disrespect for other countries, and I don’t think he understands how important American participation in the world, support for international organisations, foreign aid, foreign trade, how important that has been for American security and economic prosperity. So I think he’s, in many ways, just oblivious to the implications while simultaneously running roughshod over the institutions.

The decline of soft power?

Chow: We are also seeing that Donald Trump and Musk, they have been criticising US legacy media. The US media has been seen as a fourth estate, and it has actually been advocating for American values and agendas overseas. But we see a lot of attacks on US legacy media these days. How do you see that? The impact on the US media landscape and also on US soft power? US legacy media is a source of US soft power.

... we are the most protectionist of the great powers; our foreign aid programme is disappearing; January sixth and our authoritarian leaders undermining American prestige in Europe; our gun culture and violence is not respected around the world; America’s drug problems with fentanyl is worse than any other country in the world. So American soft power doesn’t look very good these days. — Ross

Ross: So Donald Trump takes offence at anything that criticises America. Now, many feel that’s America’s great strength, in that we are able to criticise ourselves and that our media can be open to different voices. He clearly opposes that. So the Associated Press was banned from press conferences ‘cause they wouldn’t say “the Gulf of America”; they say “the Gulf of Mexico”. We have new leadership in the Voice of America. That has many people worried –— that Voice of America will be the voice of Donald Trump rather than the voice of America. So yes, this is a major concern for America’s role in the world and for… not the values of America in… writ large, but the values of our media and our society that can communicate in openness and the willingness to accept debate.

Then more generally, American soft power is suffering; it’s been suffering ever since Donald Trump’s first term. His first four years in [office]… President Biden did not help, and now it’s going to continue to decline because America’s reputation in the world, how others see us, is less favourable than it used to be. So we are the most protectionist of the great powers; our foreign aid programme is disappearing; January sixth and our authoritarian leaders undermining American prestige in Europe; our gun culture and violence is not respected around the world; America’s drug problems with fentanyl is worse than any other country in the world. So American soft power doesn’t look very good these days. And of course that media is part of that – the control of the media, control over the voices that America expresses.

Chow: What you just shared sounds quite alarming. Because of this declining of soft power, where do you see it going? It sounds really bad.

Ross: Well, for many countries, the issue of war and peace and security and militaries are less significant than economic development and contributions to their own welfare. When America pulls back from that, they’re only going to have one place to turn, and that’s to China. After all, China’s Belt and Road is quite successful in building infrastructure around the world. China’s aid programme in the West Pacific is quite generous. So the money is there to do things that America’s not willing to do. The markets are open – free trade agreements with ASEAN, free trade agreements with many East Asian countries and with Latin American countries – while America is closing its borders. So that affects America’s reputation around the world.

As a country that doesn’t want to contribute to the welfare of the world, it doesn’t have much to offer the world. And so that is a major change in American soft power, and that undermines America’s ability to achieve its objectives through cooperation because countries will look at us and say “we don’t respect you” or “we don’t appreciate your values”, and that makes simply wanting to cooperate… less likely.

Chow: So you see these changes that are introduced by Donald Trump, as fundamental changes in US governance and its global engagement? It’s fundamental changes; it’s not just temporary shifts?

Ross: Well, the general direction is fundamental. A smaller footprint around the world, wanting to renegotiate the agreements after World War II, whether it’s trade or finance, that’s fundamental. America experiencing decline; its unwillingness to assume the burden of leadership. It will be very difficult to repair the damage Donald Trump is doing to our relationship with Europe and our international institutions. Because our reputation is declining, and countries feel maybe they cannot count on us or are less reliable. And if they can’t rely on us, then they’re going to cooperate less with us because they don’t know whether agreements will hold in the future. So you’re going to see more and more countries going their own way rather than cooperating with the United States.

In the absence of the US, China steps up

Chow: And just now you were saying that China could actually step up to fill up the roles that America has been playing. How do you see that happening? Do you think that China can actually play a much bigger role in this?

Ross: Well, of course, it depends on the region. But in much of the world, China is welcomed as a contributor to economic development and infrastructure building. We all know that Chinese movies and food is welcomed around the world, and their film industry is doing quite well. They are attracting investments or imports from countries around the world. So China, we have long said is the engine of growth, and its economy is growing so much faster than much of the world. Even today, it has slowed down but still growing faster — twice as fast as Europe, maybe growing twice as fast as the United States — with a market that’s three, four times larger than the United States and Europe. So it is going to fill that role inevitably as the major economic power in the world. And as long as it’s growing and benefitting from the current system, it is more willing to support it. Unlike the United States, as a declining power, sees this system helping China. And that is very much why we are reconsidering our support: Because we see it contributing to the rise of China, and, relatively speaking, that means the decline of the United States.

Chow: But China is also facing a lot of challenges, including the high [local government] debt levels, the demographic shifts, geopolitical tensions and of course a lot of people saying that… President Xi Jinping has actually extended the term limits, and there is no longer any term limits. So there are a lot of changes on China.

Ross: You’re absolutely correct. China has many significant domestic problems. So we have… a growing role of the state in the private sector — that’s a big problem. We have slow growth last three or four years. We have reduced foreign investment, savings rate remains very high, protectionism against China in the United States and Europe is a big problem. America’s tech war against China is a great concern in China. So both countries have significant problems.

America’s debt problem is worse than China’s. China’s still growing twice as fast as the United States. So we have to really ask ourselves: If neither country’s doing very well, which country might be doing better? Now, in the short term, the United States is doing much better than Europe and many other countries. But it’s not clear that we will be able to reduce the growth of Chinese economy, and its technology going forward. So if you look at the US-China competition, that’s a very unclear future. And we know we can have confidence that they know how that will turn out. I think for all of us, what we want to hope for is that neither country fails and neither country can achieve hegemony. We’d like to see both countries play important roles in the world. That would be best for everyone. But I think the future remains uncertain, particularly as it relates to the South China Sea and East Asia.

I think the likelihood the United States and China stabilise a relationship as two great powers is highly likely. America’s not going anywhere, and China will continue to rise, and eventually it’ll stabilise. — Ross

Is a partnership between the US and China possible?

Chow: Do you see that there’s a possibility, there’s a potential of it happening? You know, both countries actually working together to make something happen? Actually Donald Trump mentioned a better, bigger deal with China. He wants to achieve this?

Ross: Well, I think the likelihood the United States and China stabilise a relationship as two great powers is highly likely. America’s not going anywhere, and China will continue to rise, and eventually it’ll stabilise. Donald Trump would like a new trade deal with China. Obviously, because a trade war with China would be very detrimental to the American economy. So whereas he treats Europe with disrespect, he treats China with respect because China has the ability to influence his own leadership in the United States, because it can influence the American economy. The details need to be worked out.

I think the Chinese have signalled very clearly that they feel they have leverage. They’ve been exercising that leverage over rare earths, over investments in American investments in China. So they’re going to want a deal that is perhaps not satisfying enough to Donald Trump. And whether which side would compromise and how much, we’d have to wait and see. But I think China would like an agreement as well because they’d benefit from stability, they’d benefit from exports, and they’d like to continue to grow.

The US and China remain plagued with pressing internal issues

Chow: We see all these issues with America. But what is one potential factor that could disrupt China’s development trajectory under President Xi and CCP?

Ross: Well, we have short term and long term. I think in the short term, the Chinese economy needs to begin to develop and grow. In some respects, that would have to reflect the growth of the international economy so that exports can grow. Many countries in Europe remain in recession. Much of the world does. So if the world comes out of recession, China’s exports will grow. The Chinese people still have a very high savings rate after Covid, and they will start spending again. And so that will also stimulate growth in the economy. So I would think that in the next year or two or three, China’s economy will begin to grow again.

The longer term is: how robust is the private sector? Is it willing to take risk for investment? Does it trust the party to allow it to accumulate wealth? Now there’s a lot of doubt within China as to whether it is secure and safe for the private sector to take risks. Just recently, I think Xi Jinping has made clear that he understands that the private sector, the entrepreneurs are very nervous, and he has tried to reassure them just recently that they can count on him to protect their interests. This is a fundamental shift, which before, Xi Jinping would say party stability, party leadership, grow the economy. Now the first thing he says is: grow the economy. And pressing the private sector and entrepreneurial. So he knows that he needs to reform this. Whether it’s successful, we don’t know.

Now the United States. We need to reform our debt issues. Our federal debt is just eating up our economy. It’s going to catch up to us eventually. Our Congress cannot either raise taxes or reduce spending. Our system is polarised. So we both have severe problems. I think no one can take any comfort from the problems of the other.

Chow: So which [nation] do you think is the highly possible candidate to actually come up with a new way of engaging the world and, maybe providing the kind of services that the world needs, and become the leader in that sense?

Ross: Well, I think if Donald Trump continues his policy towards Europe, the Europeans would have no choice but to cooperate with China and stabilise the system. So this would not be necessarily a new system, a new order reflecting Chinese values or interests, but a reform of the current system at the margins so that it better reflects China, but still we maintain the stability of the trade system, the stability of the World Health Organization, for example.

So the way things are going, the world would depend more on China to make that happen than the United States. And should the US policy towards Europe and the other advanced industrial countries continue, they will be less inclined to resist trade cooperation with China because Chinese retaliation will be all the more severe if they lose the American market. So we see Europe trying to resist Chinese exports, but I would imagine that would decline and it would be more welcome to Chinese exports, should Trump continue his policies. And that would be greater China-Europe, China-Southeast Asia, China-South Korean cooperation, and that will anchor the international trade order and international institutions.

... what we’re seeing is the [CCP] trying to manage two things at once: To give greater latitude to the private sector while maintaining party control. — Ross

The CCP’s relationship with the private sector

Chow: But just now you were also saying that for China to make sure it has this continued trajectory of development, it will also need to manage its relationship with the private sector.

Can it manage its relationship with the private sector without going through some kind of political shift or tweaking its political system in some ways?

Ross: The Chinese Communist Party plays a pervasive role in the Chinese economy — state sector and private sector. And that inevitably is going to cause suspicions, apprehension in the private sector about the potential for long-term investments and the stability of long-term investments. That will remain an obstacle to Chinese economic development; there’s no question. But what we’re seeing is the party trying to manage two things at once: To give greater latitude to the private sector while maintaining party control. That’s a very difficult process. We’re not at all clear that they can be successful. Xi Jinping recognises the problem, that’s clear, but whether the private sector is willing to cooperate, given its past experiences of the post-Mao era, of the sale of enterprises and the government coming in and restraining the private sector, they can’t be too optimistic that going forward that will not happen again. So this is a major problem for China’s long-term growth. But again, I mean, there’s a lot of uncertainty in the world.

Right now the prospects don’t look good that the US Congress will be able to pass legislation because the Republicans and Democrats do not talk to each other. They don’t vote. There’s no likelihood that we’re going to be able to do anything about the federal budget and the federal deficit because the two sides will not agree to any compromises that can make a difference. I think both countries have a great deal of uncertainty. And Americans will say, you know, “I have faith in America.” But faith in America won’t solve your problems. And the Chinese will say, “We’ve found a new way to develop.” But that won’t solve your problems.

How will Trump handle the Taiwan issue?

Chow: I want to draw your attention to the Taiwan Strait, regarding the Taiwan Strait and Taiwan’s status. Do you see a shift in how the US under the Trump administration will actually tackle the Taiwan issue?

Ross: Well, since the first Trump administration, the United States has adopted a more pro-Taiwan stance regarding cross-strait relations. And this is part of America’s effort, if you will, to contain China. We strengthen cooperation with Taiwan, the Philippines, South Korea. And this has created, to some extent, some instability in the strait because as we give greater support to Taiwan, the mainland is nervous that an emboldened Taiwan leadership could move closer to independence. So much of the activities we see in the Taiwan Strait reflect mainland efforts to deter the Taiwan leadership from moving towards independence.

In reality, America can do two things at once. It can promote stability in Taiwan Strait, constrain Taiwan from challenging the “one China” principle, constrain China from coercive policies towards Taiwan. It can do both at the same time. — Ross

Donald Trump doesn’t want conflict over Taiwan. He doesn’t want hostilities over the Philippines. He wants to end hostilities in Gaza. He wants to end the hostilities in Ukraine. There is a contradiction in American policy. ‘Cause on the one hand he wants to cooperate with China on trade, he wants to stabilise relations. On the other hand, China is our competitor. And so our partners in East Asia are significant for American security, and strengthening those relationships are part of American security policy. It’s not clear how he manages those two issues. Should he improve relations with Taiwan significantly, one would expect the mainland would become more difficult in the Taiwan Strait. And that would put pressure on the president to have greater trade and technology sanctions and increase the cold war climate. So I think he does not want to provoke greater tension in the Taiwan Strait. But I think he does not want to show weakness either. ‘Cause Donald Trump, if anything, believes that weakness is the most cardinal sin. Never apologise, never show weakness. And so a compromise on Taiwan may signal, he might fear that he is showing weakness towards China, and that America must accommodate to the rise of China. So that will be difficult for him also.

In reality, America can do two things at once. It can promote stability in Taiwan Strait, constrain Taiwan from challenging the “one China” principle, constrain China from coercive policies towards Taiwan. It can do both at the same time. We can maintain weapon sales to Taiwan while trying to restore some stability. Our climate today makes that more difficult in the United States. ‘Cause any sense that we are restraining cooperation with Taiwan is a political liability for the White House. I would suggest that’s where we should go. I think Donald Trump would like to do that too. But whether or not his advisers agree, and whether or not he has the personal character necessary to make compromises with the mainland on Taiwan, we have to wait and see.

Chow: But isn’t that, in a way, considered as some kind of good news? In terms of peace. Because he is actually looking at wanting to improve trade and trying to minimise hostilities. So that in a way, is actually good news for Taiwan and also for the South China Sea.

Ross: Well, many in Taiwan will worry that a US-China agreement might sell out Taiwan. And of course, they should worry. You know, it’s a small island 90 miles away from China. Without American support, they’d be very vulnerable to Chinese power. So America must find a way to reassure them that we will stand with you, while simultaneously urging restraint on them — less proactive arms sales, less proactive diplomacy, less proactive defence cooperation with Taiwan. Need to do both at once. I believe that’s possible.

But that would be a major shift to American policy since the last eight years. To begin to move toward greater self-restraint in cooperation with [Taiwan]. Now, if we can go in that direction, that would be good for East Asia. The Taiwan issue can be managed. No one wants to see increased tension in Taiwan Strait. Similarly, no one wants to see increased tension in the South China Sea. I think most countries would like to see the United States and China manage their relationship in a way that two great powers are going to compete, but they’re also going to find ways to avoid tension and escalation. That should be the objective of the Taiwan Strait. America’s found that difficult to do for the last eight years.

I might also add that given that Taiwan is 90 miles from the mainland, ultimately it must find a way to get along with the mainland. There is no choice. So America may be trying to… maintain its cooperation with Taiwan, to embolden Taiwan to resist the mainland. But that over the longer term, I don’t believe is a feasible policy. So once again, there should be an opportunity there for the United States to try and balance that relationship — have greater restraint on the one hand, but reassure Taiwan on the other hand.

Trump’s approach to dealing with China

Chow: I know you mentioned it is very difficult to predict how Donald Trump is going to shape its foreign policy towards any countries or even China. But I would like you to further explain: How do you think he will actually act on China?

Ross: You know, we can see already, in this administration, that the channels of communication are open. The commerce secretary, the treasury Secretary, and the White House are given to open dialogue with Xi Jinping. So they’re trying to find ways to stabilise this relationship. They hope for a trade deal. Donald Trump has his interests. He wants greater cooperation on fentanyl. I think the Chinese would be willing to do that. They would like to see greater American restraint and less tariffs going forward. I think Donald Trump is prepared to do that for a trade deal. I think Donald Trump is able to say, “I have just signed a beautiful trade deal with China. A grand trade deal that’s in the American interest. And I have been successful as a great negotiator in reaching an agreement that’s good for the world and good for America.” He is a great salesman to his base. So I think he can reach an agreement, make the compromises. China would agree ‘cause it wants to stabilise trade and then sell that to the American people as a victory for Donald Trump.

Chow: Mhmm. Do you see that as a good thing for America and for China?

Ross: I think it’s a good thing for America. I think a trade war with China has a very uncertain outcome. But I do know it would be very costly for the American people – higher inflation, higher unemployment. Higher inflation from tariffs, higher unemployment as China retaliates, and of course, Chinese controls over rare earth exports and the implications for American industry. That’s all bad for America. It also of course is not good to have, one of the costs of American policy today is a greater risk of war. We’ve all talked more about the greater likelihood of war in Taiwan Strait, of the greater likelihood of war with the Philippines. It would be good if we didn’t talk that way. And if we could lower that… the temperature. So I think that would be good for America too.

It’s certainly be… it would be good for China. I think China’s made very clear in its diplomacy with Europe and the United States that it doesn’t want trade wars. It doesn’t want to undermine the WTO. After all, peaceful rise has been good for China since the death of Mao Zedong. And China still sees itself as a rising power. So that system that helped it to grow? It has an interest in maintaining that system. So I think there is a basis for an agreement. Donald Trump would like to avoid a trade war, so would China. It would be good for the United States.

There’s no reason why the United States should not have Chinese investment in the United States to build electric vehicles, create American jobs, help American industry, help the GDP, contribute to taxes to the government, and have technology transfer. That’s what Europe is doing. So the Biden administration said no, no Chinese EV exports to the United States, no investment. We do not allow investment of solar panels. I guess solar panels are old technology; they’re very basic. So we have taken the trade war to the extreme, where it doesn’t hurt China but only hurts the United States. I think this reflected in many ways, the Biden administration’s long-term strategy to defeat the rise of China. And so it was an across-the-board trade war, an across-the-board tech war.

If we can restrain that and begin to have a targeted technology policy which has… these are critical technologies; we need to protect them. That would be much different than what we’re doing now. While there are certain critical industries that the United States must defend and protect, but not the entire American economy. That’s the direction that is open to America, and maybe Donald Trump is prepared to do some of that to reach that trade agreement with China and avoid a trade war and instability.

And again, this is very much Donald Trump — he doesn’t have a grand strategy for American security. He thinks issue by issue. — Ross

Chow: From what you have shared, it seems like the Donald Trump administration is more an issue for the neighbouring countries and their allies rather than for China.

Ross: Well… China is worrying that the United States can use its leverage to influence the European countries towards China. After all the tech war, the Netherlands is restraining cooperation with China. So is South Korea, so is Japan. And China is working very hard to try and undermine American diplomacy in Europe. ‘Cause it would be very damaging to the Chinese economy if America could create a trade and technology coalition comprised of Europe, South Korea, Japan, and other countries. So it has major implications for China as well.

This of course is one of the issues for the Trump administration. He said it wants to cooperate with China, but then it’s undermining cooperation with other countries. So that in many ways… bilaterally, the Trump administration could be quite difficult for China if there’s no new agreement. But multilaterally, the Trump administration is good for China because American isolationism is helping China. America’s reduced role in international organisations, the WTO — the World Trade Organization — is helping China. America’s trade conflicts and defence conflicts with NATO, that’s helping China. So multilaterally, America is shooting itself in the foot, while it’s trying to compete bilaterally. Of course, this is not a sound strategy for American security.

And again, this is very much Donald Trump –— he doesn’t have a grand strategy for American security. He thinks issue by issue. He thinks about economics and American economy. He thinks about winning and losing in a bilateral relationship. Don’t show weakness. But that big perspective of how you would advance America on a global stage? He doesn’t have a strategy.

Is US dominance at an end?

Chow: With all these things happening and in this era of flux, where do you see the future of global society? China has been talking about the rise of the East and the decline of the West, whereas the US, as you said, wants to make sure America is great again. So where do you see this global society moving towards?

I think, going forward to the future, perhaps China will not dominate East Asia, but certainly the end of American dominance. That’s a likely future. — Ross

Ross: Well, we look at the US-China competition. This is a competition in Asia. It’s all Asia. So we’re not worried about Chinese presence in the Western hemisphere. Donald Trump could talk about the Panama Canal, but it’s really not very serious. America’s going to be a major player in Europe. Whether we cooperate or not, we’re going to be a major player. The competition is in Asia.

So we’ve seen countries in Asia who live close to China in proximity, who depend on the Chinese economy becoming more and more cooperative with China because America is less reliable; our military is relatively declining — our navy; and our markets are less important to growth in the region. So these countries, many of them are moving, if you will, between the United States and China. They’re not going to align with China, not going to become… in China’s sphere of influence, but they’re moving away from aligning with the United States. That’s the competition.

So when China says China, the East is, you know, found a new way, they’re saying China’s competition with the United States’s in East Asia. And China is succeeding. And I think in that respect, there’s a lot of truth to that. If you look at the 14, 15… governments in East Asia, only four of them aren’t cooperating with China today. That would be South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and the Philippines. And yet of those four, three of them the governments keep changing, and they keep changing their policies. So there’s only one country left in East Asia that’s a reliable American ally: that’s Japan. And I think, going forward to the future, perhaps China will not dominate East Asia, but certainly the end of American dominance. That’s a likely future.

Chow: And do you think Donald Trump, would he do something to reverse this or to try and change this? Does America still have any chance of changing this?

Ross: America has a problem similar to other advanced industrial countries. We have first built up our infrastructure in the 50s and 60s. Then we built up a healthcare programme and a welfare programme, social security, Medicare, and Medicaid. And now, our entitlements are welfare programmes, and the interests of our debt are about two-thirds of the American federal budget. And they cannot be changed without new legislation in Congress. The American Congress is not happy to do a new legislation. So where do we find the funds within our budget to revitalise the American economy, the American infrastructure? Where do we find American defence capability?

So one interesting statistic is: China produces close to 50% of the world’s ships. America no longer has a shipbuilding industry; we only produce about 0.5%. And where will the funding come from? Where will the private sector funding come from? To rebuild America’s shipbuilding industry? China’s very good at technology. Can we compete in technology? So it’s not clear how America, going forward, will be able to compete with China to maintain American hegemony.

On the other hand, it’s quite clear the United States will be a great power, will maintain a role as a great power in the world, but in East Asia that competition will become much more difficult to manage as China continues to rise and America continues to face serious constraints on its expenditures. After all, China doesn’t have a large social welfare programme for its budget. China’s military doesn’t have a volunteer military, so that its labour costs are much lower. So its ability to compete, simply with even a smaller budget, is quite strong. And that’s the challenge for America.

America doesn’t need hegemony in East Asia in order to be secure. America’s still going to be a great power in the Indian Ocean, the Western Pacific. So that the rise of China in sharing power in East Asia is not something that America will feel it has to risk a great power conflict over. — Ross

A new era of great power rivalry

Chow: So the power gap between the two will actually narrow, meaning that there would be some kind of a conflict that you cannot avoid.

Ross: Well yes, I think certainly the power gap will continue to narrow between the United States and China. China’s economy will continue to grow faster than the US economy. Chinese military will grow faster than the American military. That’s the trend for the next ten to 20 years. The former National Security adviser made clear that to rebuild America’s defence industry would take 20 years. A generation. Twenty five years. So that gap will continue to narrow. And China’s determined, after all, to undermine American encirclement in East Asia by American allies and bases. So they are going to remain determined to increase their capabilities. So then we all ask this question: As the gap narrows, will conflict necessarily increase? And should we be concerned about the prospect for hostilities?

In some ways, I’m fairly optimistic that we can avoid that. After all, for the United States, this is not the Western hemisphere. America doesn’t need hegemony in East Asia in order to be secure. America’s still going to be a great power in the Indian Ocean, the Western Pacific. So that the rise of China in sharing power in East Asia is not something that America will feel it has to risk a great power conflict over. We’re trying right now to maintain that dominance, but I don’t think we feel it’s critical.

I think for many Americans, the issue is: America must lead. Which of course is not something that is necessary for security. I think if you push the issue and say, “Is it necessary that America leads for American security?” Then you get a lot more dour over whether it’s necessary. And I think that helps America to eventually accommodate itself to a shared leadership in East Asia.

Chow: So you’re optimistic about that.

Ross: I am. I always worry about unintended hostilities. Of course we worry in the South China Sea, whether or not the Philippines and China will exercise restraint. We worry in the South China Sea, where the American navy and the Chinese navy might have unintended collision. We worry in the Taiwan Strait, whether a Taiwan politician might provoke. And imagine those crises can be difficult in the context of our power transition. But I don’t see conflicts of interest out there that require increased hostilities. I see countries unable to back down. I see crises I can’t manage. That’s a very different process and different dynamic. And in those cases, we just hope that our leaders maintain control over their militaries, maintain leadership so as to manage this, so as to avoid escalation.

Singapore’s role in a rapidly changing world

Chow: Do you have some advice for small nations like Singapore? In such an era of flux and so many uncertainties?

Ross: I think most countries in East Asia have managed the rise of China fairly well. Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand… these countries have managed to maintain defence cooperation with the United States while expanding defence cooperation with China. They managed to take advantage of the Chinese economy in Chinese investment, while maintaining cooperation with the US economy. That’s a big change. After all, ten, 15 years ago, there was no cooperation on military exercises or arms sales with China and now there is. I think that’s the challenge: it’s how you begin to move toward cooperation with China without undermining cooperation with the United States. Most countries in the region have managed to do that well. I think the leadership in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and Thailand deserve credit for managing that well.

When of course you see other countries that are less successful. Let’s just say they’re flip-flopping. Every time we get a new leadership in the Philippines, from Arroyo to Aquino to Duterte to Marcos, the policy changes back and forth between the United States and China. Of course, we see that in South Korea. The Moon government was cooperating more with China. Now the Yoon government is cooperating more with the United States. That instability in their policies.

And of course from Taiwan as well. They had the Ma Ying-jeou administration, and then we had the Tsai Ing-wen. Again, flip-flops. It just shows you how hard it is for countries to manage this transition when you’ve been relying on the United States, cooperating with the United States for 50, 60, 70 years, and all of a sudden you need to find a way to cooperate less with America and find a way to cooperate more with China. That’s just very difficult. And now these countries that I have just mentioned have a very difficult time because public opinion matters, elections matter, and leadership often come from outside the political system. Or that certainly was the case in Korea, where we have a businessman running the country. Or the case in America — Donald Trump is running the country. And when that happens, the leaders come in with very little understanding of why policy…the way it is the way it is, and they will do a 180 turn. So you get these flip-flops.

So this is why we worry the most about Taiwan and the Philippines. And no one is particularly worried about Malaysia or Singapore or Indonesia because it’s pretty stable and well managed, even regarding the territorial disputes. So no one worries about Malaysia and China having escalated conflict over the Spratly Islands. It could be well managed. Same thing with Vietnam and China. It’s worth saying that China has never demanded that the other claimants to these islands accept China’s claim. China’s always insisted to “not challenge China’s claim”. Take this issue, put it aside, and let’s move on. Well, that’s what Vietnam has done. That’s what Malaysia’s done. That’s what Philippines did under Duterte, right? These are manageable problems that I think most countries have managed well. Going forward, I think we can still manage them well, and we’ll just wait to see how, particularly the Philippines, can adjust to the rise of China.

Chow: And in countries like Singapore and quite a number of Southeast Asian countries, have always been talking about not taking sides between China and the US. Do you think this is something that these countries can still continue to maintain moving forward?

Ross: So ten years ago, Singapore didn’t say… 15 years ago, Singapore didn’t say, “We’re not taking sides.” Now they say, “We don’t want to take sides.” That reflects the rise of China, as these countries try and manage both sides. I think many observers look at the Cold War, and they think, you know, whether we go back to the Cold War or whether we go back to blocs. That will not be possible for Singapore to avoid taking sides, or Malaysia — you’ll have to join a bloc. I think that misunderstands great power politics, it misunderstands East Asia. Now the Cold War was unique in that these two blocs in Europe had an iron curtain between them, and there was no cooperation. And both sides were so nervous about war that they had to just become polarised into their blocs. Asia’s not like that. No one is worried about a Chinese invasion across the South China Sea into Malaysia. So you can have greater flexibility in your foreign policies without being so worried about war as European countries were.

The Soviet Union didn’t have an open economy; China does. So the idea of not having economic cooperation between two blocs is also not going to happen. I think going forward, you’re going to see a very fluid region. You’re going to see military, naval exercises between the United States and Singapore, China and Singapore. Philippines will have them with both eventually, I think. Malaysia similarly. Indonesia. It’s far healthier than the Cold War, where there’s greater fluidity without the blocs, with trade across countries, between Singapore and the United States, Singapore and China, and there’s no reason that should end. That should be the future.

I don’t see the US-China relationship undermining the autonomy, the independence of Singapore and the ASEAN countries. — Ross

Chow: So even with the uncertainties and unpredictability the Donald Trump administration is bringing to the world, you are actually pretty optimistic about how things will turn out in the end.

Ross: Well, I think we do need to worry about how Donald Trump will influence the global order. We already see the implications of the American trade war spreading to other countries, as Chinese exports are no longer going to the United States, they’re flooding other countries, then those countries are putting up trade restrictions. And so you begin to see protectionism spreading around the world. Turkey, Brazil, other places. Europe you see it too. So if America and China cannot manage their economies, you could see protectionism going global. And that would be very costly for the entire world.

I would also worry about Donald Trump and what it means for the security of NATO countries, and for American foreign policy as we burn our bridges to our allies. And I would also worry about the implications for the United States of an inability to manage US-China relations. But as I look at Asia, no matter where the US-China competition goes, in South China Sea in particular, I think the region itself has the ingredients for stability and moderation. Of course, we worry about accidents. But I don’t see the US-China relationship undermining the autonomy, the independence of Singapore and the ASEAN countries.