China will shake the world: Success recipe (Part I)

In this two-part article, we explore China's progress from a poor, underdeveloped country to an economic superpower, with a major impact on world affairs. How has this been possible? What does it mean for the rest of the world?

For centuries, China exerted a cultural attraction and was, together with India, a leading player on the world stage. After a century of harrowing colonization, humiliation and internal civil wars, Mao Zedong put his country back on the world map in 1949.

It was the start of a 'development marathon at a great pace' that would shake up global relations. And as Napoleon Bonaparte predicted earlier: "China is a sleeping giant. When it awakens, the whole world will shake".

From trial and error to economic miracle

At the time of the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the country was one of the poorest and most backward in the world. The vast majority of the Chinese were employed in (often primitive) agriculture. Per capita GDP was half that of Africa and one-sixth that of Latin America. To give the revolutionary ideals of equality a chance in a highly hostile world environment, it was necessary to achieve rapid economic and technological growth. This was to take place over the next 70 years through a process of trial and error.

In comparison with Western Europe, China's industrialisation went four times as fast, and with a population five times as large.

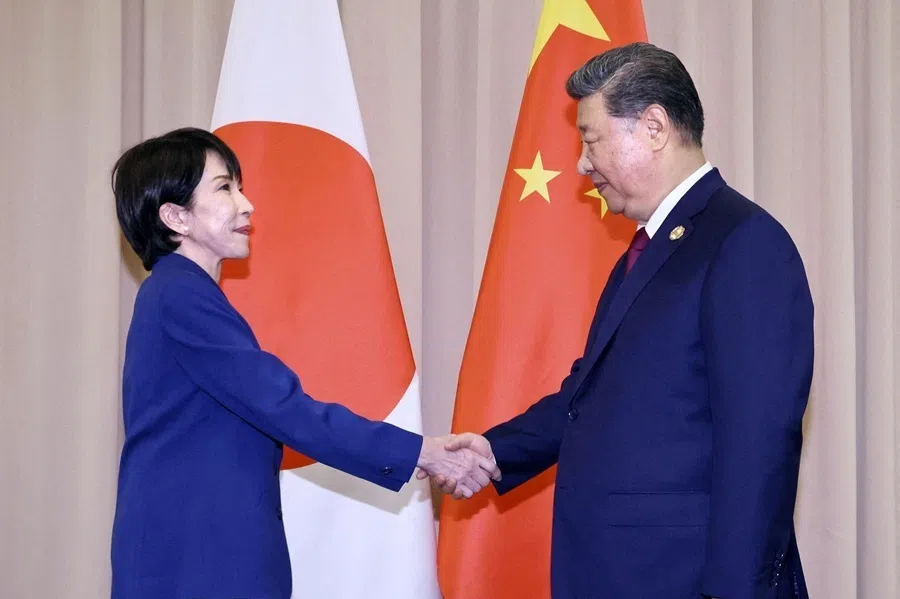

After an extremely introverted and turbulent period under Mao Zedong-in which controversial mass campaigns were launched such as 'The Great Leap Forward' and 'The Cultural Revolution'-Deng Xiaoping took up the torch in 1978. Almost immediately but cautiously, he launched economic reforms and established relations with numerous countries, including, remarkably, the United States.

Until recently, China was seen as an imitator of technology. Today, it is a leading innovator.

In comparison with Western Europe, China's industrialisation went four times as fast, and with a population five times as large (end note 1). Seventy years ago, the Chinese economy was insignificant. In 2014, the Chinese surpassed the US as the largest economy (in terms of volume) and it also became the largest exporting country. Today there are 35 Chinese cities with a GDP equal to that of countries such as Norway, Switzerland or Angola. The Chinese GDP has meanwhile become larger than the combined GDP of 154 countries.

In 2011-2012, China produced more cement than the US during the entire twentieth century. It built ten new airports each year and has the world's most extensive network of motorways and high-speed train lines. At present, the country exports as much in six hours as it did in 1978 on an annual basis.

Technological leap forward

China is not only surprising in terms of quantitative evolution. In terms of quality, the Chinese economy has also made huge leaps forward, technological development is the prime example. Millions of engineers, scientists and technicians have graduated from Chinese universities in recent decades. Until recently, China was seen as an imitator of technology. Today, it is a leading innovator. China currently has the fastest supercomputer and is building the world's most advanced research center to develop even faster quantum computers.

Does China owe part of its technological progress to the stealing of intellectual property? Undoubtedly, as is the case with countries such as Brazil, India and Mexico.

In recent years, the country has achieved impressive results in the field of hypersonic rockets, human gene processing tests, quantum satellites and perhaps most importantly: artificial intelligence. The Made in China 2025 project aims to strengthen that technological innovation in vital socio-economic sectors.

Does China owe part of its technological progress to the stealing of intellectual property? Undoubtedly, as is the case with countries such as Brazil, India and Mexico. In the past, the US, too, has only been able to develop its economic growth at the level of superpower thanks to the large-scale theft of technology from Great Britain and Europe. As The Economist puts it, "The transfer of know-how from rich countries to poorer ones, by hook or crook, is an integral part of economic development."

Recipe for success

The success of the Chinese modernisation sprint is based on various pillars:

The key sectors of the economy are in the hands of the government, which also indirectly controls most of the other sectors, inter alia through the controlling presence of the Communist Party in most medium-sized and large companies.

The financial sector is under strict government control.

The economy is planned, not in all details but in general, both in the short term and in the longer term.

There is room for private initiative within a well-delineated market mechanism that is dynamically developed in various economic domains; the market mechanism is tolerated as long as it does not interfere with economic and social objectives (of the overall planning).

Compared to other emerging countries, there is a high degree of openness to foreign investment and foreign trade, provided that it is in line with China's global economic objectives.

A great deal of effort is being put into developing infrastructure and Research & Development.

Wages largely follow the increase in productivity, which has created a large and dynamic internal market.

A relatively large amount is invested in education, health care and social security.

The country has enjoyed peace for decades and there is a relatively high level of social peace in the workplace.

The distribution of agricultural land to farmers at the start of the revolution and the system of individual household registration (hukou) have made it relatively possible to avoid the typical chaotic rural exodus of most Third World countries, resulting in massive informal and unproductive work.

Unlike the Soviet Union, China has not embarked on a very expensive arms race with the US.

The key sectors of the economy are in the hands of the government, which also indirectly controls most of the other sectors, inter alia through the controlling presence of the Communist Party in most medium-sized and large companies.

The financial sector is under strict government control.

The economy is planned, not in all details but in general, both in the short term and in the longer term.

There is room for private initiative within a well-delineated market mechanism that is dynamically developed in various economic domains; the market mechanism is tolerated as long as it does not interfere with economic and social objectives (of the overall planning).

Compared to other emerging countries, there is a high degree of openness to foreign investment and foreign trade, provided that it is in line with China's global economic objectives.

A great deal of effort is being put into developing infrastructure and Research & Development.

Wages largely follow the increase in productivity, which has created a large and dynamic internal market.

A relatively large amount is invested in education, health care and social security.

The country has enjoyed peace for decades and there is a relatively high level of social peace in the workplace.

The distribution of agricultural land to farmers at the start of the revolution and the system of individual household registration (hukou) have made it relatively possible to avoid the typical chaotic rural exodus of most Third World countries, resulting in massive informal and unproductive work.

Unlike the Soviet Union, China has not embarked on a very expensive arms race with the US.

This approach contrasts with the recipe of capitalist countries where financial capital and multinationals are in charge, short-term profit is the overriding goal, and governments are fixated on eliminating budget deficits through savings. The spectacular way in which they have tackled the financial crisis (2008) is typical of China. The Chinese government launched a stimulus program at 12.5% of GDP, probably the largest peacetime program ever. The Chinese economy plummeted a little but then picked up quickly, while the European economy has been teetering during the ten years.

Domestic market as driving force

Due to rapid changes in the internal labor market, wages and foreign markets, the Chinese government developed a different growth model. When President Xi Jinping took office in 2012, he stated that 'growth for growth's sake' should no longer be the goal. The old model was based on exports and investments in construction, manufacturing and heavy industries. In the new model, the driving force is mass consumption (domestic market), the service sector and high added-value activities up the technological ladder. This transformation illustrates the flexibility in which the Chinese leadership implements economic policy. It is the 12th pillar of the Chinese recipe. This flexibility stands out from the way the Soviet Union dealt with these challenges in its later period.

Is this successful growth sustainable? Without a doubt, the economy is struggling with a huge debt, shadow banks, overinvestment in infrastructure, a real estate bubble, an ageing population, a tension-ridden trade war with the US, and so on. Yet, most observers still see China as a resilient economy. Analyses show China still has substantial room for error and setbacks, and a huge potential for rapid growth in the long run.

The greatest leap to overcome poverty in history

In 1949, the Chinese had a life expectancy of 35 years. Thirty years on, it doubled to 68 years. Today, the life expectancy of the Chinese is 76 years. Infant mortality has improved fairly well. If, for example, India offered the same medical care and social support to its inhabitants as China does, 830,000 fewer Indian babies would die each year (end note 2).

Between 1990 and 2013 China succeeded in lifting a record number of people out of extreme poverty: 635 million. This amounts to the total population of sub-Saharan Africa during that period. At the current pace, extreme poverty will be eradicated by 2020. According to Robert Zoellick, former President of the World Bank, this is "certainly the greatest leap to overcome poverty in history. China's efforts alone have ensured that the world's Millennium Development Goal on poverty reduction will be met. We and the world have much to learn from this."

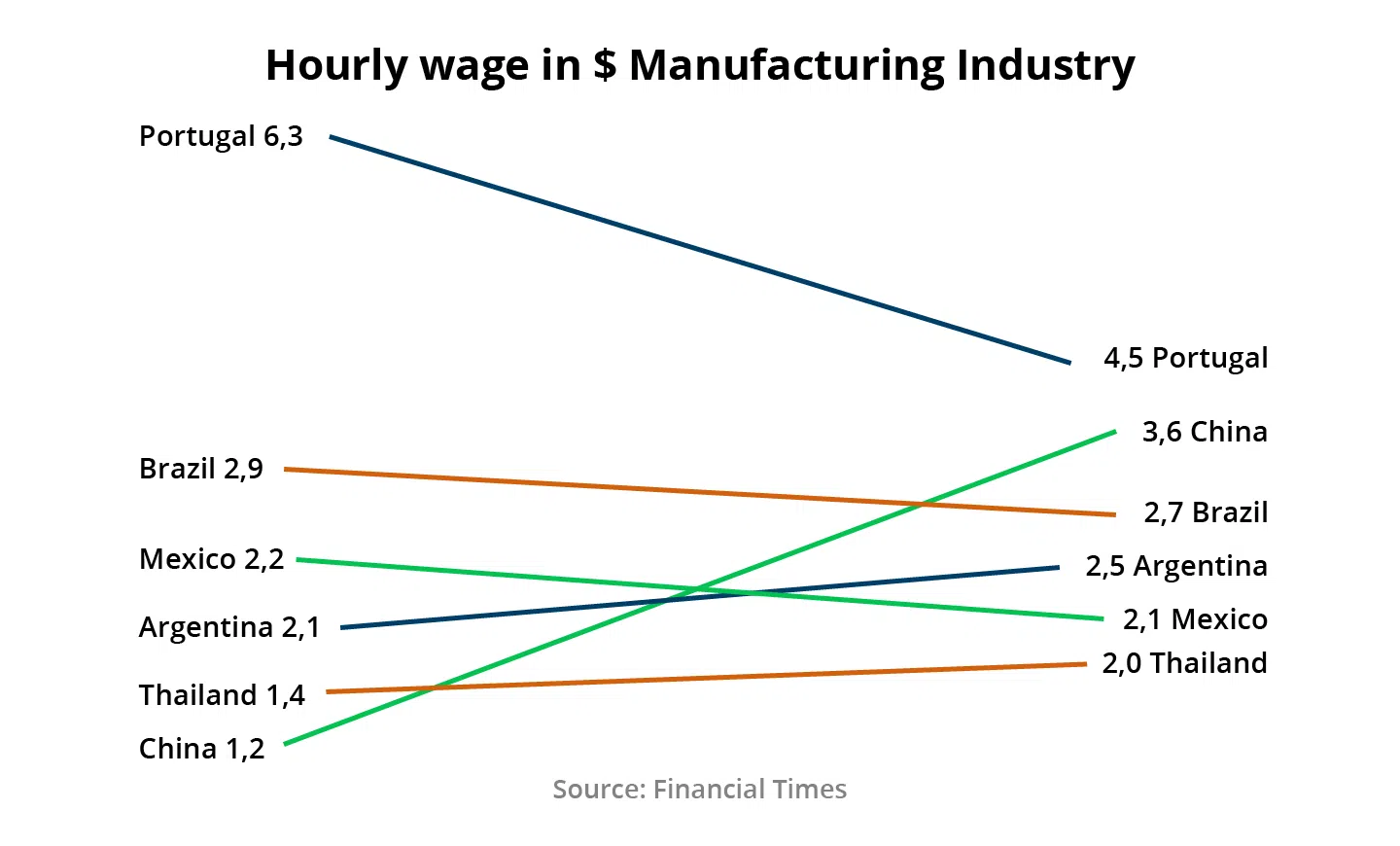

While wages are stagnating or declining in many countries, they have tripled in China over the last decade. Fifteen years ago, Western multinationals flocked to China because of low wages. The reverse movement is now starting to take hold. The average wages in the Chinese industry are currently only 20 percent lower than in Portugal. Countries such as Bulgaria, Macedonia, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine already had lower minimum wages in 2013 than in China.

Economic, social and gender issues

This success story also has its drawbacks. The faster increase in productivity in industry and services, compared to agriculture, has led to a big gap between urban and rural areas, between poorer regions and the richer eastern coastal provinces. The strict hukou system (registration of the individual residence, determines the social status) results in a huge group (of hundreds of millions) of 'internal migrants' who have less social rights and are often being discriminated. The one-child policy (since 1978) has led-apart from its binding character-to numerous selective abortions and a male surplus of more than thirty million.

Is the Western system superior?

The West usually regards its own political system as a superior and authoritative model. This doesn't demonstrate much historical insight knowing that almost all fascist regimes were born in the womb of western parliamentary democracy. An unbiased observer will also observe that Western democracy mainly serves the interests of the 1%. It lacks both a long-term vision and an effective policy to tackle social and ecological problems. It has also produced ludicrous and unpredictable figures such as Trump, Johnson, Bolsonaro and Duterte.

In this respect, the Chinese attach more importance to the quality of their politicians than to the procedures for choosing their leaders.

When it comes to democracy, the emphasis in the West is on the input, it addresses the question of how and by whom decision-making takes place. What are the procedures for choosing the political leadership and is the will of the citizens voiced by the elected representatives? Elections are the most important element in this.

In China, the emphasis is on the output, i.e., on the consequences of the decision: is the decision successful and who benefits? The result is paramount, good and fair governance is the most important criterion. In this respect, the Chinese attach more importance to the quality of their politicians than to the procedures for choosing their leaders.

Chinese formula for governing a large country

According to Daniel Bell, an expert on the Chinese model, China's political system is a combination of meritocracy at the top, democracy at the base and room for experimentation at the intermediate levels. The political leaders are selected on the basis of their merits and, before they reach the top, they go through a severe process of training, practice and evaluation. There are direct elections at the municipal level and provincial party congress. Political, social or economic innovations are first tested on a smaller scale (a few cities or provinces) and after thorough evaluation and adjustment, implemented on a large scale. According to Daniel Bell, that combination "comes close to the best formula for governing a large country".

In addition, the central government organises opinion polls on a very regular basis which assess the government's performance in the areas of social security, public health, employment and the environment. The popularity of local leaders is also the subject of the surveys. Based on this, policies are frequently adjusted.

The Chinese decision-making system has proved its worth. Francis Fukuyama, who can hardly be suspected of left-wing or Chinese sympathies: "The most important strength of the Chinese political system is its ability to make large, complex decisions quickly, and to make them relatively well, at least in economic policy. China adapts quickly, making difficult decisions and implementing them effectively."

For example, in just two years, China has extended the pension system to 240 million rural residents, which drastically exceeds the total number of people covered by the US state pension system.

It should therefore come as no surprise that the Chinese government can count on great support from the population. Around 90 percent say their country is heading in the right direction. In Western Europe, that is between 12% and 37% (the global average).

Three-quarters support the one-party system

The backbone of the Chinese model is the Communist Party. With more than 90 million members, it is by far the largest political organisation in the world. The gigantic proportions of the country mean that this backbone is useful or even necessary.

China is the size of a continent: it is 17 times the size of France and has as many inhabitants as Western Europe, Eastern Europe, the Arab countries, Russia and Central Asia combined. Translating this into the European situation would mean that Egypt or Kyrgyzstan would have to be governed from Brussels. Given these proportions, the large differences between the regions and the huge challenges facing the country, a strong cohesion force is needed to keep the country governable and capable of implementing a solid policy. According to The Economist, "China's rulers believe the country cannot hold together without a one-party rule as firm as an emperor's (and they may be right)."

The party recruits the most skillful people. The selection process for promoting top leaders is rigorous. Kishore Mahbubani, an expert on Asia observes: "Far from being an arbitrary dictatorial system, the CPC may have succeeded in creating a rule-bound system that is strong and durable, not fragile and vulnerable. Even more impressive, this rule-bound system has thrown up possibly the best set of leaders that China could produce." Nearly three quarters of the population say they support the one-party system.

Figure: Marc Vandepitte and Ng Sauw Tjhoi. Reproduced by Jace Yip.

End note

We take 1870 as a starting year for Western Europe and 1980 for China. We measure the speed of the industrialization process based on the growth of GDP per capita. The figures are calculated on the basis of Maddison A., Ontwikkelingsfasen van het kapitalisme, Utrecht 1982, p. 20-21 en UNDP, Human Development Report 2005, p. 233 en 267. Zie ook The Economist, 5 januari 2013, p. 48.

Calculated on the basis of UNICEF, The State Of The World's Children 2017, New York, p. 154-155.